Through Bahman Jalali’s lens

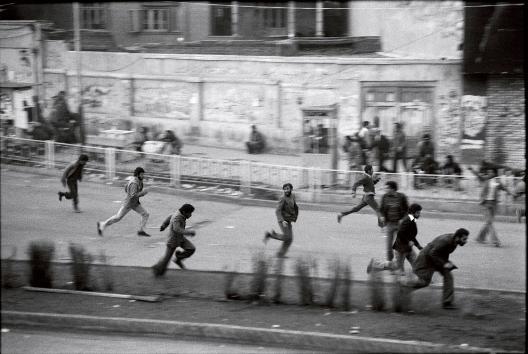

In October 2007, I had the unique pleasure of stumbling across the Fundació Antoni Tàpies during my first visit to Barcelona. I was struck by a black-and-white photograph dating to 1979 on the temporary exhibition bill (see below). It featured a group of men and women gathering outside a ransacked concrete structure with shattered windows and thousands of documents littering the street. A graffiti of Ayatollah Khomeini sprayed onto the plundered building overlooked the crowd as individuals stood in place feverishly reading and collecting papers by the handful. These papers were in fact sensitive material that had been stored in a governmental building; as the crowd read on, they slowly were uncovering the workings of the deposed regime’s bureaucratic and security apparati.

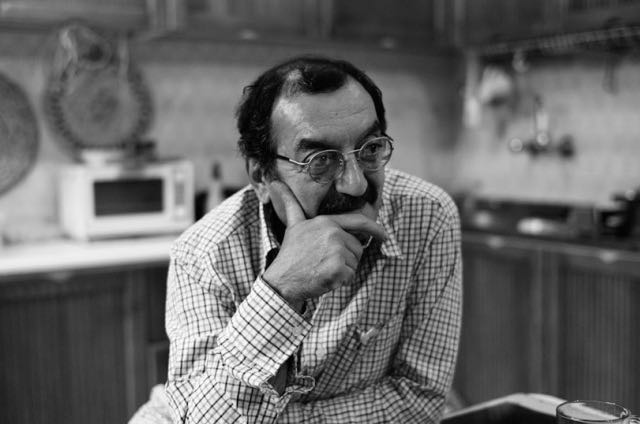

The photograph is a visual document of the revolutionary fervor and social unrest that rocked Iran from 1978 to 1979, and it has been adopted into the collective memory of the Iranian Revolution. It serves as a historical milepost, capturing an instant of momentous change– of a society throwing off the shackles of an oppressive regime and unaware of the one to follow. Mesmerized by the image, I felt compelled to enter the Fundació’s doors to see the work of Bahman Jalali (1945-2010), the photographer featured in the exhibition.

Born in 1945, Jalali developed a passion for taking pictures during his youth. While he originally studied economics and political science at Melli University in Tehran, he soon dedicated his life to photography and joined the Royal Photographic Society in Great Britain in 1974. From the same generation of photographers that included Kaveh Golestan, Jalali helped popularize Iranian photography within the general public and the international community. He gained notoriety for documenting the the tumultuous events of the seventies and eighties, producing iconic images of a country in the midst of transformation and defending itself from an imposed war with Iraq from 1980-88.

After the ceasefire between Iran and Iraq in 1988, Jalali traveled to various regions in Iran and captured aspects of quotidian Iranian life, such as the daily labor of the fishermen in Bushehr, the routine tasks of the residents of Massouleh, and the traditional desert architectural forms of Yazd. He later moved away from the documentary style of his youth and imaginatively experimented with negatives dating to the later years of the Qajar Dynasty that ruled Iran from 1785 to 1925 . While the Fundació displayed many series produced during Bahman Jalali’s career, I was captivated by his Qajar-era photomontages as well as his photographs chronicling the 1979 Revolution and Iran-Iraq War.

As I followed the various series of the exhibition chronologically, Bahman Jalali’s evolution as a visual artist was evident. A methodological feature of Jalali’s photography was his preference for pictorial essays that illuminated a particular time and place. His early work was concerned with excerpting images from the present which helped frame the visual history of Iranian Revolution and the Iran-Iraq War. Jalali himself understood the significance of his work during those years, stating that, “we construct history through photographs. They shape it for us.” With his later Qajar-era photomontage work however, Jalali came to reevaluate the position of photography within the creation of history: photography does not just document the present, but can extend back through temporality and shape one’s understanding of the past, acting as a bridge between history and collective memory.

We use our memories and experiences to make sense of a visual documentation of “what was.” However, while we sometimes imagine memory to be rooted in experience, it often is shaped by significant political shifts or changes in our own personal beliefs. Thus as time progresses, reevaluating photographs can dramatically reshape our own recollection of the past and help retrieve moments that have fallen through the cracks of our memory or excluded from a dominant social history.

His first series– titled Days of Blood, Days of Fire (Tehran 1978-1979)– was done in collaboration with his wife Rana Javadi and chronicled the popular uprising that overthrew Mohammad Reza Pahlavi. Taken over a period of sixty-four days, the series tracked the progress of the revolution from December 10th 1978, when millions of anti-shah demonstrators marched through the streets of Tehran, to February 11th 1979, when the final remnants of the Pahlavi regime collapsed when the Supreme Military Council finally declared itself neutral. Jalali produced iconic images of several major events, such as the departure of the Shah on January 16th and the return of Khomeini to Iran from exile on February 2nd.

“Photography does not just document the present, but can extend back through temporality and shape one’s understanding of the past, acting as a bridge between history and collective memory.”

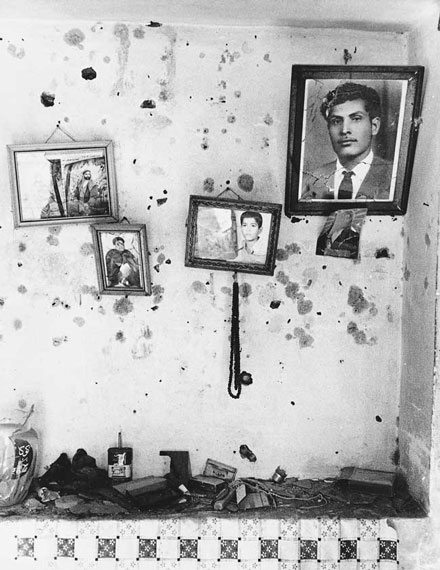

Jalali was able to document the Iranian Revolution from start to finish, as the events that occurred were happening all around him. However, his coverage of the Iran-Iraq War entitled Khorramshahr: The City That Was Destroyed (1981), seemed to have no end. Jalali traveled to the border town almost forty times from 1980 to 1988, recording the horrors of war through his lens. Khorramshahr, which Iranians nicknamed Khooninshahr (the City of Blood), was the site of Saddam Hussein’s invasion of Iran on September 22nd 1980. Jalali first visited the city in 1981, while it was still occupied by the Iraqi Army and visited more frequently following its liberation by Iranian forces in 1982. The struggle for Khorramshahr was central to the war-time psyche and memory of the 8-year long conflict. While the traditional historical narrative portrayed the city as a place of gallant resistance on the front-lines, the photographs illuminate its vulnerability and the catastrophic suffering of its people. As a chronicler of visual history, Jalali made sure that evidence of the war’s destruction would not be forgotten or ignored.

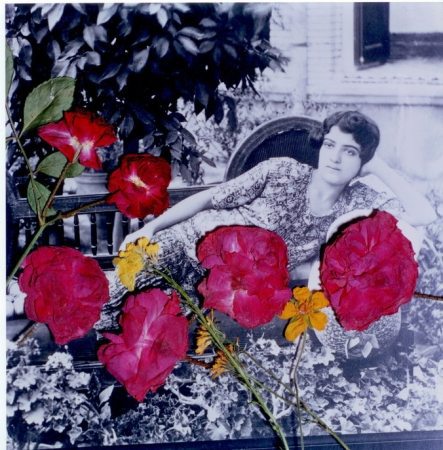

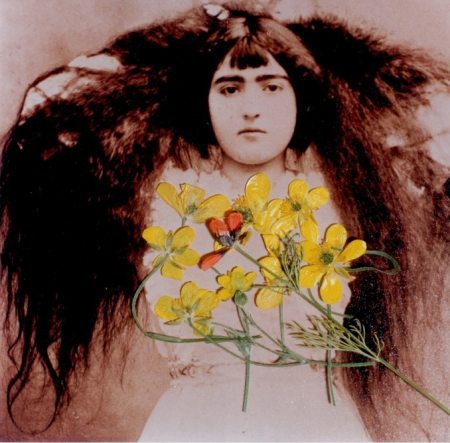

After thirty-some-odd years of photographic work constructing visual history, Jalali’s latest series emphasized the complexity of our understanding of history by playing with temporality and memory– crucial elements of the historical process. The culmination of Jalali’s artistic experience is represented in his Image of the Imagination: Black and White (2000) / Sepia (2002) series. It is a selection of photomontages of Qajar period negatives (from the photographic collection of the Golestan Palace) that take an experimental and innovatory look back at the history of Iranian photography.

These photographs, predominantly featuring women with colorful flowers pressed onto them, captured forgotten moments that had been excluded from the visual narrative of the age – one traditionally dominated by moustachioed men and courtly life. For Jalali however, this project was not just about reintroducing historical photographs to the present, but about placing them in an abstract world of their own: “I have been exposed to many images by little known photographers around the country. Those that I could keep, I have held as mementos, and others have left their marks on my imagination… These images gave way to a new world, one only found in the imagination. In the space between the tangible and the virtual, a world that brings these two realities ever closer has come into existence.”

“With his later Qajar-era photomontage work, Bahman Jalali came to reevaluate the position of photography within the creation of history.”

Jalali was not only concerned with the interwoven relationship between cultural history and memory, but also with the generational responses to a particular historical narrative. In Images of the Imagination: Red (2003), Jalali featured negatives from the Chehrehnama studio in Isfahan, one of Iran’s most important photographic studios from the early 20th century. Jalali came across the studio after the revolution and discovered that its sign had been defaced with red paint, apparently in protest against the photographs of unveiled women that had been taken there. While the Chehrehnama photographs themselves were apolitical in nature and frozen in time, they were received differently by Qajar Iran and Post-Revolutionary Iran. Inspired, Jalali blended the negatives and overlaid them with red paint and black calligraphy, mixing time and space and alluding to each era’s reactions to the images.

Less than three years after Jalali was honored by the Fundació Antoni Tàpies, the accomplished photographer and visual artist lost his battle with pancreatic cancer. Bahman Jalali’s lifetime of work serves as a visual testament to Iran’s social history. His early photography created an account of some of Iran’s most turbulent decades, depicting a country in metamorphosis. His later series pays homage to his predecessors, those photographers that developed a homegrown photographic tradition to document Iran’s emergence as a modern nation-state. While most of Jalali’s photographs helped curate a historical narrative of 20th century Iran, they also illuminate how Iranians have recognized their own history in alternating and perhaps quite contradictory ways at different moments in time.

Originally written by Rustin Zarkar and published by Ajam Media Collective.