Shatila re-collected

In this introduction to our recently published anthology Beirut Re-Collected, Mashallah News co-editor Jenny Gustafsson recalls an encounter with the residents of Shatila, a Palestinian refugee camp in Lebanon with an infamous tragic history.

As Israel relentlessly attacked the people of Gaza over the past month, the media was saturated with appalling reports of civilian deaths, infrastructural destruction, resource depletion and the like, highlighting more than ever before the unbearable nature of life in the strangled strip.

This endless newsreel of calamity, however, was occasionally interrupted by stories of Palestinian perseverance – of Gazans’ seemingly inextinguishable ability to literally lift themselves out of the rubble that once was their homes, carry each other’s injured bodies to safety, and find ways to carry on despite their impossible circumstances, confident in and comforted by a sense of righteousness that fuels their love and desire for life.

In light of the bombardment and in honour of the steadfast Palestinian spirit, we thought it fitting to share this brief vignette about the resilient residents of Shatila who, despite the scars of their past, still sensitive to the touch, and the less than favourable living circumstances they must make do with, continue to command attention with a charm and personality that can only be rooted in the firm conviction that their struggle has not yet been squashed, and their cause is far from over. These people and their stories must not be forgotten.

B13 in Beirut

It is a warm and sticky afternoon. We take the minibus from Cola, the busy intersection in Beirut named after the Coca-Cola factory that once existed in the area. After a short ride, we get off at the side of the road south of Shatila, one of Beirut’s Palestinian refugee camps. On this early midweek afternoon, the roads are not yet busy. We cross the street, exchanging a few words with a woman who came on the same bus. She carries shopping bags in her hands and her eyes are kind.

“Do you live here?” we ask.

“Yes, my house is right there.”

She points to the other side of the road, where small two and three-floored houses stand close to one another. Typical suburban Beiruti houses, made of grey cement with square windows and bright textile shutters that offer shelter from the sun. Street vendors occupy every centimetre of the pavement in front of the house. Each displays wooden furniture, plastic chairs, and red, blue and bright green kitchen utensils. The vendors smile at us as we pass by, asking us to stop for a minute and take a look. Surely there must be something we need. A stool? Maybe a Persian rug?

We don’t buy anything; instead, we make a right at the next crossing, where the street suddenly turns into a market. The point at which the street ends and the market begins is easy to detect: heaps of worn-out shoes and heavy coats, neat rows of shampoo bottles, shiny-but-cheap jewellery, and piles of pirated CDs and DVDs mark the spot. We ask a vendor with a particularly impressive collection of records if he has anything with Remi Bendali, the Lebanese child singer who was popular in the 1980s. It’s Ismaël who’s looking for it: he grew up on her music. But the vendor shakes his head. No, nothing at all from the eighties. He has other records, though. New stuff, like Elissa or Myriam Fares. He turns up the volume. The tunes spill out into the street, where they mix with announcements that the apples are baladi (local), and the pants are three for the price of two.

We keep walking, no CD in Ismaël’s hand. Passing us by are old ladies and men, parents with their kids in a tight grip, teenagers with phones in their hands. It’s not long before we’re in Shatila. We take one of the small roads that lead away from the main street, following a wall with colourful drawings and graffiti. There’s a painting of the Al-Aqsa

Mosque and a white dove aimed at the sky. Next to it, in red, green and black, the word Filasteen. Palestine. The letters make for nice graffiti.

On our right is a small place serving foul and balila: beans or chickpeas with oil, lemon and garlic. They are breakfast foods, so the first servings were probably handed out hours ago. Now, the plastic chairs and matching tables are empty. Two boys are busy with the last bit of cleaning up. Another — their big brother, we soon find out — invites us to sit down. “How are you doing? Just walking around? Yalla, take five minutes and drink coffee.” He asks one of his kid brothers to bring us coffee; the brother does, in small white cups. The waiter takes out his phone and asks us to note down his number. “Just in case you need anything — help, whatever. You can call me. Really, do.”

The empty lot makes a perfect window through which you can see a tiny open space: a splash of green, where a group of children are playing

After looking down at the black circles left in the bottom of the cups, we sit for a few minutes, gazing at the houses on the other side of the street. They sit jammed tightly next to one another, just like all the other buildings in the area. People are erecting a new house where an old one used to be. The remains of the outer walls are still there; inside, bags of cement, shovels and a cement mixer. The empty lot makes a perfect window through which you can see a tiny open space: a splash of green, where a group of children are playing. Pieces of plastic dot the ground and the grass is half-covered in cardboard. Once the new house is up, the breakfast eaters will have no greenery in sight.

We leave our table and step out from the restaurant. The air is still warm, although the worst midday heat has passed. Right after the wall with the drawings, there’s a sharp corner, marked by a few strategically placed chairs. An elderly lady and two men are seated, talking to each other in short sentences. Every time I pass this spot, I wonder about the chairs and the seniors, and how they like to spend their days on that corner.

On either side of the road are houses, houses, houses. Facades in different shades of grey, or painted pink or yellow. Satellite dishes on the roofs, wires and cables in between them. The clothes hanging to dry from the balconies reveal a bit about the families who live inside. How old their kids are, if teenagers live there (and if they do, what kind of teenagers they might be).

Five minutes later, we’re almost on Tareeq al-Matar, Airport Road. Adorned with a worn-out banner in one of Lebanon’s many political colours (put up by one of its many political parties), we walk towards the entrance, passing small shops and businesses — places where you can top up your mobile credit or buy cigarettes and sodas, or shop for cheap tomatoes and cauliflower.

Outside an auto-repair shop are two chairs, this time with young men, not seniors, seated on them. Someone among us starts the conversation. Their names are Alaa and Abdo, both in their early twenties. Alaa wears a t-shirt that says “Armani.” Abdo has one with the Union Jack. Both are in flip-flops and sit with their gaze resting on the horizon. They’re friends and colleagues.

“But this is not where we want to be. We want to get out of here. Leave the camp, go somewhere else. Work with something meaningful.”

Alaa tells us his sister is in Germany. He wants to do something similar. Go elsewhere. Somewhere with opportunities. Different from the isolation, wartime memories, minority politics, electricity cuts, and flooded winter streets of the camps.

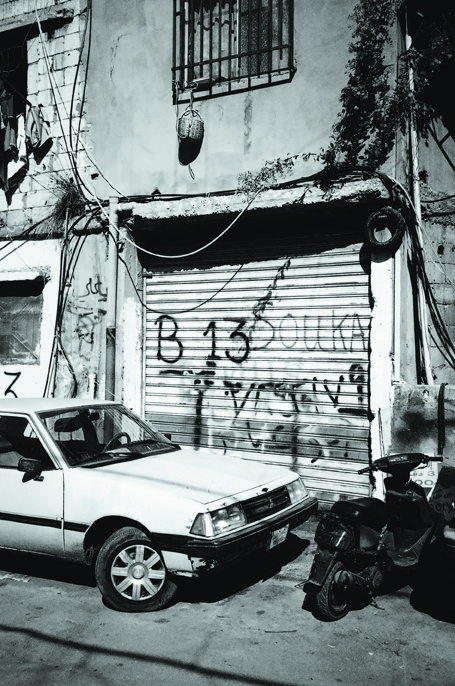

A scribble on a small house facing the workshop catches our attention. On the turquoise metal shutters, someone has written “B13” in large letters.

“It would be great to include it in the book. To write about their lives, the kind of things they deal with. Why they feel they’re living in a place like B13.”

“It’s because this area is like B13. You know that film? About gangsters in Paris. Guns, drugs, no law. No future. It’s like that here. It’s like living in B13. So we drew it all over the neighbourhood.”

Abdo points to other, similar, graffiti. One on another wall outside, and another inside the workshop: “B13” sprayed in silver letters.

We stay around for a while longer, talking about the movie and how it’s actually pretty bad, unlike Luc Besson classics such as Léon or The Big Blue. As we walk away from Alaa and Abdo, we pass by a few more walls with “B13” written on them. Out on Tareeq al-Matar, we catch a minivan passing by Martyrs’ Square en route to Bourj Hammoud and Dora. As we spread out on the seats in the empty bus, we talk about Alaa and Abdo and their story.

At this time, we were working on putting together the content of Beirut Re-Collected. For five weeks, we were gathered in Beirut, collecting stories about people and places in the city. This afternoon in Shatila was towards the end of our stay. Two days later, we all hopped on flights: the graphic design team to Geneva, one editor to Istanbul, another editor (this one) to Bombay.

“Okay, so tomorrow, I’ll go back and ask them to tell their story.” But, as it turned out, that didn’t happen. The day after, a Friday, was brutally interrupted by the news that a bomb had exploded in Ashrafieh. Its intended target was killed, along with several others. These kinds of things are not new to the city — on the contrary, they’re considered the norm. But the explosion came unexpectedly and sparked protests that led to the closing down of parts of Beirut and other cities. There was no time or possibility to talk to Abdo and Alaa the day after.

When we finished this volume, we still hadn’t written a chapter about the story of B13 in Shatila. And that’s why we wanted to tell it asan introduction. Because it reflects the purpose of the book: to share stories that are lost. Stories about people or places that, in one way or another, are forgotten, missing, unseen, or unheard.

First paragraphs by Sophie Chamas, picture by AMI.