Sharing the art

Speaking to Suzee in the city

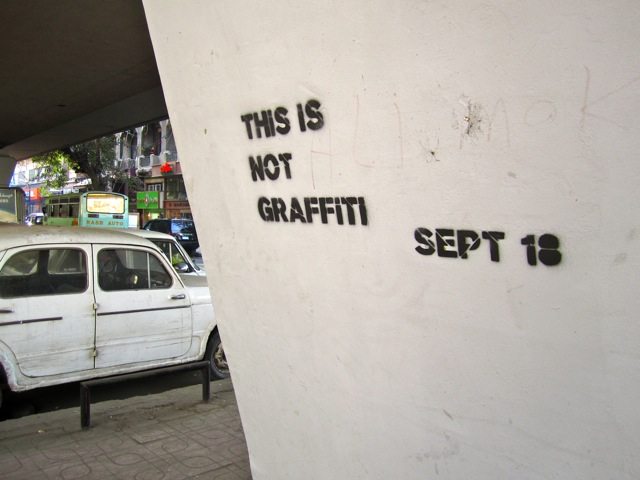

Following the start of the revolution one year ago, the streets of Cairo and other Egyptian cities have seen a growing and dynamic movement of political art in the streets. For anyone interested in the work of the artists, there is one place to go (except for wandering the streets, of course): Suzee in the City. Her blog gathers anecdotes, interviews, and online galleries with graffiti pieces — many of which have been erased or removed from the walls. She was also the curator for Townhouse Gallery‘s exhibit This Is Not Graffiti, the first of its kind in the country. Mashallah News spoke to her about the fascinating post-January 25 mix of art and politics in Cairo’s streets.

Since last year, your blog has grown into a great resource for the dynamic street art movement in post-Mubarak Egypt. How did it begin?

I’ve always loved graffiti, and photographed it whenever I travel outside of Egypt, and I was disappointed that the urban culture of Cairo, Alexandria and other big cities in Egypt didn’t include graffiti, or at least the sophisticated street art scene that is common in the West. The street art that was made in Cairo and Alex was done by a small group of artists who worked undercover. Many of their pieces were removed the next day, and some of them would get into trouble with the police or people for making graffiti. So the fear barrier prevailed.

“Pretty much all of the artists were involved in the revolution somehow and are politically active. Almost everything they make is political or has political nuances.”

Then the revolution happened, and graffiti grew with the demonstrations of Tahrir Square and other parts of Cairo. It was almost synchronised with the revolution in its development; more people joined as more attention was given to the scene, and the graffiti became more sophisticated and defined in its structure, style and message. I was lucky enough to live in an area of Cairo that constantly witnessed new graffiti. When I noticed that many graffiti pieces were being removed and erased, I decided to photograph them and document them in order to have an archive of these amazing pieces of street art. Luckily, other people were equally fascinated, and I think that there is now a comprehensive collection of photographs of all the graffiti that has been made since the revolution.

That is how your documentation of street art started?

Yes. It was a very organic process. When I made my blog, I circulated it to friends, who passed it onto theirs, and somehow it reached the graffiti artists that I was following or their friends. Some artists contacted me to tell me about their work or to send me photographs of their latest pieces. Others I met by coincidence; simply by walking by as they made graffiti or by meeting them through common friends. The ones that I have met are all very young, very interesting people who are easy to get along with. I think they understand that I appreciate graffiti and what they do, so they let me observe them when they work and tell me about upcoming projects.

There are very few women working in graffiti, only Hend Kheera and Aya Tarek as far as I know, the rest are guys. Their young age is a very good reflection of the majority of the Egyptian population, which is between the ages of 18 and 25. And pretty much all of the artists were involved in the revolution somehow and are politically active. Almost everything they make is political or has political nuances, except for a few artists.

“Blatant pro-army or pro-government art belongs to Mubarak’s time, where the only art you’d see on the walls was election posters, or advertisements, or praise for Mubarak and the army.”

So many of the artists come from a similar position in terms of outlook and message?

I think they do in so far as they’re opposed to SCAF. I’ve yet to meet a graffiti artist that’s praising SCAF. They do exist, but they’re not artists in the sense that they will put time and effort into cutting a stencil or creating a mural that can take hours to complete, all for the love of SCAF. I’ve seen some graffiti, just scribbles like “the army above everything’ or “down with the revolution”, but nothing visually captivating.

Blatant pro-army or pro-government art belongs to Mubarak’s time, where the only art you’d see on the walls was election posters, or advertisements, or praise for Mubarak and the army. All those beautiful murals of the military’s conquests and Mubarak staring into the distance, with the people and the fellaheen dwarfed in the background. I’ve seen that for so long now, for so many years. So you just become saturated; you don’t even see it any more. Then, when you see the same art in communist countries like China and Cuba, you note the similarities. All dictators with their Ray-Bans and their little hats, looking very chic and never aging.

Are you in contact with many artists now, who don’t mind you sharing their work?

Yes. If I get to follow them around and write about them, I can document what they do. If I’m not with them when they make the art work, they can send me a picture so I put it online. Because when you make something and work on it for hours, and then the next morning it’s gone, that’s sad.

“When you see the same art in communist countries like China and Cuba, you note the similarities. All dictators with their Ray-Bans and their little hats, looking very chic and never aging.”

And they know I won’t give out their names or numbers. Then it depends upon what goals they have. There are those who have no problem with being photographed or being interviewed, and then there are a lot of graffiti artists who don’t want to get in touch and don’t want to be on my blog.

You wrote about how graffiti triggers reactions in the post about Adham Bakry being contacted by the advertising agency Zenith for making graffiti of La Vache Qui Rit (whose resemblance to Mubarak made it a popular mock of the former leader).

Yes. Adham was so happy when he called to say that they had contacted him. He was laughing like crazy. For an ad agency to track down the artists and then call him to say “please don’t make fun of me” is hilarious. Of all the things you should not say to an artist, “Don’t make graffiti!” is definitely one, because the artist will just say “OK, then, art!”

This is all happening in Cairo. What about other cities across the country?

I only worked on documenting the graffiti in Cairo, but I know that there’s an underground scene in Alexandria. The city is considered by many to be sort of the core or origin of the Egyptian graffiti scene. There’s the film Microphone about the underground scene in Alexandria, which features Aya Tarek. She’s very hardcore and respected by her peers, because she’s just as good if not better than her male contemporaries at creating street art.

“Of all the things you should not say to an artist, ‘Don’t make graffiti!’ is definitely one, because the artist will just say ‘OK, then, art!'”

Cairo’s street art is a mix of influences from many places, like a fusion between local and global elements. But the most popular of all must be the stencils?

Yes, stencils are very popular right now, because they’re easy to make and quick to use. All you need to do is print out your design onto thick paper, cut it out and spray over it. Once you have the stencil on the wall, it literally takes two or three minutes to spray, unless you’re making a complicated or large piece. You’ll need one friend to help you hold the poster straight or watch the road in case someone comes to cause trouble. Murals are more complicated and take more time and more people involved. Posters also need at least two people to stick up and are expensive to print.

What about the regional graffiti scene? There’s a growing amount of collaboration between different artists, isn’t there? The stencil of Bashar Al-Assad with a Hitler moustache, for instance.

I think that there will be a lot of collaborative projects in the future. In the past year, I noted two projects, one between El Teneen in Cairo and a graffiti artist in Beirut to make a stencil of Bashar Al-Assad as Hitler. El Teneen sprayed it on the walls of Tahrir and the Beirut artist made it on a wall in Hamra. It was also made in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia and there were plans for it to be sent to an artist in Syria to make there. Then there was the collaboration between Ganzeer and Ali in Beirut, where the Egyptian and Lebanese artists worked on a graffiti stencil called I Love Corruption criticising the Lebanese army’s corruption. There’s definitely a sense of solidarity and cooperation between graffiti artists from different countries. So we’ll have to see how far this can go.

4 thoughts on “Sharing the art”

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Folks please get a G+ share button on here :-)

We are working on it, it should be there soon :-)