Mental health, a political issue in the Arab world

Translated from French by Noël Burch

This dossier was produced as part of the activities of the Independent Media Network on the Arab World. This regional cooperation brings together Maghreb Emergent, Assafir Al-Arabi, Mada Masr, Babelmed, Mashallah News, Nawaat, 7iber and Orient XXI.

According to the World Health Organisation (WHO), one person in eight lives with mental health issues, especially one of the anxious or depressive types. This situation has worsened since 2020 and the Covid-19 pandemic. But if the whole world is crazy, isn’t it only normal that we ourselves are too? While many psychological issues are biological and genetic, many also have underlying environmental stressors, be they familial, socio-economic, or political. These environmental issues may also aggravate pre-existing disorders.

In the Arab world, the prevalence of mental health issues is higher than the global average, with an average of 29 percent dealing with depression. The number is highest among people from Iraq, Tunisia, and Palestine, but still significantly high among Moroccans and Algerians (20 percent). In addition, the ongoing genocide in Gaza and the images coming from there has had an even bigger psychological impact, especially through the accumulation of feelings of anger and injustice.

The region is full of potential causes for mental health disorders to emerge and aggravate, and many are of a political nature. A certain number of countries remain the prey of unending conflicts (Palestine, Syria, Yemen, Iraq) which is traumatising generations of people. This also holds true for Lebanon and Algeria, after their civil wars and the lack of proper closures. Massive population displacements, as in Sudan, also increase the risk of impact on people’s mental wellbeing.

In view of the increased authoritarianism since the Arab revolts of 2011, political disillusionment, like in Egypt and Tunisia, has morphed into apathy and a feeling of powerlessness. Added to this are the deteriorating economic crises, the demographic growth, and skyrocketing urbanisation which all overburden existing healthcare infrastructures. All of these have gravely worsened the anxiety and depressive disorders among the population, which are not properly treated.

While individualism might remain less pronounced in the Arab world than in some other places, thanks to strong familial ties and group solidarity, the massive use of social media platforms in the region is furthering a virtual vision of the world, inevitably posing a threat to mental health. Women’s place in society and the global patriarchal system is another factor. As psychiatrist Nawal El Saadawi said in an interview: “The ordinary Egyptian woman is the slave of men, the slave of society, of religion and of the political-economic system which weighs heavily on us all.” This could result in an increase in suicidal behaviours, like in Iraq, where the suicide rate has doubled in five years. The consumption of psychotropics is also on the rise, as in Tunisia, where it is difficult to keep track of doses and duration of treatments, which may constitute a danger in itself.

So long as the infrastructures and quality of healthcare remain lacking in the region, mental health will remain the poor cousin of medicine (even as the situation differs from country to country). In 2012, a study carried out despite the difficulties in accessing data showed that there were many inadequacies in terms of legislation, available hospital beds, and trained specialists in the Arab world. This is what this dossier concludes as well, especially when it comes to overall healthcare policies, difficulties in accessing treatment, and geographical disparities. And this in spite of the World Health Organisation’s observation that every dollar invested in treating mental health disorders will yield five dollars, through improved health nationwide and gains in productivity.

This regional situation, worsened by the continual departure of mental health specialists abroad, foreshadows the development of alternative medications—through religion or personal development trends—which widens the gap between patients and the medical establishment. The topic of mental health in general remains taboo. A survey from 2020 showed that nearly 50 percent of youth in the Arab world saw mental health as something viewed negatively in their country.

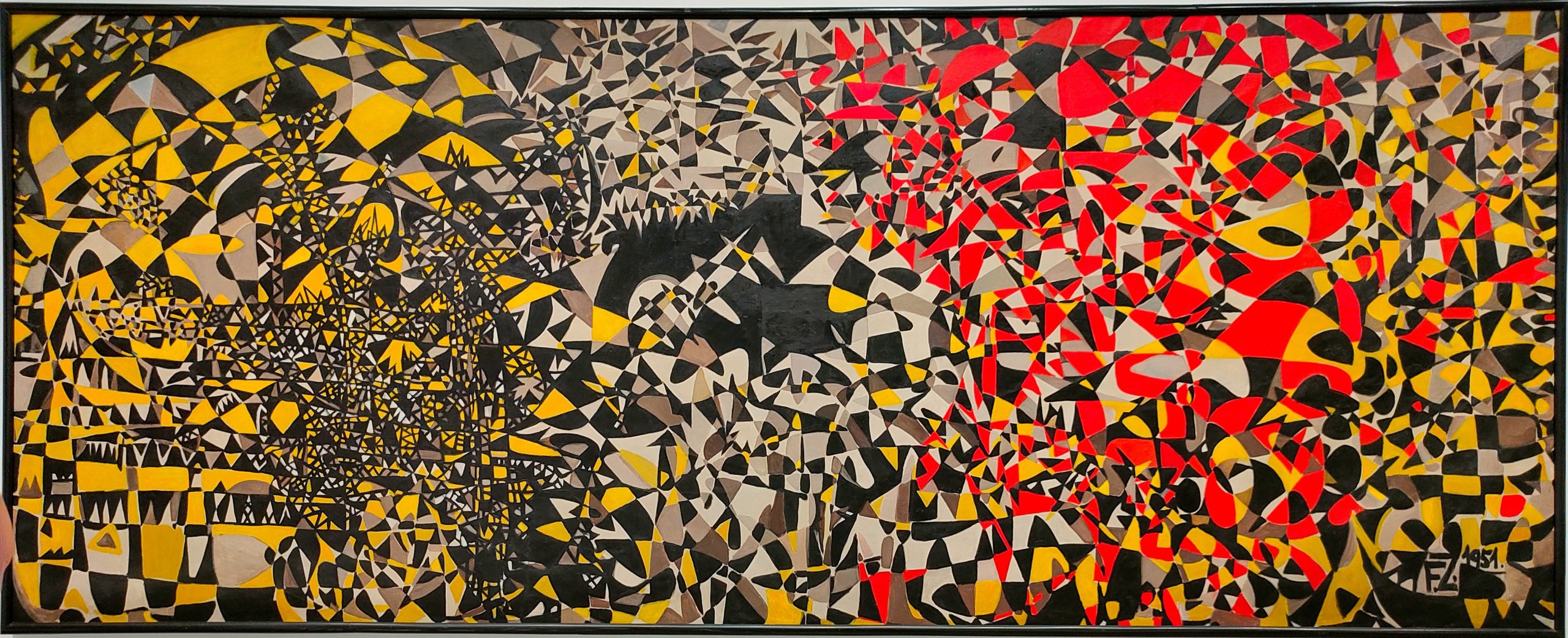

The issue of mental health issues, including how to try and treat them, is a political one too. Franz Fanon understood this, when he claimed that social change went hand in hand with the psychological liberation of individuals. In a political context as hectic as our current one, caring for psychiatric disorders should be something that links individual clinical treatments with broader policies, where the collective social and political factors behind these individual symptoms are recognised.

In light of all of this, the Independent Media In the Arab World network has decided to devote a series of articles to the topic of mental health. Not only because these observations remain pertinent and politically and socially important, but also since it is difficult to access statistics and the media coverage of mental health issues remains poor.

In his article for Asafir Al-Arabi, entitled “Mental health in Iraq is growing steadily worse,” Mizar Kemal notes that the funds devoted to mental health in Iraq are less than 2 percent of the total healthcare budget, and that only three psychiatric hospitals serve a population of 43 million. In a country which has experienced four major wars, an embargo, and several civil wars in the last four decades, the psychological impact has been disastrous. Among the consequences are a rise in the number of suicides and the consumption of psychotropics—Metamphetamine and Captagon.

In their article for Babelmed, “Treating mental illness in Algeria,” Ghada Hamrouch and Ghania Khelifa manage to discuss the issue of the decline of mental health in Algeria despite the lack of available statistics. They speak about “a population caught between two traumatic events, the war of liberation on the one hand and a civil war on the other.” Despite the existence of a number of specialists and care facilities which can be described as “acceptable,” there are inadequacies in the quality of care and the access to treatment, and disparities on a regional level.

In her article for Nawaat, “Anxio-depressive disorders: Tunisians at the end of their tether,” Rihab Boukhayatia shows that these disorders have grown significantly more frequent. Tunisia ranks 115th out of 143 countries on the World Happiness Index, scoring low on the indicators of the feeling of being free, the absence of corruption, the level of earnings, and social support. The author covers the harmful influence of social networks and the growth of the so-called “happiness industry.” She also speaks about the growth of drug use since 2013 as “a form of self-medication,” as well as the consumption of anxiolytics, especially among teenage girls.

In her article for Mashallah News, “The struggle for mental health in Lebanon’s crisis,” Layla Yammine links the impact of poverty—which tripled in six years according to the World Bank—on mental health issues and treatment. The high cost of treatment, in a largely privatised medical system, means that it is not available to everyone. Despite national strategies designed to modernise the sector, in 2020, only 5 percent of all governmental health expenditures went to mental health care. Specialists leaving the country, self-medication, stigmatisation, and taboo all coincide with past and current traumatic events. The explosion in Beirut’s port on August 4, 2020, the financial collapse, and now Israel’s war on Gaza and South Lebanon have all heightened feelings of fear, anguish, and anxiety in Lebanon’s population.

In his article for OrientXXI “Mental health in Morocco, a road strewn with stumbling blocks and atrocities,” Mohammed Al-Nejjari reminds us that nearly half the Moroccan population suffers from psychological disorders. The lack of public policies, adequate reception capacities, and treatment structures make it impossible to cope with the problem, all the more so as there is less than one specialist for 100,000 inhabitants. The lack of available care gives rise to bribery and nepotism, and many patients turn to the lucrative market of alternative practices, including visits to sanctuaries such as the Bouya Omar mausoleum, known to people as Guantanamo, which was shut down in 2015, and ruqya sessions.

Mahmoud Bashir, in his article for Mada Masr, shows that mental health issues in Gaza have been made much worse by the ongoing war, not to speak about the acute absence of absolutely basic and life-saving necessities such as food, water, shelter, and medicine. He also looks at the massive destruction wreaked on medical infrastructures in Gaza, where even before October 7 psychological treatment was acutely lacking.

Finally, in her article for 7iber, Abeer Juan looks at the differences between medicine and other therapeutic approaches in psychiatric treatments in Jordan, where 20 percent of the population is thought to be dealing with depression and anxiety.. Medicine is the dominant treatment for several reasons, the author says, that are linked to a lack of specialised medical personnel and public financing, as well as the weight of administrative tasks and a general lack of mental health considerations.