Son of the sun

I.

It’s been three weeks since the explosion in Beirut and I still have no words.

“Are you in pain?” people ask me. I wonder about what they mean. I wonder about what to say.

I think of the deep injury in my left foot, the twelve stitches in my right arm, the tightness in my lower back. I try to find words to describe how it feels to have your flesh and bone invaded by broken glass and toxic nitrate. I think about hidden pains I have not yet located in my body because it is still so soon and I am still so numb. I think of Beirut and what was done to her. I think of trauma and what it does to us. I think of recurring nightmares at night. I think of complete strangers I see at the doctor’s clinic or on the way there, and of what I see in their eyes. I think of injustice. I think of our revolution. I think of disappointment. I also think of beauty; the beauty of pain and how it sometimes brings out the best in each one of us.

“Are you in pain?” people ask me. I wonder about what they mean. I wonder about what to say.

I think of all that. And then, I fumble for words.

Are you in pain?

No feels a little dishonest. But yes is a doorway into the unknown. Yes can go places I do not necessarily want to take the askers of the question with me to. So, I say sometimes. I say a little bit. I talk about how pain comes and goes. I talk about painkillers. I talk about not being able to feel a lot. I use but a lot, mostly to explain that it gets better or that it could have been worse, to keep the conversation light, to conveniently talk my way out of the question.

Are you in pain?

Close your eyes. How do you feel? What do you see? What would you say?

Are you in pain?

Yes, I am. Yes, thank you. Yes, I appreciate your concern. Yes, I really truly do.

But, for now, let’s leave it here, because I still have no words.

II.

It’s been 46 days since the explosion in Beirut and I am leaving the doctor’s clinic without a cast. It would take me another 40 days to get rid of the crutches, but today this is not an important detail. Today, my wound has finally healed and the sun is shining and I am feeling a great relief.

In the next days, as I begin to feel more and more safe about leaving the house and being back in the world, I begin to realise that my crutches gave complete strangers the license to ask me another big question.

My wound has finally healed and the sun is shining and I am feeling a great relief.

Shou sar ma’ak? They ask. What happened?

El-infijar, I say. The explosion.

Ouf… they say, with an astonished look on their faces that leaves the air thick with many more questions. Of course, the little more adventurous go for it: Bass, shou sar? What exactly happened?

And so, I begin to retell the story one more time. There are different versions of the story and the choice of which to recount depends largely on planetary alignments in both the sky and in my head. But the full version tends to begin with this line:

I am alone at home standing in the middle of the living room scrolling through my phone waiting for a real estate agent to come with a client for a viewing at 6.00 pm, because my apartment has been put on sale.

It’s 6.07 pm and they are still not here. And then, out of absolute nothingness comes a very, very loud sound from somewhere outside, and a deep silence falls over the city for what feels like a fraction of a second.

In this fraction of time, all of this happens almost all at once: I look out of the window and my mind takes me to 2005, when a wave of exploding car bombs hunted down politicians and journalists across the city, one at a time, for one whole unrelenting year. I think of Samir Kassir. I think of Gebran Tueini. I think of who it could possibly be now.

In this fraction of time, all of this happens almost all at once.

A wave of sadness washes over me, but before it has time to settle — BOOM — the second explosion goes off and makes a very, very violent sound. I feel an electromagnetic wave pierce through me. I see glass breaking in front of me. I hear screams from the street below. And then, I look down to the ground and realise that there’s a crater in my left foot and blood everywhere. My instincts impel me to leave the house immediately to the nearest hospital and I begin to find my exit: reaching for a towel to wrap it around my gaping wound, reaching for my wallet, the keys, the door, and then, reaching for the elevator and discovering that it’s not working.

The rest of the story is a telling of how I made it to the hospital.

I tell of how I descended five long flights of stairs on one leg, with my right arm holding on to the rail of the staircase and the other arm holding on to the towel around my left foot. I tell of how I began to lose my vision and my voice by the time I began reaching the ground floor. I tell of how I prayed for a miracle and how indeed many were sent my way: Fatima, my pregnant neighbour, the first to see me, who was at the entrance of the building and whose screams at the sight of me alerted people on the street to me; Abou Bilal, her father, who, out of nowhere, emerged with a big piece of white cloth; many, many men, who I faintly saw in the back of my eyes rushing from the street towards me, lifting me up, up in the air where I felt complete weightlessness, and carrying me into the backseat of a tiny red car; Ahmad, Fatima’s husband, the owner of the car, who started the engine and drove us to the hospital of the American University of Beirut, a couple of minutes down the road. In the car, Fatima in the backseat holding my foot and pressing on it with the white fabric as tears rolled down her cheek; Abou Bilal in the front seat cursing at everything and nothing; Ahmad driving atop broken glass against traffic at full speed; and me laying low on my back and witnessing horror on their faces.

I tell of how I prayed for a miracle and how indeed many were sent my way

Then, I tell of making it to the hospital, where doors were flung open and doctors were running everywhere. I tell of how my bloodied clothes were ripped off of me, how I was stitched and bandaged, while Fatima stayed next to me and chaos reigned all around us. I tell of much later in the night when doctors discovered that my foot was still bleeding and of how I was rushed to the operating room and operated on by three doctors for a good fifteen minutes without any anesthetic. At this point in the story, I have to explain that there was no time for anesthetics; there was only time to save lives — mine and the many others who laid on beds next to me.

Then comes the final part in the story, in which I share highlights from the time I spent at the hospital and try to explain how I left one week later feeling like I had just been rebirthed.

In all my tellings of the story, I find it easier to recount the facts than to describe the feels. There is also the question of how much to tell. Yet there is always the conviction that the story must be told. Because this story is also many other stories. Because words are also weapons. Because the act of telling is also a political act. Because in between the lines of our story there is also healing.

III.

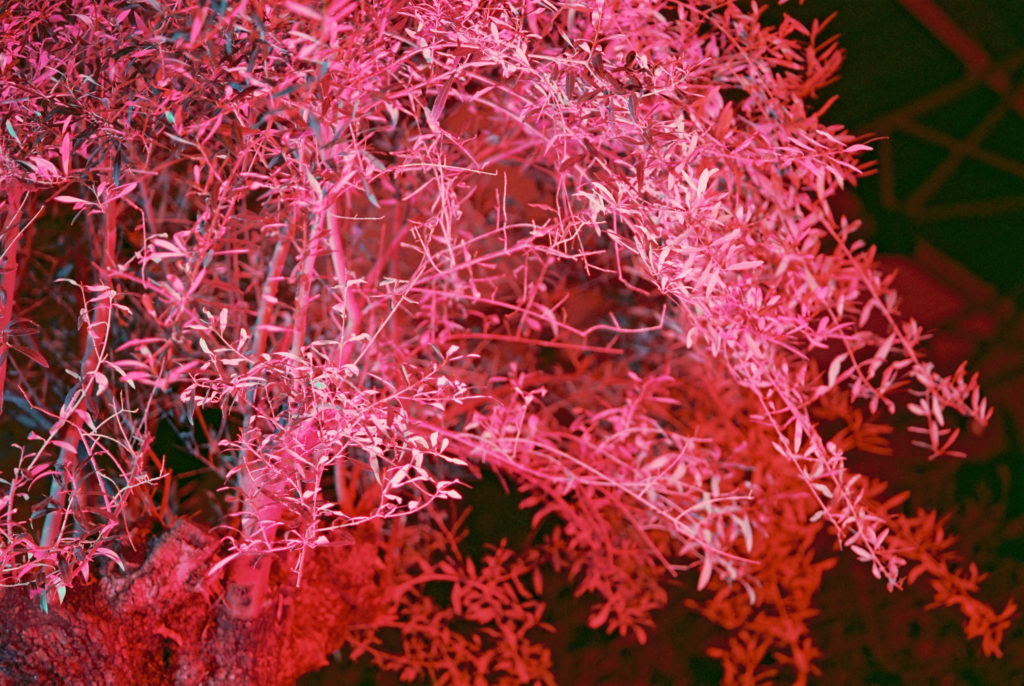

I have spent the past three months in the north, away from Beirut, recovering in my hometown with my family. During this time, I would look out of the window from my bed into the garden and the vastness that stretches beyond it and witness, day after day, how seasons turned and nature changed.

I would look out of the window from my bed into the garden and the vastness that stretches beyond it and witness, day after day, how seasons turned and nature changed.

I come from a place where people inherit olive trees from their ancestors and where much of life revolves around honoring that inheritance. We tend to the land, we care for the trees, and we wait for the olives every year. But in the past seven years, the seasons have been dry. The leaves of the trees have been infected by a virus that caused them to fall prematurely on the ground. And because the leaves protect the fruit, the virus basically spelled death to the harvest. Some say that it is caused by the dust from nearby cement factories, which lands on the leaves and prevents them from breathing. But this theory has not been without anomalies. This year, though, the olives held their ground and they were bountiful.

As the brightness of August softened into a lightness in September, there was anticipation in the air. Then came October and the first showers, which everyone was waiting for. Rain is said to bless the crop, and people wait for it before they start to pick. The first rain came on the day I completed my physiotherapy sessions and replaced the crutches with a wooden stick, which had been passed on to my dad by his eldest cousin. In the next days, as the sun shone and the land dried and I began to find my ground again, preparations started for the olive season. I was also ready for the picking: I had my stick and a newfound appreciation for this inheritance, which one day will be passed on to me.

I find it a paradox that an explosion that made me lose touch with my ground eventually led me to realise how much I am connected to my land.

I find it a paradox that an explosion that made me lose touch with my ground eventually led me to realise how much I am connected to my land. And when people ask me if I want to stay or leave, I find myself faced with another paradox. I have always hated how binary this question is and how it rarely if ever holds space for a middle ground. But I don’t know if I am going to stay or leave! What I know is that I am rooted in this land and forever connected to the story of its past. The journey to get back on my feet has taught me to accept the complexity of this past, but not to be burdened by it. I am actually made all the richer because of it. And my story is incomplete without it.

Healing is a process of coming back into wholeness. Throughout this process, words have a transformative power. What I think and what I speak matter. How I articulate my experience of pain plays a role in this process. Pain comes and goes, but it always has something to say. To sit with it is to learn to listen to it, and then to respond. Which is why, in many ways, healing is also a creative process. And like all acts of creation, it is transformative.

Maybe it’s not so coincidental that the trees bloomed again after seven years.

In the past three months, I have often found myself going back to what a friend of mine once told me after suffering from a wrist injury. “Bones are a metaphor for the heart,” she said; they break open so that the light could come through. Yes, light transforms, and photosynthesis is a prime example. Sure, I have been a victim of unimaginable violence. But claiming my story without placing myself as the victim in it is part of the healing process. It is how the light gradually comes through. It is how a breakdown becomes a breakthrough.

Maybe it’s not so coincidental that the trees bloomed again after seven years. I have always been intrigued by the many mysteries that lie within this odd number. There are seven colors in a rainbow, seven days in a week, seven chakras in the human body, seven notes in music, seven wonders in the world… In Arabic poetry, the seventh verse completes a poem. Before seven, it is not there yet. But seven is a breakthrough.

In the past seven years, I have constantly marveled at how my dad never lost hope in the land. He kept going back to it, and he kept trying. Because deep inside of him he believed in the miracle of nature, and that life always bounces back somehow. Because, like a poem unfolding into the seventh verse, we eventually get to where we need to be, no matter how dark or dire it gets. Because in the depth of us there is an innate attraction to the sun.

Inner migration was produced as part of the 2020-2021 Switch Perspective project, supported by GIZ. All illustrations by Aude Nasr.