3/8

COLLOQUIALISING ARABIC LITERATURE

by Marcia Lynx Qualey

The use of colloquial Arabic in Egyptian literature has become more and more popular, even though Modern Standard Arabic is still considered the serious way to go. This is the story of how Egypt is leading the way with this new trend of publishing in colloquial.

Battles over language are common across the twenty-some countries where Arabic is in regular use. The dubbing of a recent Disney film in Modern Standard Arabic (MSA) sparked weeks of debate. Meanwhile, in Algeria and Morocco, there has been fierce resistance to suggestions that students be taught their first primary years in Darija, a dominant spoken dialect. In the Emirates and Lebanon, there are regular cries that Arabic is dying.

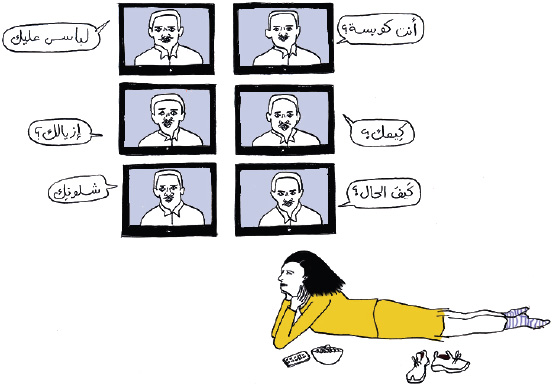

MSA has long been the formal language of writing and media, shared across Arab countries and beyond. Colloquial Arabics are local, overlapping, and sometimes mutually unintelligible. This is not always the case: many Arabs can understand Egyptian because of the long-time dominance of Egyptian films, and Levantine Arabic because of newer Syrian films or Lebanese songs. However, the Egyptian travelling to Algiers cannot expect to communicate in the local spoken Arabic; in all likelihood, she would also give up on a Darija novel.

Over thousands of years of diglossia, colloquial Arabics and MSA have taken over different domains. Colloquials have become languages of kitchen, home, cursing and ordinary life, while MSA has occupied the ground of politics and philosophy. So writers and poets are faced with a question: In which of these should literature be written?

In the mid-20th century, Egyptian short-story writer Yusuf Idris shattered the existing tradition when he began writing dialogue in colloquial, by now a common practice. In 1966, Egyptian novelist Mustafa Musharafa published what’s thought to be the first modern novel completely in colloquial Arabic, Qantara Alladhi Kafara (“Qantara Who Disbelieved”).

For the most part, others didn’t follow. There are novels that oscillate between the languages – to mixed critical reception. Egyptian novelist Ahmed Alaidy’s Being Abbas El Abd was both praised and accused of “intellectual impoverishment” for mixing too much vulgar, ordinary language in with his MSA. Youssef Rakha’s The Sultan’s Seal code-switched in a way that could be likened to Junot Díaz’s The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao, where Díaz flips between different registers of English and Spanish. It was beloved by fellow writers but ignored on the prize circuit, its experimentations with language taking it perhaps a bit too far from the judges’ conservative literary expectations.

The colloquial-only novel

Blogs, meanwhile, offer a new space where writing in “vulgar” colloquial, or ‘ameya, is welcome. When Egyptian pharmacist and aspiring writer Ghada Abdel Aal launched her popular blog, Ayza Atgowaz (“I Want to Get Married”), she didn’t debate her choice of language. To achieve the intimacy and humour of a first-person narrative, she had to write as though she were speaking.

Abdel Aal used her blog to make witty observations on the process of meeting, or failing to meet, a future spouse. Later, when Abdel Aal shaped her blog posts into a popular novel of the same name, she also crafted it in colloquial Egyptian Arabic. She said she has “never” considered translating herself into MSA.

Writing the blog and book, she says, “was like talking to your friends in a gathering, which is never done in fos’ha [MSA].”

This sort of intimate chatter has “become exclusive to ‘ameya,” says Jordanian novelist Ma‘n Abu Taleb. “Whilst anything complex or intellectual is exclusive to fos’ha. There is almost no overlap between those two spheres of language, and therefore, thought. This means that intellectual ideas and discourses don’t cross over from academia and books into daily life. It also means that everything expressed in fos’ha is idealistic, detached from life, and is oblivious to the real world.”

This creates a potential crisis in the novel, particularly for authors who want to use an intimate, first-person narrative. Many authors have steered away from first person, or even – like Palestinian writer Adania Shibli – from dialogue. For the most part, writing in ‘ameya remains an unpopular choice for “serious” literary novelists. Some, like scholar Elias Muhanna, have suggested the distancing effect of MSA is why Arabic-speaking children don’t easily pick up reading, because it’s harder to emotionally engage the text.

Muhanna has likened the language used in an MSA children’s book about going to the doctor to English that sounds like: “Forsooth didst the nayward damsel alight upon the threshold of the quacksalver’s vestibule … A panic came upon her ‘ere [sic] her mother didst coax her forward, dreading the prick of the misprised instrument…”

Yet the educated sector spends years steeped in MSA, and it becomes natural to see this as the only way to write. Egyptian writer and economist Galal Amin, who chaired judging for the 2013 International Prize for Arabic Fiction, said in an interview that the committee received only one work written in colloquial that year. “You can produce something exceedingly beautiful and appealing and useful by using ‘ameya. But also ‘ameya could be terribly low and vulgar and does not achieve what a good literary work should. So we have to be very careful.”

This argument of lowness and vulgarity has also faced colloquial poets, Abdel Aal says.

“They faced it and proved themselves. I don’t see why we are always describing colloquial as a low form of Arabic. Why shouldn’t I choose the same form of Arabic that I think in to write down my ideas? No one, as far as I know, thinks in fos’ha! … I’m not saying that everybody should use it, but it should be regarded as serious, just like fos’ha".

For many Arab authors outside Egypt, colloquial has remained off limits. When acclaimed Lebanese author Fatima Sharafeddine first began writing books for children, she wanted to use Lebanese colloquial. But she was told by publishers that they couldn’t sell enough copies that way. The Goethe-Institut has run several children’s-literature writing workshops in the United Arab Emirates where it was acceptable to discuss dialogue in ‘ameya, but writing an entire children’s book that way was nearly a taboo.

The ‘serious’ writer

Arabic’s literary novelists have generally shied away from using too much colloquial. In a 2009 conversation at London’s Frontline Club, Egyptian novelist Bahaa Taher said that experimentations with colloquial made sense in Yusuf Idris’ day, but authors who currently write in it are “not mastering their own language.” By “writing in slang they are defeating themselves.” But at the same event, Lebanese novelist Elias Khoury disagreed. The use of colloquial, he said, was something “we can learn from the Egyptian novel actually."

Yet those who write a book fully in colloquial are generally taken less seriously.

Enas Haleem, unlike Abdel Aal, wrote two books in MSA before publishing her collection of linked short stories, Taht El-Sireer (“Under the Bed”), in colloquial. “I see [colloquial] as one type of writing,” Haleem says. Whether an author uses the vernacular or not, she says, depends on the “target of the experiment and the area the writer wants to cover.”

A market for colloquial novels – at least for adult readers – has developed in Egypt. Still, most of the contemporary Egyptian books written in colloquial are lighter social commentary and satire. Abdel Aal thinks these books are particularly suited to being written in the vernacular. “But I personally would read any book in any genre or about any subject written in colloquial, as long as it is well-written.”

The colloquial can offer the writer new avenues for humour, but it can also do other things, such as create a closeness to the narrator. “I could never be as funny using fos’ha,” Abdel Aal says. But the colloquial has other uses: It gives her a fresh intimacy with the reader, she says, a closer first-person effect. “With colloquial the reader feels strongly that I write in his voice, I understand him, I know what he is going through. With colloquial, you are closer to his thoughts and dreams.”

But “writing in the colloquial is not as easy as most writers or some readers think,” Haleem says. The vernacular is not just for light writing, but can express “very serious things and important feelings and details.” She points to Salah Jahin and Ahmed Fouad Negm, two popular colloquial poets who have addressed many areas of Egyptian life.

“If you choose to write in colloquial,” she says, it’s not like an untamed stream of consciousness. “You still need to maintain the cohesion of the text.”

Some authors who’ve used Egyptian colloquial, such as Safaa Abdelmenem, point to Musharafa’s pioneering Qantara Who Disbelieved as an inspiration. But Haleem says that Ahmed El-Fakharany’s Fi Kull Qalb Hikayah (“In Every Heart There Is a Story”) was the door that opened colloquial to her, helping her realise that the vernacular could be used in serious literature.

“Writing in colloquial helped me to integrate the small details of the characters’ lives and to express them more simply. It also removed some of the lukewarm barriers that are imposed sometimes by fos’ha,” Haleem says. “Writing in colloquial is close to my heart because it looks at the character’s internal situation and the internal rhythm of human souls.”

Abu Taleb, whose first novel will come out this year, suggested that ‘ameya might be the only way to do a first-person, stream-of-consciousness novel in Arabic. Rakha has shown that the delight in linguistic registers can make a novel cohere, while Abdel Aal and others have shown that ‘ameya can bring in new readers. Arabic’s diglossia – while in some ways a hurdle – also presents rich ground for fresh experimentation.