Geographies of war

Childhood recollections of a taxied escape from war-torn Beirut guide us through a geography reconfigured by conflict. How can memories of urban divisions traversed, snipers dodged and anonymous, altruistic compatriots encountered, re-narrate the Beirut of the civil war period?

I did not know Beirut until quite late into its long decade of pacification. I’d lived through the last spasms of war but, back then, my country only extended as far south as Antelias – or maybe Zalka. I would hear of “Beirut,” but only by name, as a concept or a character in a tragic play. “Beirut” was the battered damsel in a Majida El-Roumi song, pained but unplaced, and so it was fitting that my first visit a decade later was as part of a scavenger hunt, searching for trompe l’oeil in Downtown’s sandblasted streets.

I didn’t grow up knowing Beirut. In 1993, my family moved to the Gulf, but our drive to the airport was so unremarkable I have no recollection of it. In my mind, there’s a sudden change, a jump cut between one school – where a boy had shot himself in the playground, and the staff had gossiped about satanic music – and another, where a familiar language sounded foreign and I was confused for months. There must have been a point of passage, but there’s no trace of it left. In its place there is a much earlier drive to the airport, but in this instance the flight – the act of fleeing or running away, as from danger – is precisely all that is left, with no record of origin or destination.

The drive happened some time in the late 1980s. I know this because it was a year when two sturdy arms could swoop up and cradle me with ease. My mother and I were in a taxi of some kind. It was probably unsanctioned, like the thousands of black-plate cabs that kept the city moving when moving was not the norm. I like to imagine that our taxi driver eventually sold his car and is living comfortably somewhere, another nameless hero that no one’s thought to thank, though he doesn’t mind. Alternatively, he could still be out there, still moving people around in Beirut, but with a red plate on his taxi – one he’s hoping to eventually sell in order to buy an apartment, perhaps as a wedding gift for a grandchild. These are the more pleasant thoughts that come to mind as I think about that drive.

The taxi driver is now just another idea or character in a play. I’d only caught glimpses of the side of his face from behind, as I was too small to even see his eyes reflected in the rearview mirror. Yet, some aspects of that drive are burned more vividly in my brain: I remember the grey glow of morning reflected on the green interior. I remember the floor, and the smell of the rubber slip-guard that protected the carpeting from scuffs. I remember how cool the rubber felt on my face as I lied down in the gap between the front and back seats.

The driver had told us to take cover – there was a sniper somewhere up ahead. My mother crouched down in the nook beneath the dashboard and reached out to me through the gap in the seats, placing her hand on my back to reassure me. I don’t remember any panic, only acceleration, and in a blink we were at the airport with my mother sounding alarmed for the first time that day, as I was snatched up and pressed tightly against a man’s white t-shirted chest. That’s how I know what size I was that year. She needn’t have worried, though, because the man who grabbed me was yet another nameless hero merely helping us get inside as quickly as possible. I silently hoped my mother would catch up, but I don’t remember being afraid. Everything eventually decelerated, and so my memories now dissolve to black again, with no concrete understanding of why we were in a hurry in the first place.

We can piece together many narratives with these vignettes. Certainly, there’s a story of danger, hardship and personal trauma. This is the small-h history of a city trapped between “the light of a single burning match” and “the roar of the electrical generators”(1) and that’s archived inside us in mundane ways: when I first wrote down what I could recall of that da y, it became clear to me that there was a connection between that drive and a particular recurring nightmare I would have for many years.

There’s also a larger story of fragmentation, immobility and weaponised urbanism, as Karl Sharro explains.

[During a war] the city becomes a geography of violence in which its spatial structure is adjusted to the requirements of military control: tall buildings give a God’s eye view and reach for snipers, thus declaring the symbolic and physical supremacy of the militias; the network of bridges and tunnels built to connect the city are used, in a manner of speaking, to disconnect the city through the kidnappings and murders that nullify the functionality of the bridges. The physical structure of the city is functionally reversed.

We could populate this broader war narrative with (in)famous personae, like the Green Line, the Murr Tower and the Holiday Inn. This story is still inscribed in the flesh of our city. With every pockmarked building – still standing, still vacant – we are reminded of the brutal ways that Beirut’s “concrete city fabric” was entangled in “complex material and epistemological battles for the affirmation of different ideas about the Lebanese nation and territory”(2).

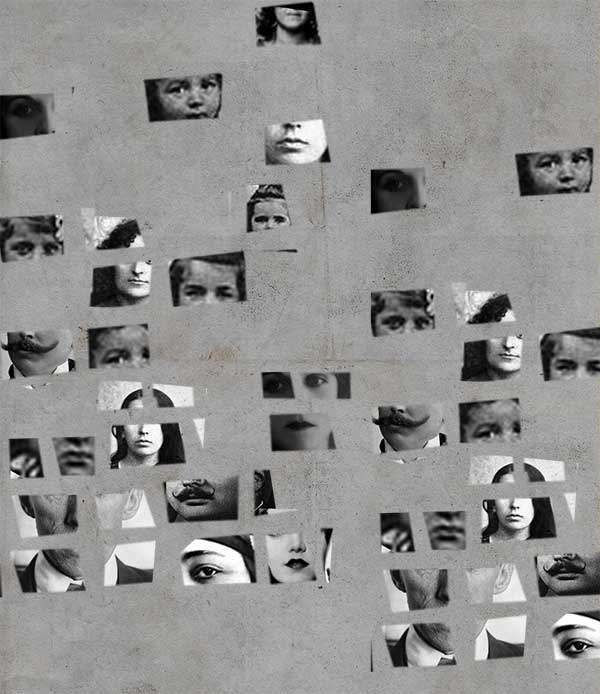

But what kind of story – indeed, what kind of city – might emerge if we were to reflect on the characters who left no traces in any archive, whose struggles were not attached to any major landmark or event, who neither battled nor resisted anything in particular? What if we based our narrative on the nameless characters who passed through memories like mine?

When I dig deep to try to remember more details from that taxi ride, I realise that what assured me the most was the taxi driver’s calm, methodical and authoritative voice. He knew what he was doing. He had done it before. Later, my mother told me that the driver had lowered his head and slammed down on the accelerator, driving blind, getting us through that alley where the sniper was perched. Imagine looking down through a sniper’s scope and seeing our phantom vessel defiantly rocket past. The taxi driver’s skill highlights, for me, the political implications of our war narratives: to represent a city from the perspective of people like my mother and me, crouched and in flight, reveals one sort of Beirut, but there’s another Beirut there too.

On the one hand, we have a Beirut that’s split in two – a “divided city” like Belfast or Berlin – and a city centre, once “celebrated as a meeting ground for all Lebanese,”(3) that is lost, irreversibly, it seems. On the other hand, we have sniper alleys that can be crossed, if you know how to cross them, and a demarcation line that was always multiple – remember: there’s no actual Arabic equivalent for the term “Green Line,” only khutut al tammas, which means, more accurately in plural, confrontation lines(4).

This is the Beirut that hurried us along, that got us through, that maintained coherence among the fragments and that resisted the functional reversal of the city.

When we emphasise cloistering over crossing, division over porosity, trauma over resilience, consumption over production, we thicken that so-called Green Line in our imaginations and transform Beirut from a city negotiating divides into yet another divided city. But what did our city look like from the driver’s seat?

I cannot pretend to know the city that our driver knew, but I can hold on to my memory of him, and to what this memory means to me, as I reflect on my own drives to the airport. After all those years, after that particular wave of warring had ended, there are no more snipers to dodge, and I am no longer cowering in the back of the car. I am the one in the driver’s seat, and yet I cannot help but feel that my drive to the airport is still elliptical, and no less hurried along. When I drive to the airport, there are still gaps in my narrative, except that, this time, these gaps are by design. The road I take – this highway we call taree’ al-matar or al-autostrade al-sare’e – seems made just for me, a cocoon of convenience rolled out before me as I take flight again and again.

Is this the work of a good Samaritan?

No. It’s a trick of the eye. Through its tunnels, its bridges and its concrete walls, the airport road is forcing me to look away from the neighbourhoods that I slice through and the public square that I gracefully glide over and erase.

I am out, and I am safe. I can share my story. I can narrate my city. Here we are, reading it together.

But what about the city under the bridge? How many nameless heroes work down there, at the intersection we call Cola? The intersection we call Dora? I want to see their city archived. I want a record kept.

1 Saghie, Transit Beirut, 2004:117.

2 Fregonese, “The urbicide of Beirut? Geopolitics and the built environment in the Lebanese civil war”, Political Geography 28, 2009:309-318.

3 Sharro, Warspace: Geographies of conflict in Beirut, 2013.

4 Moystad, Morphogenesis of the Beirut green line: Theoretical approaches between architecture and geography, 1998.