Educating out of the box

Aziz Nesin’s living heritage

Right outside the urban center of Istanbul is a big white edifice, home to children without parents. But don’t think of it as an orphanage – it’s “a big house for a big family”. The place is the creation of Aziz Nesin, one of Turkey’s biggest writers and a progressive thinker who thought education should always bring out the best in children.

We are around 60 kilometers from Istanbul’s historical center, on the western edges of the gigantic metropolis. The road curves slightly toward the left. Even though urbanisation is coming this way, the area still has a countryside feeling. That’s why Istanbulites come here every weekend to enjoy nature and a bit of fresh air in the many outdoor barbecue restaurants that have opened along the main road. But some also come for a more cultural purpose. One of the properties here differs from the farms and houses. It was owned by Aziz Nesin, one of the biggest Turkish writers of the 20th century, born in 1915 and died in 1995 at the age of 80.

People who work here will tell you it’s a big house for a big family.

But the visitors don’t come to meditate at his grave: Aziz Nesin was an atheist and decidedly did not want to be buried. His ashes have instead been scattered somewhere in the main garden, which is full of fruit trees. The house, though, is not a house turned into a museum. Aziz Nesin did live here, but decided in the 1970s to use his royalties to kickstart and fund the Nesin Foundation. Through it, he built a five-storey white facility to host children who had either been abandoned or came from underprivileged families. But don’t call it an orphanage. People who work here will tell you it’s a big house for a big family.

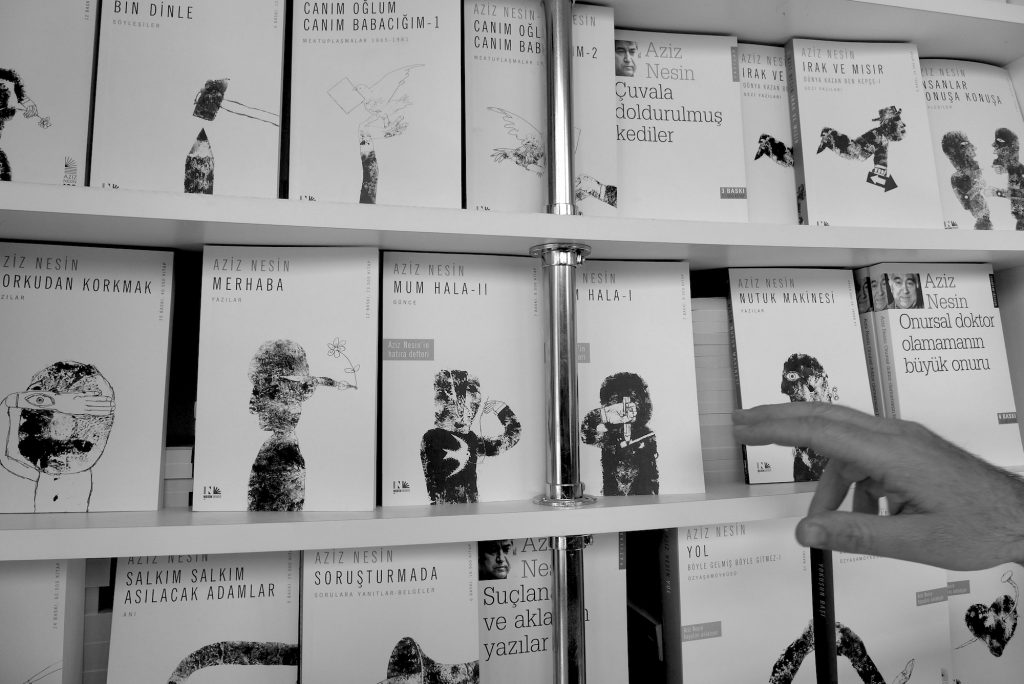

A sign top of the arched gate at the entrance says Çocuk cenneti, Turkish for “Children’s paradise”. When you enter into the main building there are several cupboards with copies of Aziz Nesin’s books, all of them released by the publishing house belonging to the foundation. They are plenty – Aziz Nesin wrote more than 100 books, from novels, theatre plays and comics to memoirs, poetry and essays.

“I wrote more books than my size, but people who don’t like me would emphasise the fact that I am small”, Aziz Nesin often joked. He was indeed rather short.

Coming from a very poor family, Aziz Nesin struggled most of the time to make a living out of his artistic calling. In order to make ends meet he wrote plenty of short stories for newspapers, always with a humorous and even satirical twist. He liked to depict the absurdities of bureaucracy, social norms or power. Being an outspoken voice and engaged left-leaning intellectual, he also spent several years in custody, which inspired him to write many stories set in the prison environment.

At a time when Turkey is seeing a worrying rise in mass arrests and authoritarian leadership, Aziz Nesin’s works seem more relevant than ever. Atay Eris, the publishing house manager, is quite happy to have seen sales go up during the past years. “We sold 200,000 books from Aziz Nesin in 2015, and the most sold one was Şimdiki Çocuklar Harika”. This all-time Nesin best-seller from 1967, whose title translates to “Today’s children are wonderful”, is an epistolary novel where two kids, Ahmet and Zeynep, write about their lives at school and at home, describing how they perceive adults’ rule. In this book, Aziz Nesin shows his commitment for a kind of education that focuses firstly on children’s needs.

In one of his texts, Aziz Nesin stated that “forbidding is forbidden at the foundation”.

Atay Eris did not know Aziz Nesin personally, and wasn’t an avid reader of his books until getting his current position when the Nesin publishing house was created in late 2004. “For a long time I, like many intellectual people, belittled Aziz Nesin. I read him when I was young, but then thought his writings were only for kids and moved on to other authors,” he says. Now, Atay Eris is impressed by the works and social commitment of the writer. “All his life, he thought he had to pay back to society because he was educated in state schools through people’s money. But it’s impossible to pay back such a debt, so he gave what came into his hands. He was a very special man. Once he set his objectives, he followed that without listening to anyone.”

Despite many bureaucratic hurdles, the Nesin Foundation has continued until now, and has even expanded slowly. They don’t receive state funding, but live on Aziz Nesin book sales, donations and a few real estate investments. Around forty kids and teenagers stay at the house in Gökçeali. The director since 2009, Süleyman Ciğangiroğlu, is a former boarder himself, who arrived at the age of 12 from Şırnak, a small Kurdish city close to the Syrian and Iraqi borders. He lived for a couple of years with Aziz Nesin, then graduated from the Istanbul Mimar Sinan art school. He never really planned to become the foundation’s director, but is now working in the same office as the famous founder. “It is a 24/7 job because the foundation is like a family. That’s why we work with a big team of around twenty employees. It’s a tiring job but also a delightful one, thanks to the children. Without them, this building would have no meaning.”

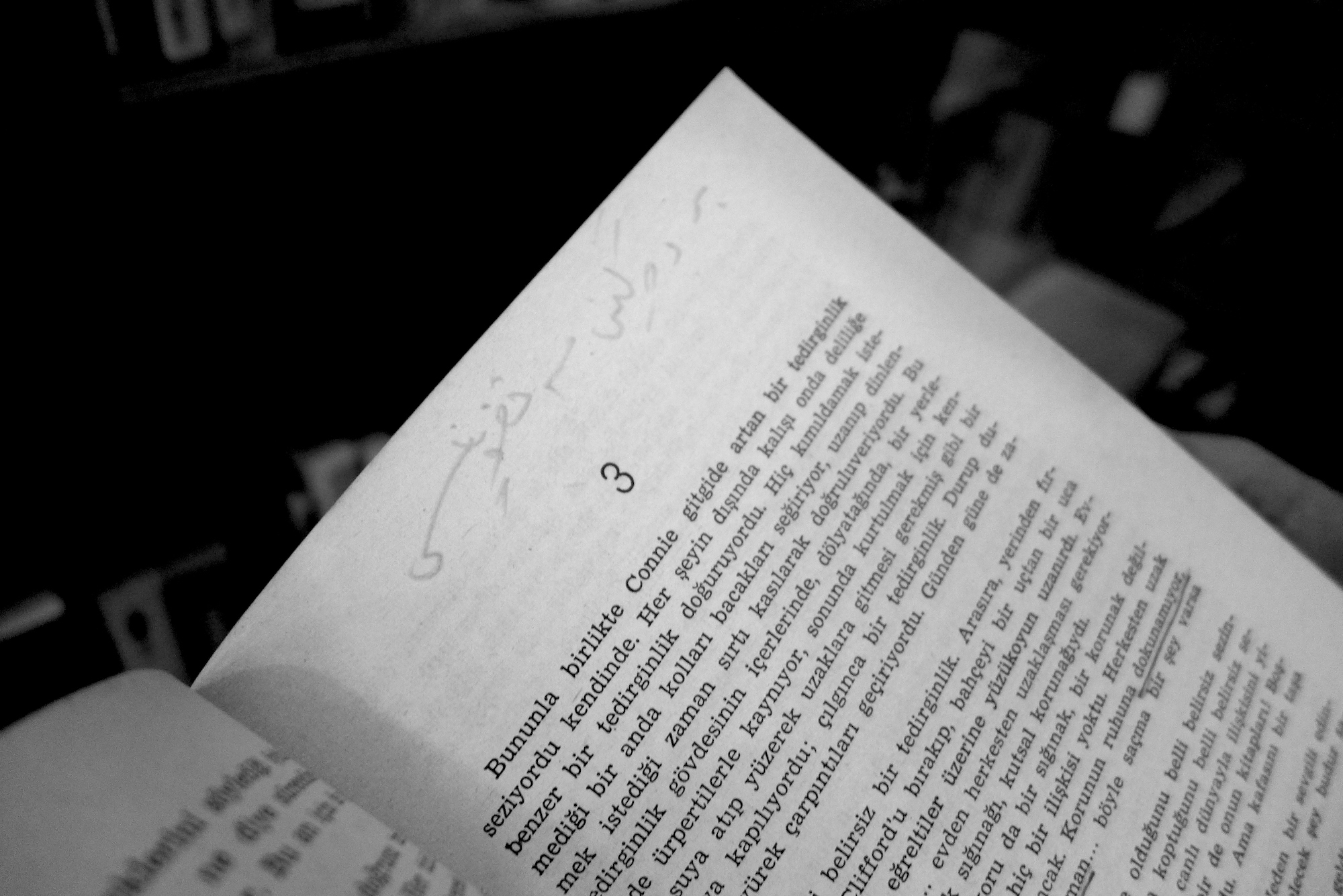

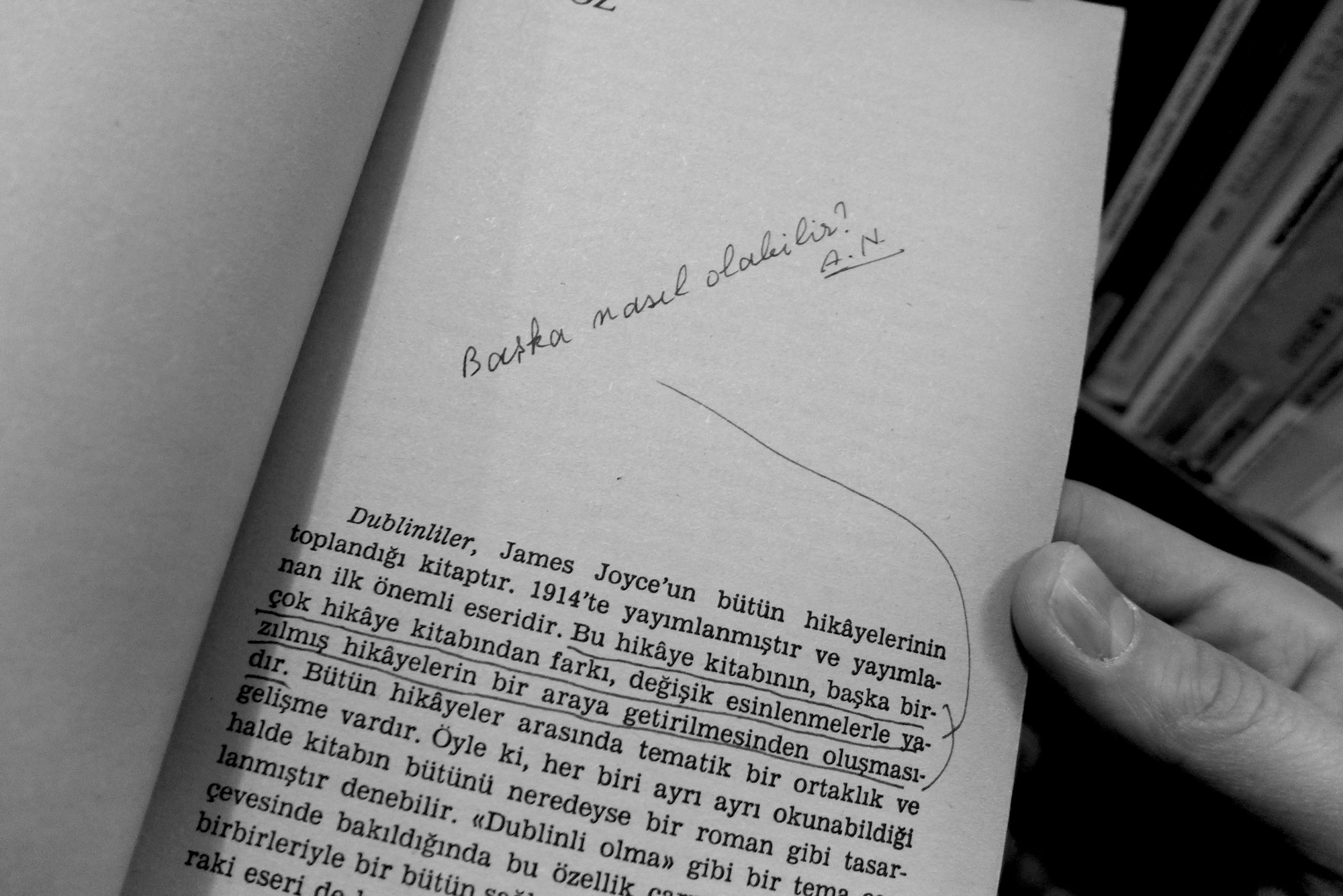

The director’s office is located next to the library, with a huge collection of books inherited from Aziz Nesin. Some of them has his Arabic handwriting; he was schooled before the introduction in Turkey of the Latin alphabet and preferred to take notes in Ottoman Turkish. When living in the house, Aziz Nesin spent a lot of his time in his small apartment on the top floor right above the children’s rooms; this is the place where he would be writing on his typewriter. All furniture and objects in the room are still from him. While living his life as an open atheist, he was raised as a pious Muslim and knew the Quran very well and mastered the art of calligraphy. Several of his calligraphy pieces hang on the wall, next to literary prizes.

Children have their say: everyone can express their feelings and ideas on current issues and upcoming projects.

The Nesin Foundation welcomes around five new kids each year, giving priority to those who have an appetite for studying. Unlike in Turkish state institutions, children are not kicked out once they turn 18, but can stay and get support until they find their own ways in life and become self-sufficient. “We want to raise good people according to Aziz Nesin’s principles,” says Süleyman Ciğangiroğlu. “We want children to not take anything for granted, but ask “why?”. “We want them to criticise, interrogate – not bow down to those who are more powerful.” The foundation puts this into practice through organising regular “family meetings” where children have their say: everyone can express their feelings and ideas on current issues and upcoming projects.

“We want them to be useful to society and honest. We want them to eventually do the profession they like. That’s why we offer them various possibilities: we do workshops, events, camps, and we try to go abroad,” continues the director. Aside from school, the children have plenty of opportunities to develop hobbies. They can borrow books from the big library or get lessons in painting, dancing, ceramic, music, theatre and sports. There is also an educational farm nearby, where they can get accustomed to breeding animals.

In fact, the facilities themselves show this idea of blending art with life. Walls are replete with book shelves or art works, and there are two pianos in the dining room. Next to the library there is a big space with sofas where films are screened – even though television is prohibited, as Aziz Nesin wished.

“Some of them came here, and they felt that it was the Nesin Foundation that took them from their families.”

The director of education, Özgün Dündar, is playing basketball in the playground behind the main building. She rolls up the sleeves of her dress, walks a few steps and takes a shot. “One must always do a bit of sport,” she says, smiling. This is one of her rare moments of free time during the day: she is responsible for the children’s daily programs, for supervising the caregivers and coordinating the extra lessons and psychological support. Her mission, she says, is also to make sure that everyone respects Aziz Nesin’s liberal vision of education. In one of his texts, the writer stated that “forbidding is forbidden at the foundation”. Özgün Dündar says that she has thought about that line a lot. “In fact, there is no outright ban,” she says. “When there is a rule, we explain its causes and consequences. Sometimes you need to be strict, but we do not give orders. There are no punishments either. If, for example, two kids are beating each other, we sometimes put them in the same room until they make peace.”

On the windows of Süleyman Ciğangiroğlu’s office sit small notes from the children, wishing him a happy birthday. But of course, he says, not all days are rosy. “I don’t want to paint a pink picture. There are some children who come here, remain unhappy, and leave.” He recalls the situation in Turkey in the 1990s, when many Kurdish villages were emptied and families forced to migrate to the cities, without being able to care for all of their children. “Some of them came here, and they felt that it was the Nesin Foundation that took them from their families. They were accusing us, making troubles, escaping – here, children do not stay by force. But their families would not take them back. I talked to one of them recently, who is currently working as a volunteer and studying in Germany. He remembered that he was very angry when he came here, and during the first three months he always kept his bag with all his belongings ready.”

Many who have stayed and grown up at the foundation remain in touch, and form a community that keeps Aziz Nesin’s educational principles alive, at a time when Turkey’s educational system is heading in the opposite direction. When Süleyman Ciğangiroğlu needs a helping hand, they are there to give it. And they come with their families to celebrate yearly events, such as “Children’s Day” on 23 April and the May picnic, a tradition started by Aziz Nesin when the 1st May celebrations were banned in Turkey. Another picnic is held in July, to commemorate the death of Aziz Nesin. But this is not meant to be a boring or sad day – instead, children, employees and attendees come together casually to share food, have fun and celebrate life. A simple tribute to thank the founder and wishing that his legacy will last for long.

Illustrations by Istanbul-based illustrator Mert Tugen. The article was written thanks to the help of a reporting grant from SCAM. It is part of the Web Arts Resistances project, in collaboration with Babelmed, Inkyfada, ONORIENT, Radio M and Tabasco video.