Should I pay or should I go?

Military service in Turkey

For many youth across the world, the rites of passage include university, graduation, then possibly marriage. For others, including young men from Turkey, the extra expectation was for long the military service. Until recently. You are now allowed to pay your way out.

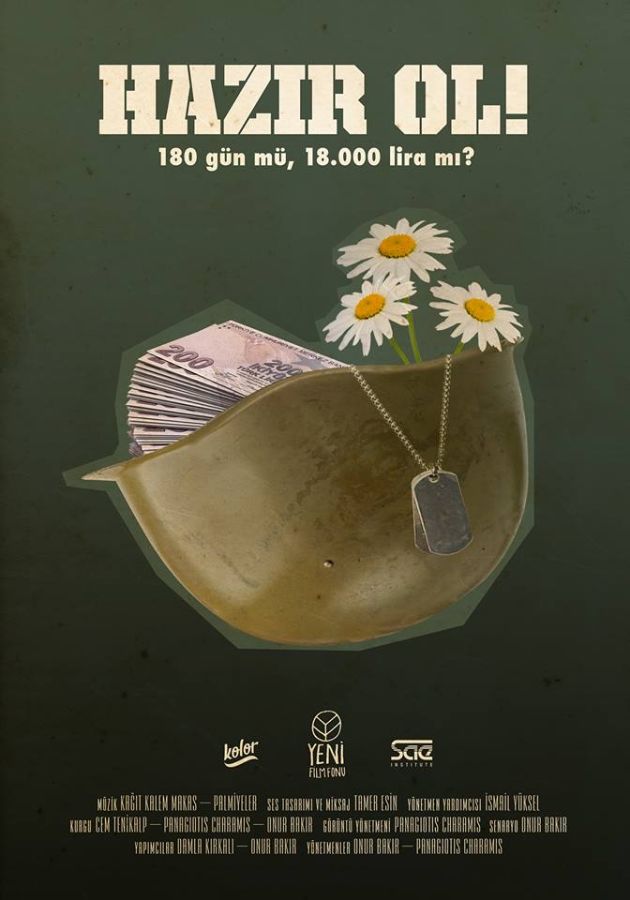

Since the Turkish War of Independence in 1919, military service has been compulsory for all men between the ages of 20 and 41. University graduates serve six months, non-graduates 12. Indeed, the 1980 constitution reaffirms that national service “is the right and duty of every Turk”. But when the government in November 2011 introduced “paid military service”, a payment of 18,000 Turkish lira ($6,173) instead of six months in the army, many started asking themselves: “Should I pay or should I go?”

For PhD student Onur Bakır, this became the starting point of making the film Hazır Ol! (Attention!), which won Best Documentary Award at the 2016 Istanbul Film Festival. The film was co-directed with Panagiotis Charamis, and Bakır himself plays the main character, talking to relatives, friends and experts, asking for advice about his harsh decision. The movie aims to spark a debate on the touchy issue of military service in a country where the right to conscientious objection is not recognised.

“Especially if you are running a business, have a regular job or are about to get married or already is, it is very hard to interrupt your life with military service,” says Bakır. Turkish society and the state leave little room for men to maneuver out of it. “Not going is also an obstacle, because every job application asks, ‘Have you completed your military service?’”

The only way to avoid the obligation is being declared physically or mentally unfit. People who are openly gay are also excluded from the military (another documentary, “Çürük, the pink report” from 2014, deals with this issue). Proving that you are gay used to sometimes involve humiliation such as having to wear women’s clothes in front of military officers or submitting explicit photographs. The regulation was amended by the Turkish army last November, and it is now sufficient to declare yourself gay during the pre-draft medical examination.

Bakır is currently working with a Boğaziçi University project to bring philosophy lessons to children in Turkish schools. One might guess that he is not the most willing or suitable army recruit. “I think military service would be very difficult for me psychologically,” he says. “I would be an outsider because of my education, me being from Istanbul, my political ideas.” Indeed, with liberal views, Bakır might not be warmly welcomed in the military institution.

Bakır notes that the number of suicides in the army is higher than the number of Turkish soldiers killed in combat, which suggests, in his views, that the military hierarchy encourages abuse. “Being with so many men is a problem. Being ordered around by someone else is a problem. The conditions in the army in terms of food, toilets, showers and daily routines are not so good. Rules go before reason, so you can’t question anything.”

When the military did not allow filming inside the barracks, Bakır decided instead to focus his documentary on his own choice of paying instead of doing service. Talking to his family and friends had helped making that decision.

“I think any reasonable person would advise someone they love not to go. Ninety percent of my friends and family told me to pay instead,” he says.

Given the ongoing war between the Turkish army and the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK), there is a definite risk of injury or death.

“The remaining 10 percent said I should go because 18,000 lira is a lot of money, about one and half years of minimum wage. Then, some people just didn’t want me to go.”

As a compromise for conscientious objectors, Bakır suggests another solution: giving people the choice to serve by working for an NGO, being a librarian or doing social work, like reforestation. “I asked my mother if the 18,000 lira went to education instead of the army, would she pay it. She said yes. ‘What about health,’ I asked. ‘Yes.’ ‘Tourism?’ ‘No.’ ‘What about forestry?’ ‘I need to think about that’, she said.”

Before the movie, Bakır was already quite convinced that he would not go, but during the process of filming he became more aware of the complex attitudes of his family towards the military service. With no end in sight regarding the violent conflict with the PKK, the paradox might be even stronger: many Turks may approve army operations and be open to doing the military service, but would refrain from having their sons or relatives serve in the army at this risky point in time. And “Hazır Ol!” brings that exact issue to everyone’s attention.