Beyond the battle of Alexandria

Warning: Use of undefined constant ids - assumed 'ids' (this will throw an Error in a future version of PHP) in /home/clients/cbf26065d2af2a606c600e47be560e46/web/wp-content/themes/mn2/theme/inc/theme_functions_cleaning.php on line 61

Two years after the revolution, everything began again in Alexandria. January 25, 2013, a Friday, a day of prayer, was supposed to be the peaceful second anniversary of the revolution. But it ended up being a wave of chaos and violence.

“We did not start this. They did, with their gas canisters.”

In Alexandria, the battle between protestors lasted for twelve hours nonstop, mainly in front of the Maglis al-Mahalli, the Local Council, which currently hosts the offices of the Governor, whose previous headquarters were burned to the ground on in January 2011. The march started as usual from the central mosque of al-Qaid Ibrahim, an elegant building designed by the Italian architect Mario Rossi in the 1940s. One group, including more than forty factions, marched towards the Sidi Gaber Station, another marched to al-Mansheya Square, the heart of cosmopolitan Alexandria. The last stopped at the Local Council, after having walked along the Corniche.

Then, the battle started, with a storm of tear gas canisters fired from the rows of police stationed in front of the Council to protect it. Bricks and stones followed from the demonstrators’ side, as did burned tires and garbage caissons to dilute the smoke and decrease the irritating effects of the tear gas. People on the street said: “We did not start this. They did, with their gas canisters”. The gas inflames your throat and your eyes, and you cannot stand it for more than a few seconds. You have to run away as fast as you can. Some of the young people I met said: “This is stronger than what we are used to”. In fact, many of the at least one hundred injured demonstrators from Friday’s protest experienced a gas shock. Very few had gas masks – most used things like scarves, onions, ski glasses, vinegar or a mix of water and an antacid medication named Maalox to alleviate the pain slapping their faces: different ways of protecting themselves which, after all the demonstrations, the Egyptians know well. Inhabitants of the old Koum al-Dikka district were distributing paper handkerchiefs to the protesters, and pointing out ways of escaping the gas gusts.

Koum al-Dikka, a working-class district situated on a hill behind Alexandria’s Latin neighbourhood, is a peculiar area. The Local Council, an ugly building, is located right next to it, in the corner between the Central Station and the Greek-Roman Theatre. Koum al-Dikka is a unique place full of memories, with traditional craft workshops, back-streets and labyrinths, hidden old cafés, decaying buildings and kids everywhere. A person who has never entered the area cannot understand the simple soul of the city: a mixture of community, proximity, modesty and decadence.

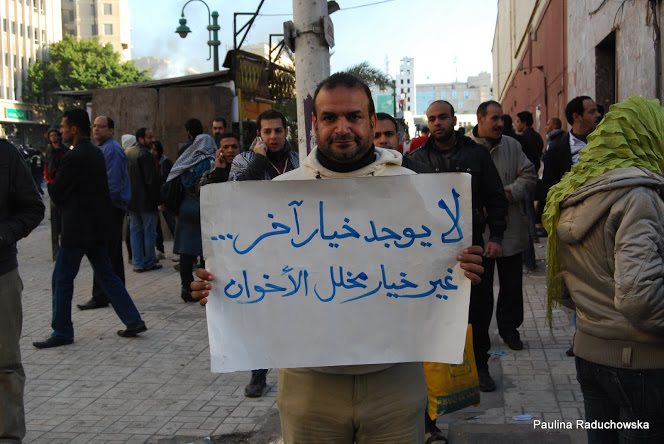

I still remember the uniform dark colour of the sky over al-Mansheya on that “Friday of Anger”, in January 2011. The sky over Koum al-Dikka two years later was grey and foggy. It was another sky, a sky of nonsense, of no-exit, of confusion and frustration. If two years earlier the “enemy” had been clear and present (the Mubarak regime), today’s target is vague. Is it the Muslim Brotherhood? The Ministry of Interior? Crazy fragments of the old regime? Or the army, which prevented the completion of the revolution during the transitional phase, before handing power over to the newly elected president? Or is it all of them? And who is defending the revolution now? Is it political Islam? The liberals? Or maybe neither of them, but instead the Ultras?

Even the Koum al-Dikka dwellers are confused. Friday night, they pulled out the demonstrators because they were tired of chaos. It is difficult to criticise them – bombs and tear gas destroy the nerves of even the most brave souls. My friend Mohammed, who was braver than me, joined the front row of the protest to catch a gas canister and examine it, but returned empty handed with dark violet eyes, coughing like an old smoker. In a public statement, the spokesperson of the Muslim Brotherhood’s Alexandria wing, Anas al-Qadhy, announced that day that: “We organized 63 charity fairs, 49 medical convoys, 8 festivals for youth employment providing 6,000 jobs, 23 campaigns for paving streets and 16 campaigns for gardening, painting sidewalks and walls … This is the difference between the Muslim Brotherhood’s commemoration of the revolution, and other forces which claim to be civilian, but commemorated the revolution by spreading violence and chaos”.

On Sunday evening, January 27, President Morsi announced in a televised speech the imposition of martial law in the cities of Port Said, Ismailia and Suez, a measure justified by the need to protect state institutions. But even the policemen were confused about the intimidating measures: in a moment of calm, one of them took off his helmet and joined the demonstrators in front of the Local Council, chanting: “Down with the regime of the Mourshid!” (“the Mourshid” refers to the Muslim Brotherhood’s Supreme Guide, or leader).

On Saturday evening, at least four of Alexandria’s police stations witnessed sit-ins by policemen protesting the fracturing of Egyptian society. At the Abou Qir Street station, policemen hung a big banner that read: “The people and the police are one single hand!”. Kareem, one of the young people in the crowd, told me: “There’s no safety any more. The police don’t want to be the scapegoat for a bad leadership; they don’t want to shoot at people because of social frustration. Many don’t want to serve a repressive apparatus like they did during the Mubarak era.” That same day in Cairo, policemen upset about their unsafe working conditions prevented Minister of Interior Mohammed Ibrahim from entering the police mosque to pray for an officer killed in Port Said.

In fact, safety is yet again an issue for Egyptians. Mohammed and I saw young men with long knives moving freely during the clashes of January 25; a couple of them even had revolvers. The demonstrators were confused: Who are these armed people? I saw one of them confiscating a long knife from a teenager. On Saturday night, neighbours were building barricades at the end of their residential streets, and watching over the persons walking by with wooden sticks and iron bars – a scene that mirrors my memories of the 18 days of the 2011 revolution. The streets that night became the scene of an urban guerrilla warfare. Street lamps were turned off, garbage containers burned and the asphalt covered with stones. Similar things took place elsewhere. Scenes resembling civil war, with fire and smoke in the streets, were broadcast from Port Said after the death sentence of people involved in the Port Said stadium massacre was announced. After the ruling, the prison of Port Said was attacked and 30 people died – adding disaster to disaster.

“Egyptians are frustrated because the Muslim Brotherhood are just a ‘copy-paste’ of Mubarak’s regime, and use the police to oppress peaceful demos,“ said Rasha, who was surprised by the intensity of the police’s chemical warfare in central Alexandria. Scenes from Cairo show another kind of frustration. On Sunday, people from the poor al-Dawiqa neighbourhood were demonstrating, for the third consecutive week, for their rights to housing. “The revolution of the hungry is approaching,” they chanted.

The reasons of the frustration in Egypt are several: justice for the crimes committed by Mubarak’s regime has yet to be delivered, people have not seen any clear signs of an upcoming social justice policy, and many old security and media figures continue to play key roles in post-Mubarak Egypt. “Nothing works any more in this country”, Mohammed told me at the end of that long Friday in Alexandria. That is something that everybody must do something about – not least the President. Alexandria, and Egypt’s other cities, deserve it.

The sky over Koum al-Dikka two years later was grey and foggy. It was another sky, a sky of nonsense, of no-exit, of confusion and frustration.

Edited by Stephanie Watt, all pictures by Paulina Raduchowska.

2 thoughts on “Beyond the battle of Alexandria”