Graffiti without a cause

The Kingdom codes

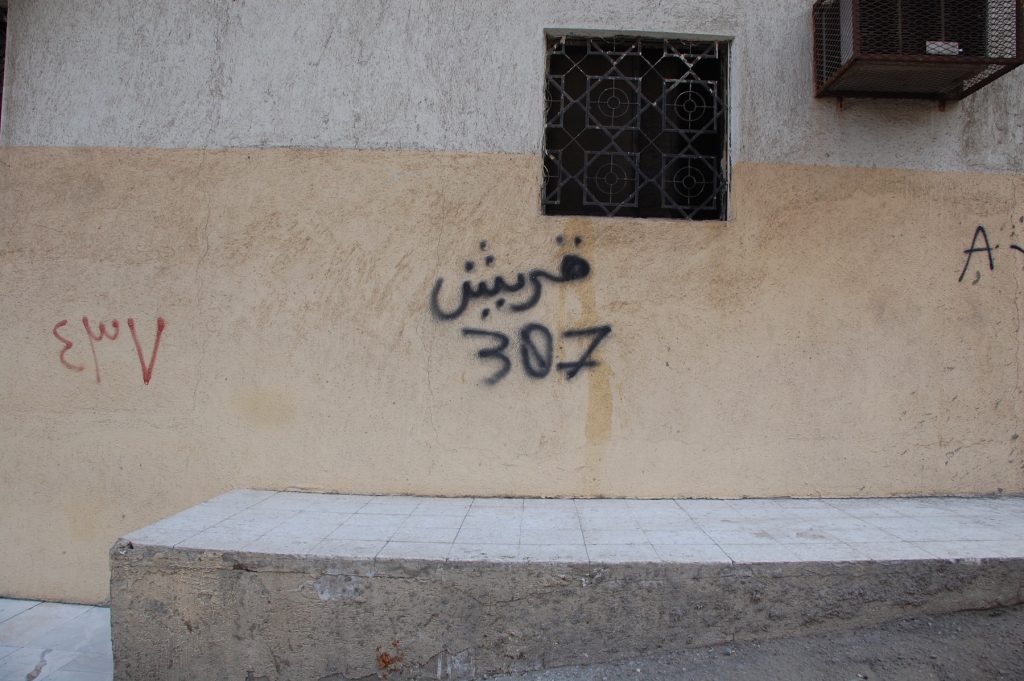

911, F-16, 666. Numbers that seem to signify danger, alarm. War, maybe. But in this coding system in Saudi Arabia, they are graffiti tags representing tribes and regions. 305 for al-Mutairi, 505 for al-Qahtani and 511 for al-Otaibi, or 07 for “the south”.

It is difficult to describe the graffiti and street art scene in the Saudi kingdom, a country with large urban spaces far away and detached from one another. What you find in Jeddah’s artsy historical city al-Balad is unique from what is trending nationally, and the politicized walls of Qatif display the town’s own culture in a similar way to what you see on the walls of Bahraini villages. But there is one graffiti phenomenon worth noting – one that seems to transcend ghettos, big cities, and even suburban towns.

When graffitited on today’s walls, these numerals stand to signify pride. “I am here”, “I am from here”.

On walls across the kingdom, the country’s mounting and marginalized youths, intoxicated with indifference, become visible. We get to know their phone numbers and BB pins, and how they immerse themselves into the electronic modes of communication. We also get to know something else, deriving from a past and not an assimilated modernity: their attachment to old tribal affiliations, signified by three-digit codes.

If we try to trace these numbers, we find some sources claiming that their origins are an old tradition of camel branding, where camels would be tattooed with numbers and symbols of the different tribes. Other sources say instead that they simply refer to area codes (like 07 for the south); it’s complicated and the documentation is vague, but it seems likely that the camel branding evolved into these numeral codes. One such example is the Otaibi tribe, which had a code that looked like (حلقة و مطرقتين), and evolved into the number “511”.

In any case, whatever the number or name, when graffitited on today’s walls, these numerals stand to signify pride. “I am here”, “I am from here”. Similar, in its essence, to the kind of tagging seen on walls in other cities across the globe.

In Saudi Arabia, they can be found on walls all over the country. Like “غامد والقلب جامد”, which means “Ghamid and the heart is solid” (Ghamid is derived from the family name Ghamdy); “وخر عن دربي تراني حربي”, which means “Move away from my pathway, for I am Harby”; or “مطيري وأكيد أحسن من غيري”, which means “Mutairi, and no doubt better than others”.

These slogans, which rhyme in colloquial dialect, are indications of the continuous strength and pride of the different tribes. The tags are much more common in the country than artistic street art, yet still, they have not yet been documented as a graffiti phenomena. More conventional street art has gotten much more coverage from both local and foreign journalists, though in actuality, it remains a rarity. Not like what you get used to see in Beirut or Cairo. What we are used to, in Jeddah, Riyadh and elsewhere, are these numbers and slogans.

The sense of pride that these tribal tags represent is not something expressed solely by a fraction of the youth. It extends to a wider contemporary urban phenomenon, known as hajwalah. The term is used for a Saudi subculture, engaged in public space activities ranging from drifting to vandalism and mirroring a rebellious attitude among emotionally confused young people, struggling to find meaning in their lives. Hajwalah has become an alternative escape from heavy social and religious restrictions; a solution to boredom and lack of engagement with the rest of society. As young people meet and spend their time together in the city and its outskirts (drifting, doing other dangerous motorsport activities), they also tag the walls, engraving their name and place into the public space. The graffiti ranges from their name tags and nicknames to jokes, song lyrics, phone numbers, license plate numbers and other marks that, when decoded, function as intergroup communication. Some simply write muhajwel, as in a person who practices hajwalah.

Hajwalah has become an alternative escape from heavy social and religious restrictions; a solution to boredom and lack of engagement with the rest of society.

The leading Saudi newspaper Okaz gathered a number of young people engaging in hajwalah together with some of their supporters and opponents, and set up a forum for a confrontational discussion. One muhajwel, Abu Nimr, said that he doesn’t fear death as long as he prays and keeps his faith strong, and that performing such dangerous activities rids him of fear by default. Another participant, Abu Badr, added that “whatever is forbidden is desired” – be it car drifting or graffiti. Perhaps linking this phenomenon to the broader socio-economic conditions faced by the country’s youth is not immediately obvious, but given the social structures and forces within Saudi society, it seems that criminality and resistance to the status quo – or deviance – is inevitable.

Recently, some hajwalah youth have taken to some quite extreme and life-threatening levels of endangerment, which has led to the creation of the sub-category darbawy – a term that derives from the word darb, which means “path”. This phenomenon is no longer a mystery, as it has become a nation-wide known spectacle addressed even in mainstream media, whether satirically or seriously. At the same time, regardless of how much is written about it, the boredom that inspired the very movement continues to be overlooked and dismissed.

The muhajweleen with their spray cans are rebels without a cause – with their own, compound form of self-expression and resistance.

The graffiti, too. But the tags and messages on Saudi Arabia’s walls are not just scribbles. If read carefully, they are thick descriptions. Taking into consideration that more than 60% of the Saudi population is under the age of 30 and many are unemployed, the socio-urban phenomenon of hajwalah becomes intelligible. As their graffiti drifts through the country’s walls, it becomes apparent that they are not as passive or indifferent as they seem. They are also neither foreign to nor different from the global graffiti context.

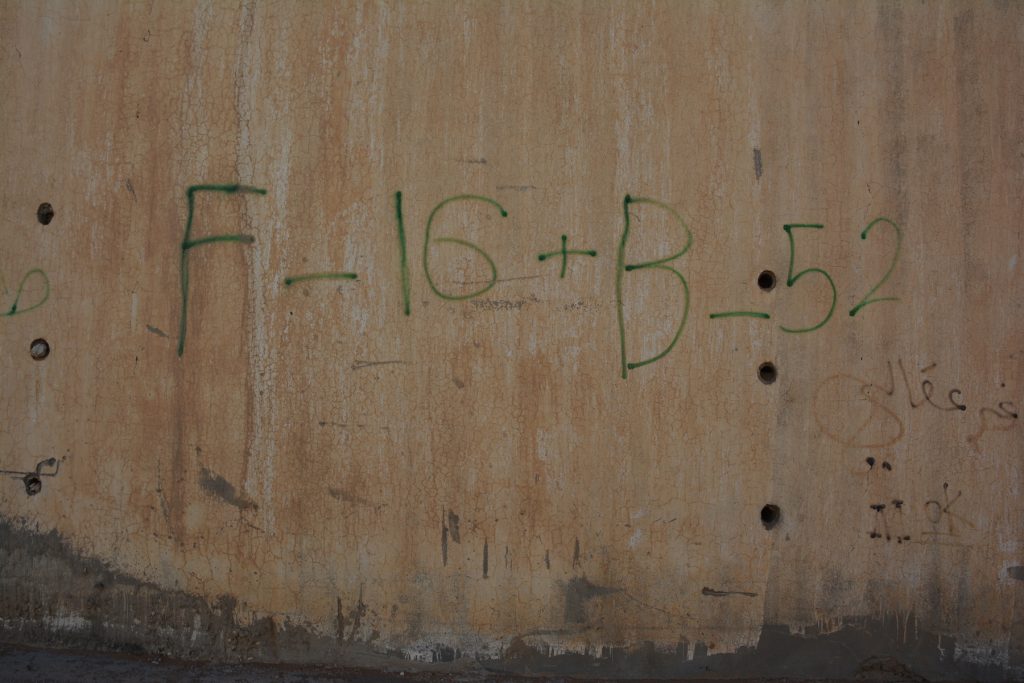

Messages have started to incorporate (or perhaps joined with) English words, skulls, anti-royal and anarchist symbols, slogans like “f*** the police”, and other rebellious imagery. The muhajweleen with their spray cans are rebels without a cause – with their own, compound form of self-expression and resistance.

The muhajweleen with their spray cans are rebels without a cause – with their own, compound form of self-expression and resistance.