Queer film fest touring Turkey

Talking to director Esra Özban

For the eighth year in a row, Turkey’s queer film festival KuirFest sets off on a mini-tour to two smaller Turkish cities. KuirFest, which is run by the organisation Pembe Hayat, founded by trans women and sex workers in Ankara, reaches Denizli on March 30-31 and Mersin on April 27-28.

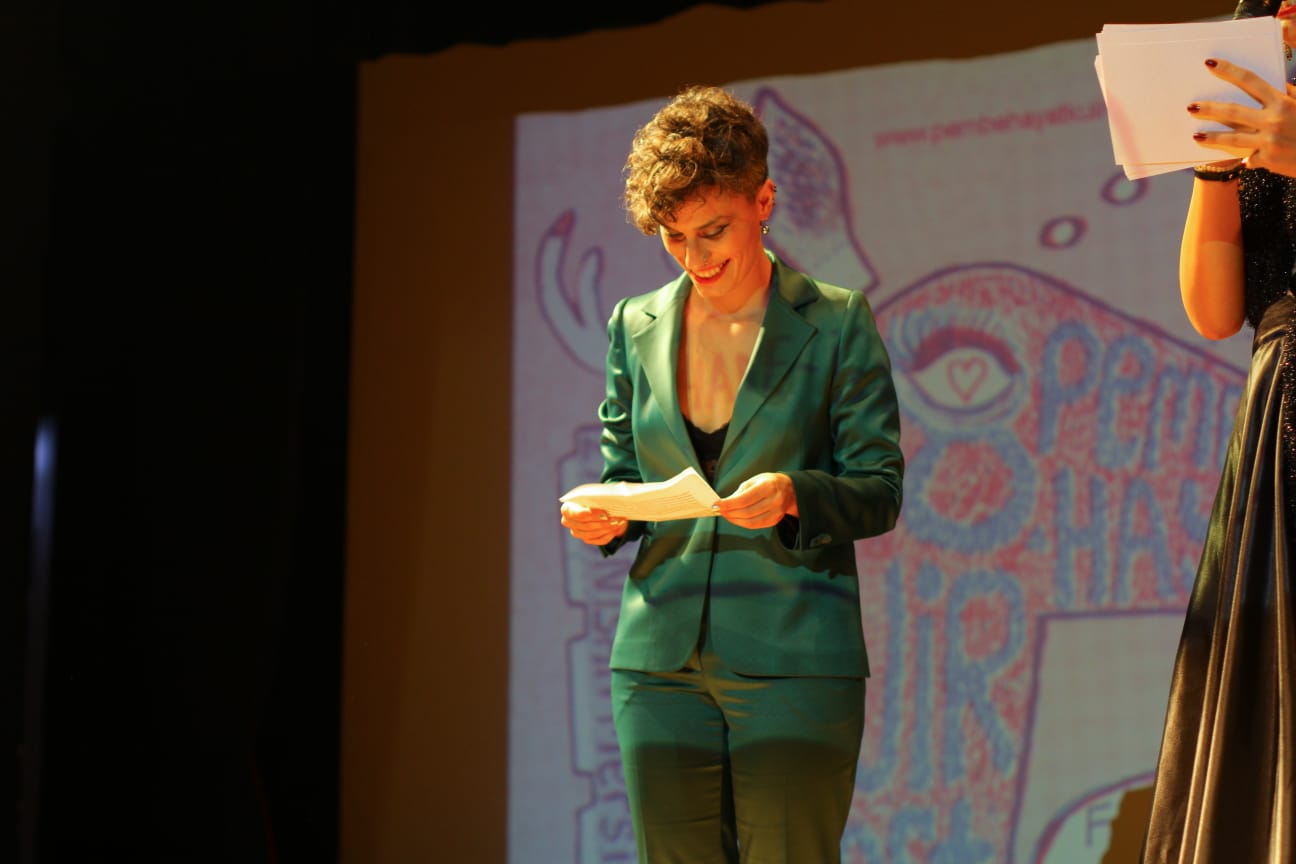

The festival opened in Istanbul in January – the first time KuirFest came to Turkey’s largest city – following a ban on public LGBTI+ events in the capital Ankara. The ban, first imposed during Turkey’s state of emergency in 2017, has not been lifted, and a new internet censorship bill passed by parliament in March 2018 further curtails freedom of speech. As KuirFest travels to Istanbul, Denizli and Mersin, it is headed since two years back by director Esra Özban, a screenwriter, media scholar and academic specialised in feminist theory. We met with her in Istanbul to talk about this year’s festival.

Could you tell us about the trajectory of KuirFest so far?

The festival started in Ankara in 2011, where it stayed for the first three years and contributed to changing the cultural and queer community scene in the city, because most things happen only in Istanbul. In the festival’s fourth year, we started going to Istanbul as well, and for our fifth and sixth festivals we traveled to other cities too. That is how it grew.

No one expected a queer festival to emerge from Ankara, but that was, let’s say, a queer move. KuirFest is a place for everyone, where each person can find something for themselves. It is an important gathering for most of us. We want to really gather the community, not only those in Turkey but friends who have moved from Turkey as well.

No one expected a queer festival to emerge from Ankara, but that was, let’s say, a queer move.

We are curious about Mersin and Denizli, why did you decide go to these cities?

For the last four years we have brought the festival to Mersin and Denizli, two very special cities. We always collaborate with local organisations in each city we go, and in Mersin it started like that. It has been historically important for the trans community, and has a really strong movement. There is an activist community and a big queer scene there, and KuirFest is just one of several events Pembe Hayat holds in the city.

Denizli is special because it has become a hub for Iranian LGBTI+ refugees. There is a law in Turkey regulating the so-called “satellite cities”, where many refugees are assigned to live. Only Syrian refugees can travel and settle anywhere in Turkey, others, including LGBTI+ refugees from countries like Iran and Afghanistan, must live in these “satellite cities”. And this is the case with Denizli. Last year, we started to subtitle all films screened during the festival in Farsi.

While it has been impossible to organise a Pride march in Turkey since 2015, you have been able to run this incredible multi-city film festival. What challenges are similar or different for you both?

Of course there are different challenges, because these are different things to organise. But overall, it is not easy to organise official LGBTI+ events. Pride is officially banned, and all LGBTI+ events in Ankara are as well. Sure, we held the opening of this year’s festival in Istanbul, but we are based in Ankara where everything is banned. That is really a huge challenge.

Still, queer movements are not only about official gatherings and events. We are a community, we do a lot of stuff. Even if they ban Pride, there will still be small Pride marches on tiny streets. There are a lot of Prides taking place all over Istanbul. And it is important to see not only what we are doing today but also what people did before us, what their strategies were. Because times have changed. We have a lot of associations now, but we still have challenges.

And yes, we are a multi-city festival, but we are a very small team and a very small festival if you think in terms of arrangement and not in terms of content. We usually have three to four people – this year five people – working with the festival, that’s all.

Overall, it is not easy to organise official LGBTI+ events. Pride is officially banned, and all events in Ankara are as well.

Why do you think the decision came to ban all queer events in Ankara?

These bans are justified with things like with upholding moral standards, or security. But neither moral nor security could be a reason to ban all events related to LGBTI+. We are not a threat. And by the way, I don’t want to say that we are not immoral. We are immoral and we love it [laughs]!

How do you select the films screened in the festival, and how do you find a balance between Turkish and foreign films?

We would like to show more films from Turkey, but there are no more! That’s the problem. For a couple of years, we had no shorts from Turkey, because we did not find films that we wanted to screen. They were either too victimizing or hetero-perspective – this was the case with films about trans sex workers for example – or there was something else that we could not stand behind.

In the last couple of years, we have tried to focus on supporting the production of queer films in Turkey. That is why we organise a lot of workshops in things like smartphone filming, stop-motion animation, editing and scriptwriting. KuirFest was always more than just a film festival, we have always held plays, exhibitions, workshops and panel talks. This year, there is a queer performance with [choreographer and dancer] Gizem Aksu, who is doing a lot of great stuff in Turkey. We want to collaborate with artists and filmmakers, especially those who belong to the community and want to contribute to it.

I don’t want to say that we are not immoral. We are immoral and we love it!

You choose to show Atıf Yılmaz’s 1994 film The Night, Melek and Our Children, set in the darkest streets of Istanbul’s Beyoglu district. How come?

Whoever is interested in cinema in Turkey – or not even interested in cinema, but likes to watch films – has crossed paths somehow with the movies of Atıf Yılmaz. He is one of the very big names, and he made many powerful films about women. That’s how he is mostly known.

His film The Night, Melek and Our Children is important because it portrays queer society in the 1990s, just as it was during that time. It is about sex work, and many characters speak the queer slang lubunca. It is a powerful film and we are really happy to screen it this year, which is its 25th anniversary.

What does lubunca mean, can you explain?

It is a slang commonly spoken across Turkey’s queer communities, most of all as a tool to communicate. If you are surrounded by police for instance and want to say something to your friend, you use lubunca to say it in way so that they won’t understand.

We would like to show more films from Turkey, but there are no more! That’s the problem.

This year, the festival focuses on textile workers. Who will speak?

We don’t mention the names of the speakers because of security reasons. One of them is from Denizli and has been a textile worker there: this person is a migrant and that is why we try to keep them safe. Their experiences are quite horrible. Then there is another person too, who is from Turkey and has a lot of experience in the textile industry. We will look at different experiences in the industry and what happens when you are queer or a refugee, or when you are a queer refugee.

It is interesting that you are screening a film by Thai director Anucha Boonyawatana, the second time that you feature her work. KuirFest has a broad outlook.

Yes. We try to be as broad as we can geographically, even thought event wise it is hard for us to bring someone from Thailand for instance. The film we are screening from Anucha Boonyawatana is Malila: A Farewell Flower from 2017.

We have worked hard to include more films from North Africa, Middle East and Southeast Asia. Last year, we brought two films from Armenia to the festival and did a special focus, including a panel, on Armenian LGBTI+ cinema. This was to learn about their struggles and what is happening in Armenia.

We want to collaborate with artists and filmmakers, especially those who belong to the community and want to contribute to it.

That is interesting. Before we end, is there anything else you would like to add?

Yes, I would like to talk more about the challenges. We have talked a lot in Pembe Hayat about how we can proceed with the festival after the bans. It is quite arbitrary what they will ban and not ban.

After the ban in Ankara, there was a campaign saying that LGBTI+ in general cannot be banned, and queer films cannot be banned. We got in touch with film directors and asked them to share the hashtag against the ban, and we shared previously screened festival films on our Facebook and Vimeo channels. That way, we reached an audience that had seemed almost impossible for us before, some 20,000 people watched these films.