Enter and exit Ankara

The five new gates of the Turkish capital

Melih Gökçek, the mayor of Ankara, is not only busy running the everyday goings-on of his city – he’s also seeking to establish a whole new identity for it. But not “new” in the literal sense – he longs for the bygone values of the Ottoman-Seljuk era: “Inşallah our gates, with their distinctive attributes and architecture, will become the symbols of Ankara. Our gates embody reminisces of Seljuk and Ottoman architecture, and, as a result, reflect our history.”

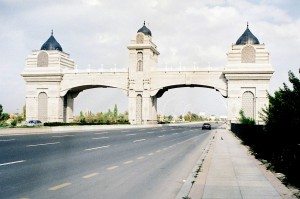

Gökçek might be aspiring to the status that Ottoman sultans possessed once upon a time. Under him, five new gates have been built, positioned at different highways leading out of the city and, combining the aesthetics of Seljuk and Ottoman architecture. To understand his attempt to cultivate a new national identity in the capital by drawing on the Ottoman past, one must look to Turkey’s current political climate.

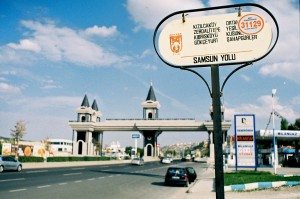

The main purpose of this urban reshaping is to solidify Ankara as the capital and Turkey’s second largest city, with sprawling connections to other important regions of the country. The new entrance gates adorn roads connecting Ankara to the four surrounding cities of Eskişehir, Konya, Samsun and Istanbul, as well as the international airport. “Each of our gates carries the historical traces of these cities, whose names they bear,” the mayor has stated. The capital is announcing its new identity not only to its local residents, but also to those coming from surrounding areas and abroad.

The designs of the gates reflect this new national identity and how it’s being branded as reflecting grand moments in Turkey’s past. The Seljuks paved the way towards Anatolia and remain closely associated with Central Asia and Turkish mythology, while the Ottomans conquered Istanbul and established hegemony over three continents. Gökçek’s gates borrow aesthetically from both the Ottomans and the Seljuks, and as a result have birthed a new, eclectic style. It clearly glorifies the past, but also leaves locals and visitors confused over which elements are Ottoman and which are Seljuk.

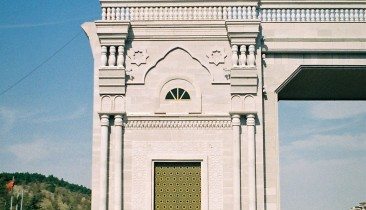

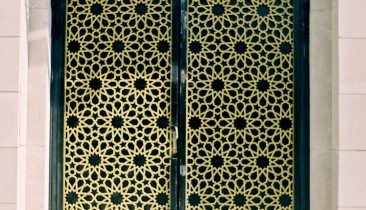

The gate on Konya Road reflects the Seljuk-era kümbets (left) – the tombs of society’s elite. It also utilises Turkish çini art (center), which was practised during Seljuk times. The octagonal star figure, also known as The Seljuk Star, symbolised immortality, sovereignty and perfection. On the Konya Road gate we see them forming a pattern on the columns (right). They also appear on the door, creating a sense of infinity and approximation to the eternal. When we consider that Konya Road connects Ankara to the city of Konya, once the capital of the Seljuk Sultanate, and the city of Rumi, this all makes sense.

The gate on Esenboğa Road, which leads to the international airport, is embellished with yet another infinite pattern. This time it’s the dodecagon star (left), another motif from the Seljuk period. There are also şemse-like traditional reliefs (right), at whose ends tulips appear. Such symbolism can be traced back to the Tulip Period of the Ottoman Empire at the beginning of the 18th century, taking its name from the excessive fondness of tulips among society’s elite. After the Empire’s military and diplomatic defeat in the Balkans, the flower came to represent beauty and hedonism rather than violent conflict, and was thereby linked to the peaceful foreign policy of that era. The application of tulips onto the Esenboğa Gate is thereby highly symbolic, not least considering the fact that the road connects the Turkish capital to the international airport, and consequently the world.

The Samsun Road gate looks similar to the gate of Istanbul’s Topkapı Palace, which was the royal residence of the Ottoman sultans for 400 years. Displayed on the new gate at Samsun Road, the star and crescent – a symbol popularised by Sultan Abdülhamit in the 19th century – now overlooks the traffic below.

The gate outshining all others, with its sorguç-like details in royal gold, is the one installed on Istanbul Road (right). It certainly pays homage to the Ottoman sultans portraying, for example, decorative kavuks – the shiny pieces of feathered jewelry worn at their courts. It is no surprise that sorguç details were selected for the road connecting Ankara to the city of Istanbul – the once-capital of the Ottoman empire.

In Ankara, public space – in this case highways – has become a playground for the authorities. With his towering gates, Gökçek now reminds each and every citizen of his power. This kind of behaviour may best be described as gigantomania: the passion, shared by the likes of Hitler and Stalin, towards constructing disproportionate symbols of power to be worshiped . Size is an obsession, as is the tendency to erect phallic buildings, or express immortality through the use of durable building materials. Gökçek has said that the gates were made from construction steel resisting to even earthquakes. The exercise of power over individuals in this way is not specific to Gökçek and AKP politicians. In the recent past, massive statues of Ataturk were erected in cities controlled by the opposition party CHP, like in Buca near Izmir and in Artvin.

Strategically constructing these gates in front of highways has resulted in a fetishistic obsession with modern conservatism, aimed at solidifying a particular identity with roots in a carefully interpreted past. All the gates point to a yearning in contemporary Turkey for heritage which, in turn, helps normalise the national identity promoted by Gökçek over time. Such zealousness may well be appreciated by Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, whose construction of the grandiose Aksaray Palace hardly can be diagnosed as anything but a similar case of gigantomania.