Kasserine

Addicted to the polluting plant

A paper plant has been polluting the air and water of Kasserine, Tunisia’s water tower, for almost fifty years – without anything being done about it. Pollution control projects would cost too much, and no one can touch the largest employer of the region.

From their terrace, the Saadaoui family has a commanding view of the paper mill, It is only a stone’s throw away. Their neighbourhood is on the edge of the small El Khadra Development and is growing ever closer to the factory. The Cellulose, as it is called here, has almost become a family member; an endless subject of anecdotes. Ahmed, the grandfather who worked for the factory for thirty years, has a favourite: that of the chlorine leak of 1983.

“Around 11pm, a chlorine cloud arrived, a meter high. My sheep started coughing, so I went around the factory with them to escape the smoke. The neighbours left in their cars and went as far as they could, because they felt the chlorine on their clothes. They thought they were still in the cloud.” Ahmed still chuckles when telling the story. Back at his house, the banknotes of in the family grocery store were all turned yellow by the chlorine; the coins took on a greenish colour. Everyone in the neighbourhood was treated to a hospital visit and those who filed a complaint were well compensated.

An environmental aberration

Compromise has sustained Kasserine for fifty years. The Cellulose continues to poison the daily life of the neighbourhood, yet it remains an untouchable institution: it is the largest employer of this rocky, desert region, one of the poorest in Tunisia. The National Society of Cellulose and Alfa Paper (SNCPA) is an industry leader, a “strategic investment” which dates from 1963. In a region where unemployment has reached over 20%, this plant plays an important role, giving work to 800 employees – as well as hundreds of farmers of alfa, an herbaceous grass which abounds in the hills around the plant.

The alfa paste produced at Kasserine is exported to France, Europe, North America, China and Japan. It is used to make high-quality paper, as well as cigarette paper. Until recently, Philip Morris was one of the factory’s principal clients. It also produces hydrochloric acid and sodium bicarbonate, which are necessary to bleach the alfa paste. Archaic outmoded, the paper mill has become an environmental aberration – and a danger for the population.

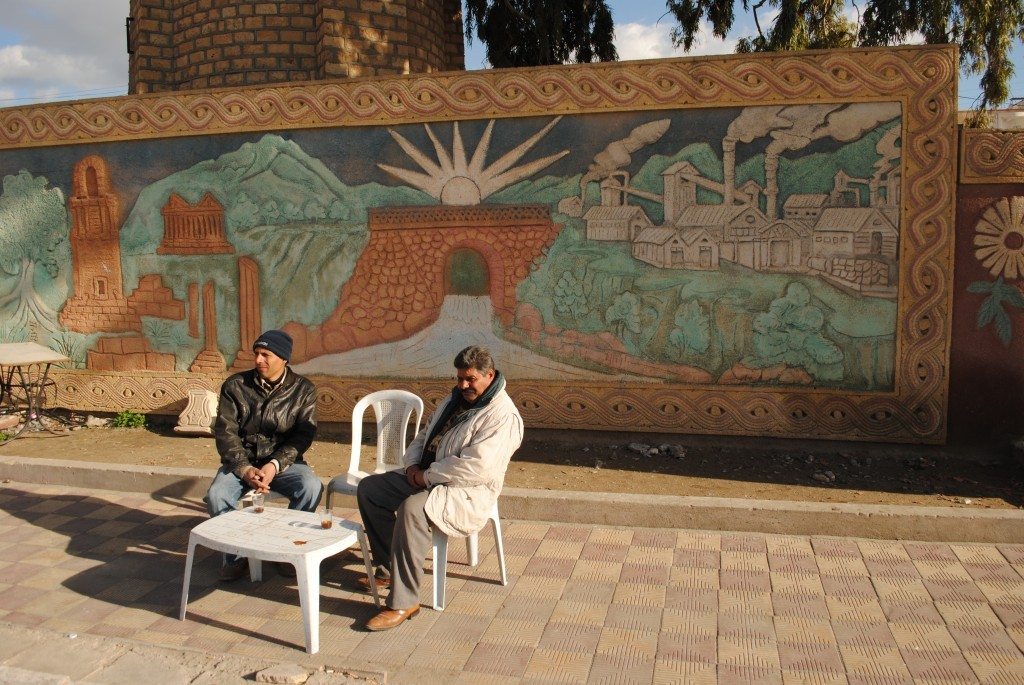

The local cult organised around the factory – a sculpture to the glory of the alfa plant, a Soviet-style fresco downtown – has been cracking for a while. The revolution accelerated things – Kasserine The Rebel paid a heavy price with 21 dead and 400 wounded in last year’s uprising. Now, the factory’s neighbours no longer hesitate to file a complaint against the mill and have begun to protest against the chlorine leaks, which have become commonplace.

In 2009, 87 inhabitants of the green city were poisoned. The last leak dates from two months ago. To Maher Bouazzi, the young mayor and a lawyer himself, the lawsuits are reasonable. “The factory is ruined, completely damaged. The leaks come every two or three months. It’s catastrophic.” He has a theory: “Under Ben Ali, the SNCPA purposefully didn’t maintain the factory. This way, they could privatise and fill their pockets.” As a lawyer, Maher Bouazzi has “three dossiers on the chlorine” awaiting a trial. Between 6% and 9% of his clients have physical disabilities.

Chronic illness

People in neighbouring cities breathe air polluted by the smoke from the paper mill. Sometimes this smoke is white, sometimes yellow or black, depending on the activities of the plant. Elyes Hassin is the only lung specialist who comes to Kasserine from Tunis. Every Saturday, outside of his regular hours, he examines about 120 patients. His diagnosis reports the following: “People who live in these zones are all victims. They complain of the odour and of the smoke which makes them cough and gives them a dry mouth and stuffy nose.”

From his work with the people affected by Kasserine, he can recognise the sicknesses caused by the surrounding air. “It includes all kinds of respiratory problems and irritations, including rhinitis and sinusitis,” he says. Because of continued exposure, the problems become chronic: in the region bronchitis lingers, coughs persist and asthma attacks worsen.

Without knowing the exact composition of the smoke, Elyes Hassin can only make an educated guess based on the activity of the mill. His list is long: sulfur derivatives, ammonia, oxide and nitric oxide, carbon monoxide and carbon dioxide. It is also impossible to determine the ratio of sick to healthy people: no such studies have ever been conducted. Why? “No one is interested in Kasserine. I only come here because I’m a child of this land.”

The dry river that runs along the green city is the source of additional pollution. It is there that the factory continues to dispose of its wastewater, without any preliminary treatment of the river. Three pipes lined with a dubious sediment spit up a whitish liquid in the wadi, which continues to Sidi Bouzid, one hundred kilometres away. “The water has been coming out that way for 45 years,” says Ezzedine Msakn, a 63 years old resident of El-Khadra. He remembers that the prime minister came to inspect the damages in 1972.

“The water discarded by the plant has never been analysed because the authorities want a dependable expert,” claims a specialist of water hygiene for the Minister of Health, who worked at Kasserine from 1992 to 2006. The wastewater in the river is that which was used to treat the alfa. According to a factory worker, it is loaded with hydrochloric acid and sodium bicarbonate, the products used to bleach the paste. One thing is certain about the Kasserine water, says Sghouer Debbabi, district chief of the National Society for Water Operations and Distribution (SONEDE): It is polluted and dangerous. Even the sewage treatment centres are incapable of handling it.”

Flocks of sheep decimated

Two water treatment projects have collapsed. In 1967, a treatment station was built in front of the factory, operated for a short period of time before being shut down due to the odour. It has since become a garbage lot where goats graze, situated right next to the Saadaoui family’s terrace. The second attempt was initiated in the mid-1990s when the factory was linked to a city water purification station. The National Office of Sanitation (ONAS) installed a meter to measure the quantity of treated water, for which the factory was billed. It was feared that ONAS was inflating the numbers to make additional profits. This was yet another failure.

The environmental risks of the waste are considerable, especially since the region of Kasserine is the most important water tower of Tunisia, with 270 million cubic meters of groundwater in reserve. Necid Hadj Larbi, director of the Regional Commissary for Agriculture Development (CRDA), confirms that the severity of the pollution limits regional agriculture: “We educate farmers along the river, so that they don’t grow vegetables – olive trees at most.” Stories abound of flocks of sheep being decimated after having been led to tainted water. He also claims to have asked the factory to pre-treat the water they dispose. “They have done nothing so far. They must first find the funding.”

Mercury pollution

City authorities, led by SONEDE, remind people that tap water is clean and safe to consume when drawn from a depth of about 700 meters and treated accordingly. Nevertheless, doubts hang over everyone’s head. Until 1995, the factory used mercuric electrolysis to produce the chlorine and bicarbonate applied in the treatment of the alfa paste. Ahmed Saadaoui, who manages the stock, confirms that each month, three to four 50-kilo barrels of mercury were used in the electrolysis process and that leaks of the heavy metal were common.

“Very little mercury was disposed of,” clarifies an official at the Ministry of Environment. In 1993, the quantities of mercury found in the water of the wadi were 375 times greater than European averages, according to a report from the Ministry of the Environment. Since then, however, “we have not found any trace of mercury in the drillings,” insists a Ministry of Health official. The mayor of Kasserine is not comforting: “I don’t drink the water here, only the poor people do. I drink mineral water.”

“The problem with the factory is the safety”

The first people to suffer as a result of the factory’s poor conditions were the workers. A qualified technician, who works at the paper chain, explains that he earns 800 dinars (400 euros) monthly, a good wage for the region. But he worries for his safety and that of others. “The worst comes to those who work next to the electrolysis.” He confirms that these workers do not wear a mask or coveralls “except when there are leaks. Last month, four workers suffered burns and respiratory problems.” According to another worker, “the problem with the factory is the safety; there’s no money for that.”

At the SNCPA headquarters in Tunis, the administrative director, who is also the human resources manager, is made visibly uncomfortable by questions regarding safety. When the chlorine leaks are brought to his attention, he declares, “There have never been any chemical accidents.” When faced with the 87 cases reported in 2009 in El-Khadra alone, he quips, “You’re teaching me things!” He cuts short the questions about the factory pollution: “It’s a situation of which I’m aware, but I cannot answer your question.” His boss, the CEO of the SNCPA, has not responded to requests for an interview.

A political hot potato

For public agencies, the factory is not a priority. Since the issues are social, industrial, environmental and sanitary, the hot potato is passed back and forth with no solutions. The SNCPA is supervised by the Ministry of Industry, which reports to Hajer Bouhlel, the regional director of the Agency for Industry Promotion in Kasserine since 2004. According to her, “if there is a pollution problem, the person responsible at the factory or the Industry Ministry must be notified, and I believe that there would be no problem investing in pollution control.” About the leaks, she is emphatic: “The chlorine causes asphyxia and there are no cases of asphyxia at Kasserine as far as I know. There is smoke, of course; I can’t deny it.”

Mayor Maher Bouazzi, who has been in office for 11 months, understands that he is overwhelmed by the problems related to the factory. He claims to have alerted the ministries of Environment and Industry in September 2011, just before the government changes in November. He assures that he spoke with the director of the factory. “I hope there are sanitation programs,” he says. The SNCPA will not comment on any upcoming projects, but a worker believes that they are seeking solutions for the defective fuel boiler and that certain parts of the electrolysis will be changed in a month from now to remedy the leaks. Even during this period, however, the factory will still be in operation, thanks to stockpiled materials.

Elyes Hassin, the lung specialist, confesses he is distraught. “At the end of 2012, after the elections, we’ll know what to do.” He recommends the formation of a committee of specialists, doctors, experts, engineers, meteorologists and statisticians. “If the Ministry of Health doesn’t take care of it, it’ll be the role of the NGOs.” Deep down, he understands the prevalent inertia. “We’re all used to the factory, and it doesn’t seem very threatening. So we don’t talk about it. It’s a form of compromise. It is the livelihood of everyone here, including myself.”

Written by Benoît Berthelot and first published by Medinapart.