The medium and the message

In the hidden villages of this small desert kingdom in the Persian Gulf, stories from the present and past can be found on the walls. Not only do they carry a political message in these times of change, they also highlight a territorial divide in Bahrain’s urban space.

The country’s graffiti scene, today and dating back to a few years prior to the Arab uprisings, is far too significant to overlook, particularly in the context of its recent transformation. The events of the recent February 14 movement in Bahrain may have come as surprise to the passive observers. The writing was, however, on the wall.

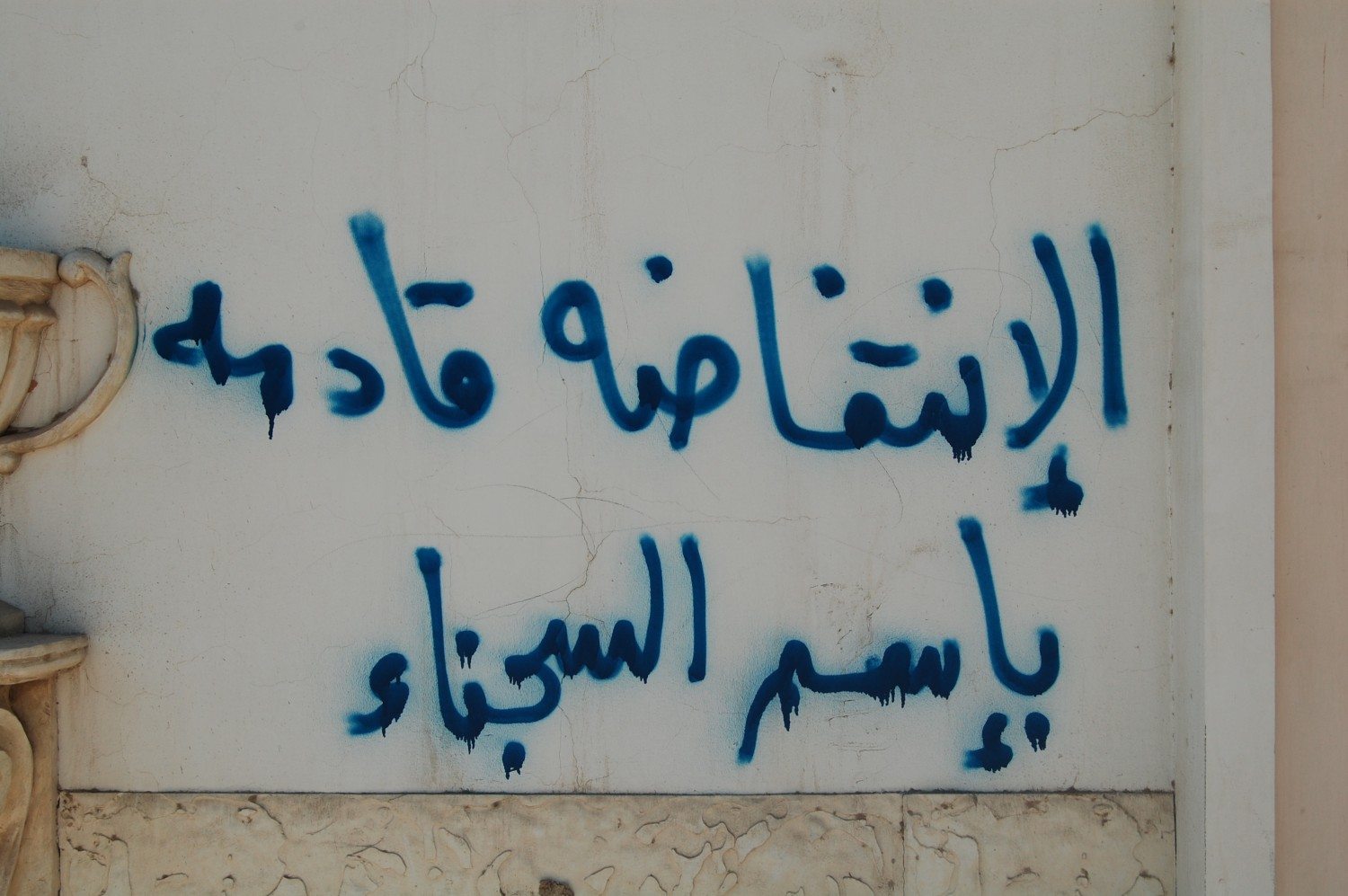

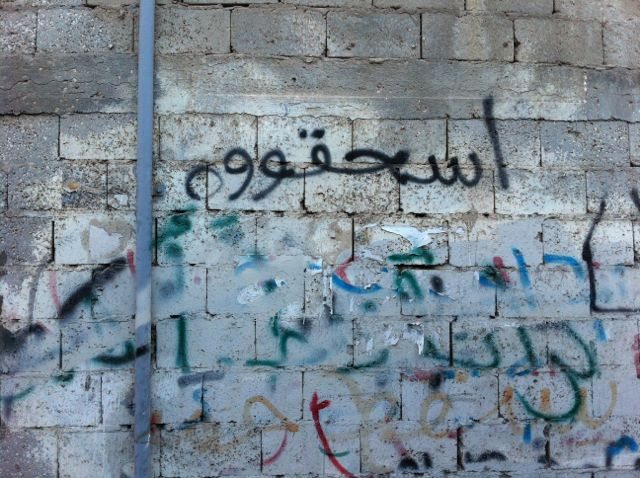

But there is a difference between city and village. On the main roads, only signs and advertisements can be found. When angry cries and messages get written on these walls, they are instantly painted over by the authorities. In the closed-off village communities on the other hand, the expressions on the walls are left uncensored, and reach the different audiences of passers-by. The letters on these walls take on human characteristics: graffiti shapes and fonts which are conceptualised according to their different motives.

The events of the recent February 14 movement in Bahrain may have come as surprise to the passive observers. The writing was, however, on the wall.

There are religious scriptures, aphorisms and historic references, written in colourful calligraphy by the villagers and showcasing influences ranging from the resistance in Lebanon to stories from Karbala and idols in Iran. A sense of belonging is manifested in these calligraphic writings, as villagers reveal their identities and mark their existence through them. There is an abundance of glorifications of Hussain, the “martyr of martyrs” and a potent symbol of resistance, as well as commemorations of the battle of Karbala. These motives emphasise the Shiite identity and its affiliations, which continue to inspire present day resistance and struggles.

The dissenting graffiti on the other hand, is characterised by anger and destructiveness, often visualised in vivid written forms. The recurring theme – the island’s sectarian tensions between a marginalised Shiite majority and a Sunni ruling elite – was expressed on walls long before the 2011 uprising. Looking carefully at the leftovers of old graffiti, one can still trace the barely visible word “parliament” and other references to a past uprising calling for the reinstatement of the 1973 constitution. The sectarian nature of this written dissent displays the unequal opportunities to education and employment among different Bahrainis, as well as the majority’s undermined representation in the political process.

The dissenting graffiti is characterised by anger and destructiveness, often visualised in vivid written forms.

There is also graffiti with more specific messages: demands for the release of political prisoners for example, which are in abundance in each prisoner’s home village. The most prominent figure idolised and stencilled across the island is Abdul Amir al Jamri, the spiritual leader of Bahrain’s Shiite population and the 1990s uprising. These graffitied reminiscences of Al Jamri, both old and new, illustrate the need to hold on to memories in order to keep them from being diffused or altered. This is an attempt to preserve a collective memory, to which graffiti writers have made important contributions.

For a culture so accustomed to the graffiti medium, the new discords generated by the February 14 events have not necessarily encouraged more graffiti. It is rather the language, both the words and the images, that has changed. Most evident is the explicit call for the downfall of Bahrain’s ruler, King Hamad. Walls now bear the graffiti “Tn tn Ttn“, referring to sound of cars honking “Down with Hamad”.

The events following February 14 have fuelled a more steadfast opposition, making potential success in dialogue and reconciliation increasingly unlikely. This is seen in the graffiti too – after the regime used force to crush the demonstrations at the Pearl roundabout, graffiti to denounce it soon emerged. These drawings used stronger and harsher words than before, and a new importance was given to symbols and graphics. The Pearl icon became an immortalised such symbol, and was drawn on the walls along with the phrase “We will return”, in defiance of a devastating image of the demolished structure.

In current-day Bahrain, graffiti has a great political potency. Both the medium and the message signify a type of sociological thermometer that reflects current developments on the island.

As the violence continued, graphic representations became more contagious, highlighting a visible transformation of the Bahraini graffiti scene with different aesthetic forms and motivations. More martyrs and more political prisoners were stencilled, while drawings of women became new iconic figures, manifesting their significant role during the uprising. Other emerging examples were those with specific references to the Peninsula Shield, the Bassiouni Report and the calls for the Formula 1 Boycott, to name a few. The more visible and specific the graffiti, the more recently it was sprayed.

Aside from the new icons and change in tone, style and references, an unexpected new narrative joined the graffiti invasion. This was the pro-regime graffiti – something new for those accustomed to the pre-February 14 urban landscape. The resort to response (however harsh or provocative), as opposed to the habitual painting over of dissent, could be seen as an optimistic step in an otherwise absent dialogue. But it also represents a mockery of the pro-regime narrative, which has abandoned its alternative traditional media tools.

The Pearl icon became an immortalised such symbol, and was drawn on the walls along with the phrase “We will return”.

In current-day Bahrain, graffiti has a great political potency. Both the medium and the message signify a type of sociological thermometer that reflects current developments on the island. The familiar steadfast resistance is still there, clinging on to memory in both motivation and tone. The current graffiti, however, indicates a far more intensified struggle ahead.