Fueling Turkish feminism with satire and humour

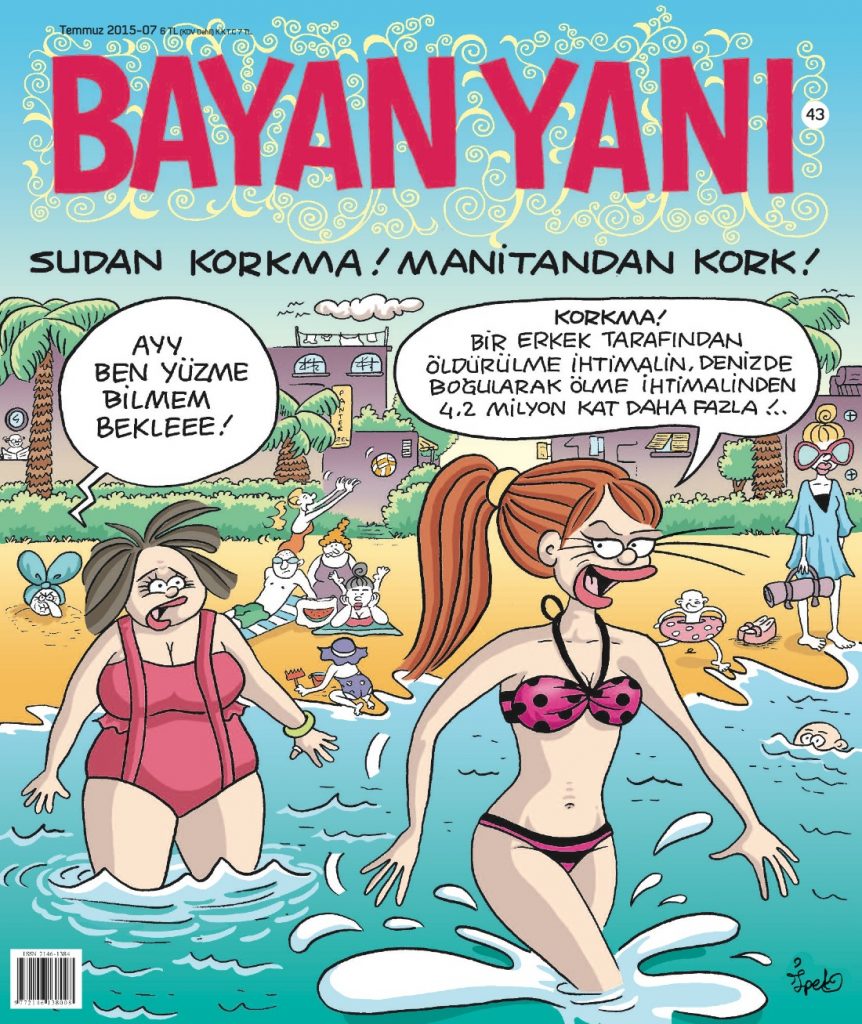

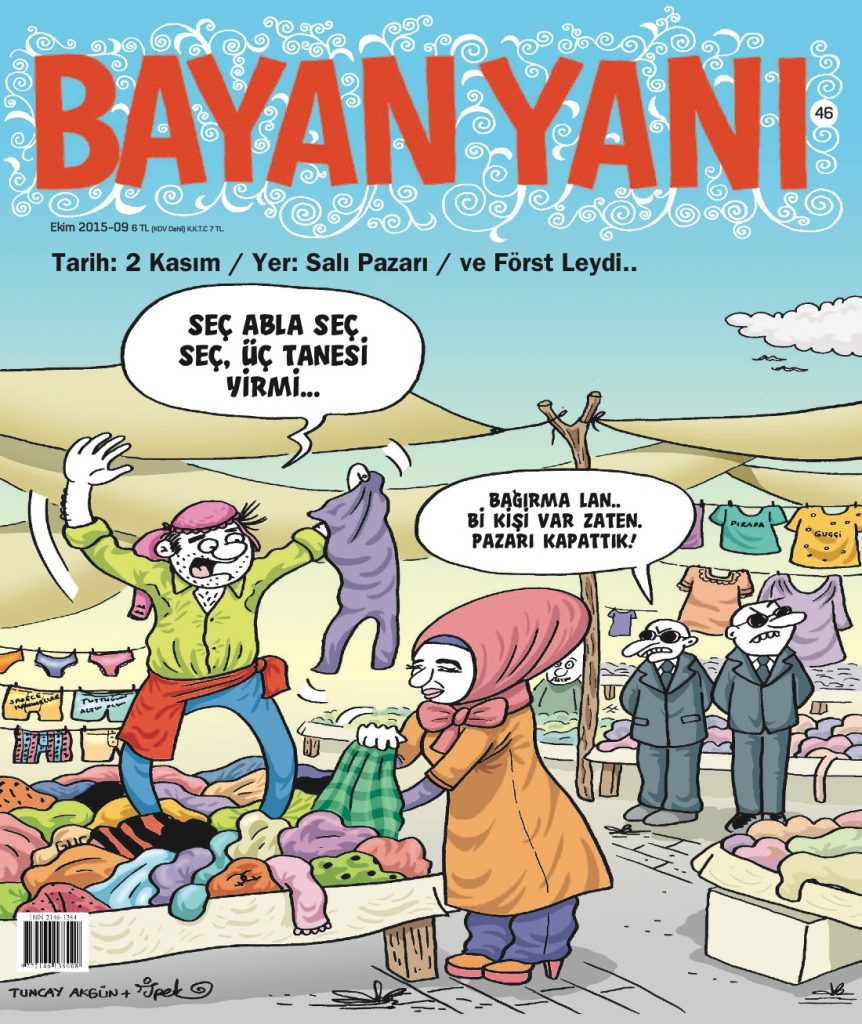

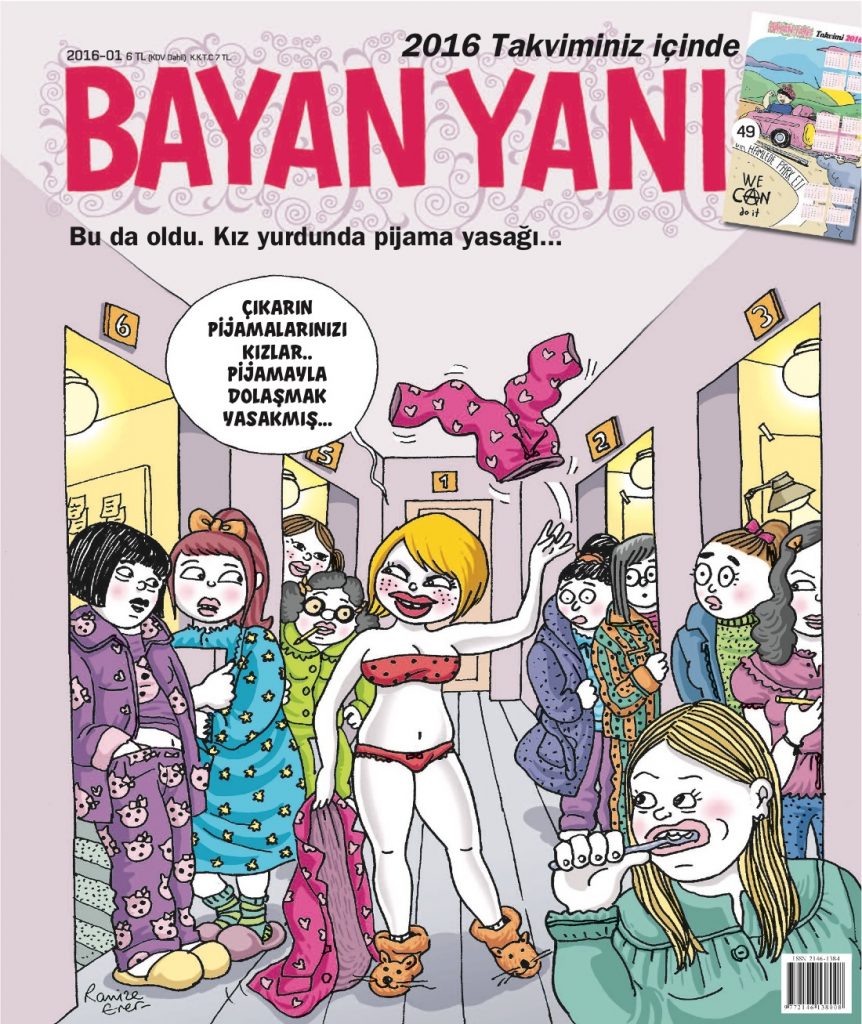

Bayan Yanı is a satirical magazine led by women in a country which is becoming increasingly hostile to them. For more than six years, cartoonists and writers in Turkey have combined their talents to make readers not only think but also laugh in a feminist way.

It takes at least one hour to reach Avcılar by public transport from Istanbul’s city center; the district lies on the western side of the huge Turkish metropolis. Before undergoing swift urbanisation in the past decades, Avcılar, which is one of the 39 districts of Istanbul, was a small village on the Marmara sea coast. Significantly, it is the only one where a woman was elected a mayor in the most recent local elections. Unlike other sleepy suburbs of Istanbul, Avcılar is a dynamic place thanks to one of the Istanbul University campuses being located there, and has a big pedestrian avenue lined with plenty of cafés, shops and restaurants. Ahead of the big constitutional referendum taking place in Turkey on 16 April, Avcılar’s main avenue has also been a place where activists have put up and congregated around white tents campaigning for either Yes (Evet) or No (Hayır). If approved, the referendum would grant president Recep Tayyip Erdogan even more power.

Avcilar is also home to Ezgi Aksoy and Feyhan Güver, both taking part in and spearheading a unique media endeavour: Bayan Yanı, a satirical magazine publishing only women cartoonists. “It all started in March 2011 as a one off issue,” recalls Aksoy. “We gathered writers and cartoonists already working for the more general satirical magazine Le Man [one of Turkey’s three top satirical magazines, along with Penguen and Uykusuz]. We wanted to print a special magazine for the International Women’s Day, because at this time women’s rights were starting to become under threat in Turkey. We made the first issue and decided to continue after receiving feedback encouraging us to do so.”

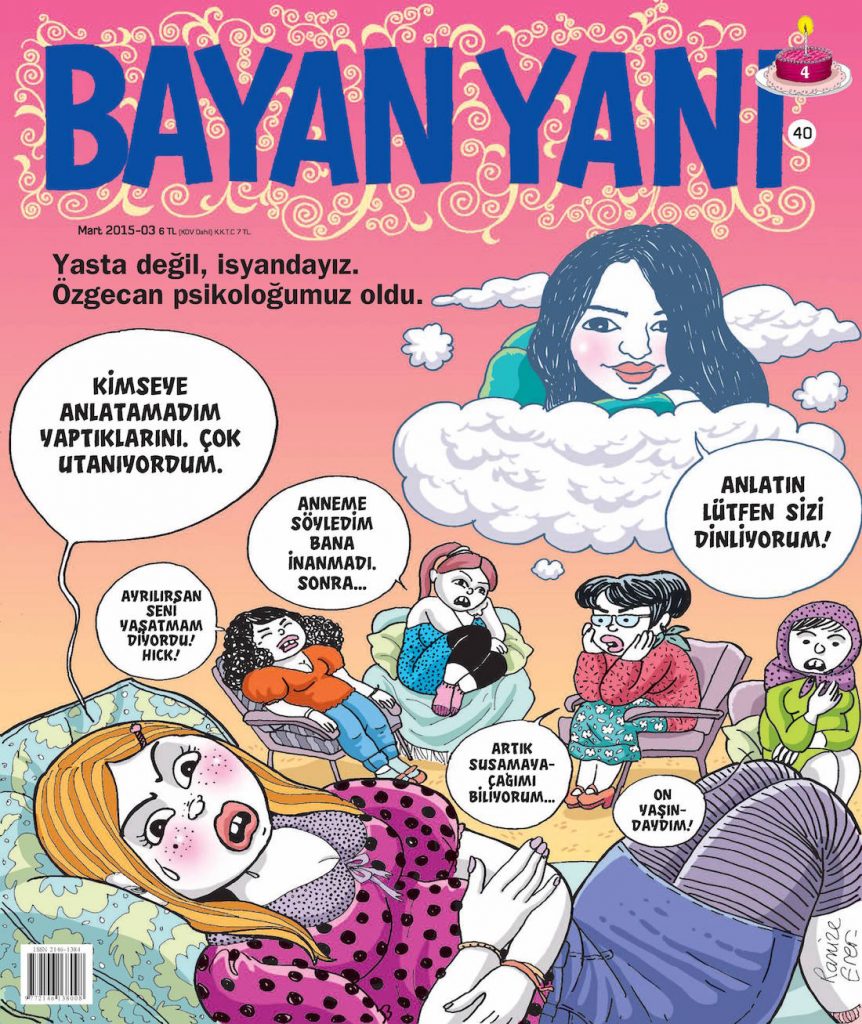

It has now been six years since the launch and Bayan Yanı has published a new issue each month. Each has dealt with the country’s endless political turmoil and its daily life troubles, including things like hate speech against women, domestic violence and murders of women. For the magazine’s contributors, it is hard to disconnect the two.

The magazine is called Bayan Yanı, which could translate to “Women side by side”, poking fun at a peculiar form of sexual segregation

Aksoy is a freelance writer, specialising in cinema and Latin America. In the March issue, she wrote a portrait of Berta Caceres, an environment activist from Honduras who was killed last year. Güver is a cartoonist and a long-time contributor to Le Man. She likes to draw stories about relationships and friendship, typically set in the small village in the region of Thrace, where she is from.

The magazine is called Bayan Yanı, which could translate to “Women side by side”, poking fun at a peculiar form of sexual segregation occurring in Turkey, says Aksoy. “If you are not relatives or friends, inter-city bus companies forbid women and men sitting next to each other.” She explains that when the team started their project, there was a news article about a woman who wanted to buy the last remaining seat which would have seated her next to a man. “The company did not sell her the ticket. This rule is quite funny because it does not apply to other forms of transport such as planes or local buses”.

While Bayan Yanı is primarily a women’s stronghold, its editorial board also has one man publishing regularly on its pages: satirical writer Attila Atalay. “He writes about a female character, but he writes so well that no one would think it is the work of a man”, says Aksoy. The magazine is the work of a fluctuating collective of contributors. “We are free to publish what we want, there is no boss. We just exchange emails with our ideas,” says Feyhan.

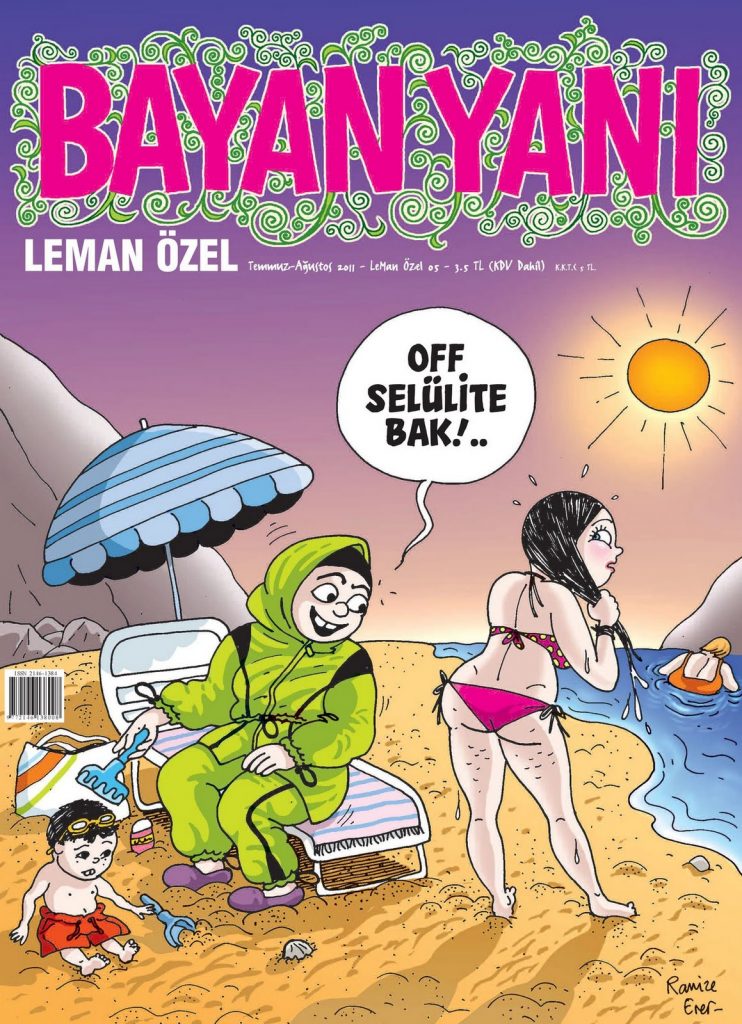

Bayan Yanı has a core group of six or seven regular contributors, all located in different parts of Turkey and even abroad, such as cartoonist Ramize Erer who lives In Paris. The last issue had a four-page long comics story where Erer describes how her most iconic characters came to life. There is Nadide, a seemingly happy wife who represents what Erer calls the “modern” or “enlightened” face of Turkey. There is also Ezik, her more traditional counterpart, who is ill-treated by her husband; and Berna, an assertive and independent character, always breaking social taboos and conventions, who in the comics go by her Turkish nickname kötü kız, which means “bad girl”.

“Going to jail is not a faraway possibility for any of us”, says Aksoy.

Berna is blond and curvaceous; other characters in the magazine are tall, thin, young or old, coming from both urban and rural backgrounds; they are veiled or unveiled, fashionable or hopelessly untrendy. Unlike in other women’s magazines, those in Bayan Yanı have very diverse bodies and personalities. “Women tell us they feel more comfortable with our magazine because of this reason,” says Güver. “For example, our cartoonist Ipek is very tall and she addresses the difficulties of being tall in her work.”

Each story and character may deal with both lighter or heavier topics, explicitly covering more or less all issues affecting women: discrimination, machismo, social pressure, rights and struggles. In the initial pages of each magazine, many illustrations are dedicated to the latest news and scandals related to gender. The violence perpetrated on women, which is otherwise normalised, becomes absurd and unacceptable under the pen of Bayan Yanı caricaturists. Both world leaders or national politicians are usually not depicted in a positive light; countless illustrations, for example, highlight and address Erdogan’s misogyny. “It’s important to be humorous, because it gives us more impact,” says Güver.

Aksoy highlights that Bayan Yanı writers have differents worldviews: some are more liberal, others are Kemalist or supportive of the Kurdish movement – all fighting the current Erdogan regime. “In general, we are of course closer to the opposition”, she says.

Whether they are hard or soft, most opposition voices are having a hard time under Erdogan’s iron rule. In the recent months, and especially after the failed coup attempt of July 15 last year, repression has increased, and dozens of media houses have been closed. Turkey currently holds the world record of being the country with the most journalists in jail, having around 150 media workers behind bars. Musa Kart, a caricaturist from the newspaper Cumhuriyet, one of Erdogan’s most disliked publications, is incarcerated under harsh conditions in Silivri, a huge prison built on the western edges of Istanbul; in fact, it is not far from Avcılar, where Aksoy is living.

“Going to jail is not a faraway possibility for any of us”, she admits. While the Bayan Yanı team has not yet faced any lawsuit or pressure from the state, the case was different for Le Man. “After July 15, a group of people came to the publisher’s office at night and brought a jerry can of oil, threatening to put the building on fire. There was fortunately no one at that time in the building, otherwise who knows what could have happened to our friends?”

The cover of Le Man’s issue following the 2016 coup attempt angered Erdogan’s fans: at the very same time that the small crowd attempted to set fire to Le Man’s office, the police actually went to its printing place to stop the magazine’s distribution.

When asked about censorship, Aksoy answers: “You start to implement self-censorship without noticing. I stopped writing editorials for a while. If you write something that is considered insulting, you can be sentenced to jail.” Güver recalls that once, after having made a caricature of the president’s wife, Emine Erdogan, she first thought about “softening” it but eventually decided against publishing it at all.

Bayan Yanı has a strong readership community, with more than 360,000 fans on Facebook. “We have bonds with many of our readers, Bayan Yanı is part of their lives. If we are a bit late with an issue for example, they always message and ask when it will be released,” says Aksoy.

Against all odds, Aksoy and Güver are committed to making the magazine’s voice heard and intend to produce it as long as possible. Their most recent April cover deals with the ongoing referendum, mimicking the popular pictures people have been taking of themselves forming the Turkish word “Hayır” with their bodies, favoring the No vote. On it, the magazine’s diverse characters stand next to each other, expressing a collective “no”. Indeed, a Yes vote in the referendum would change Turkey’s current parliamentary system to a presidential one, something that undoubtedly would reinforce conservatism and affect individual freedoms for Turkish citizens – certainly not good news for Bayan Yanı’s combative cartoonists and readers.

This article is part of the Web Arts Resistances project and platform coordinated by Babelmed in collaboration with Inkyfada, ONORIENT, Radio M and Tabasco video.