On temporality and the Gulf city

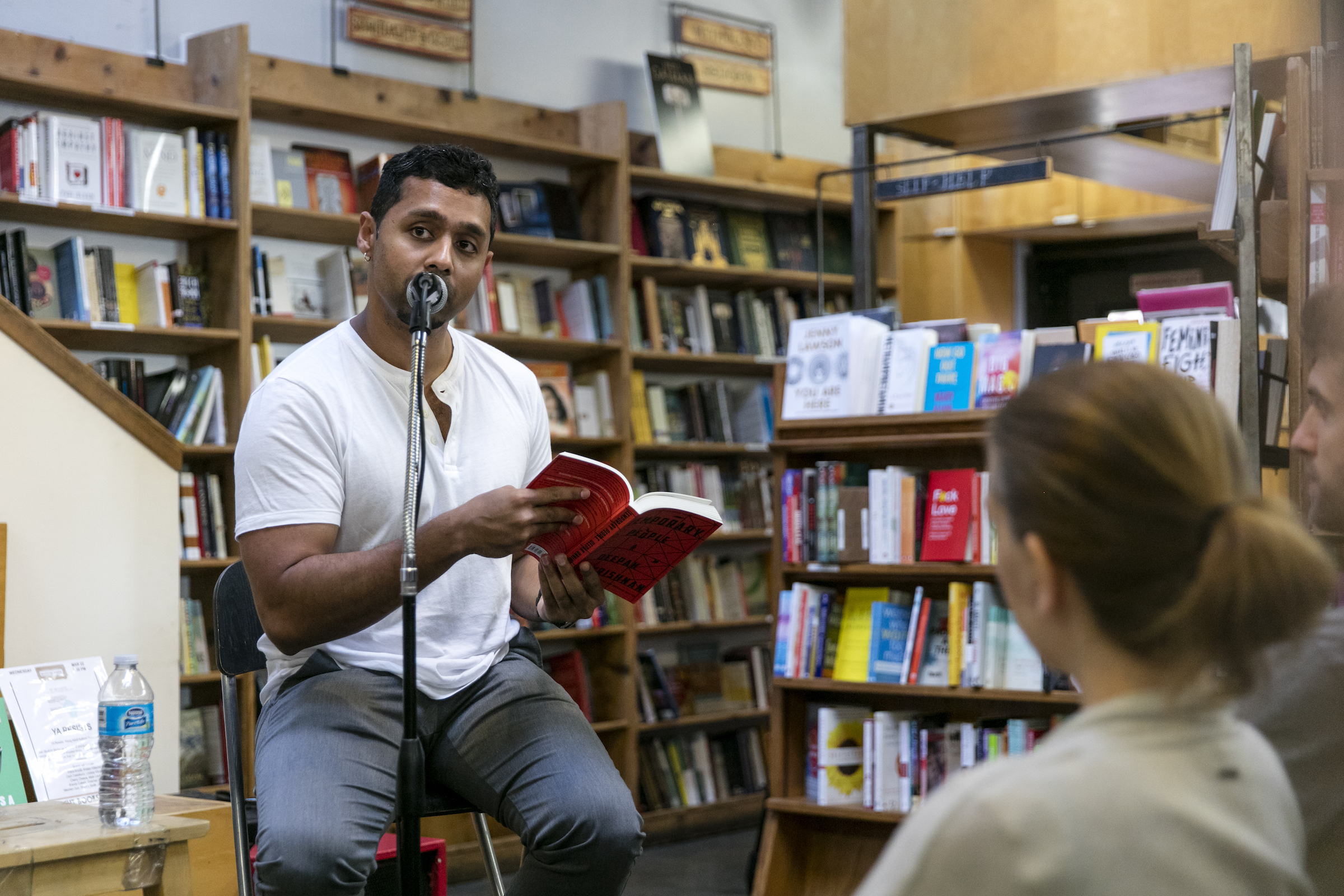

Talking to Deepak Unnikrishnan

We are dedicating two weeks to storytelling in the United Arab Emirates, with featured interviews with writers and storytellers/sharers and an overview of interesting events and people telling stories about Dubai, Abu Dhabi, the region and the world. First out, this conversation with author Deepak Unnikrishnan.

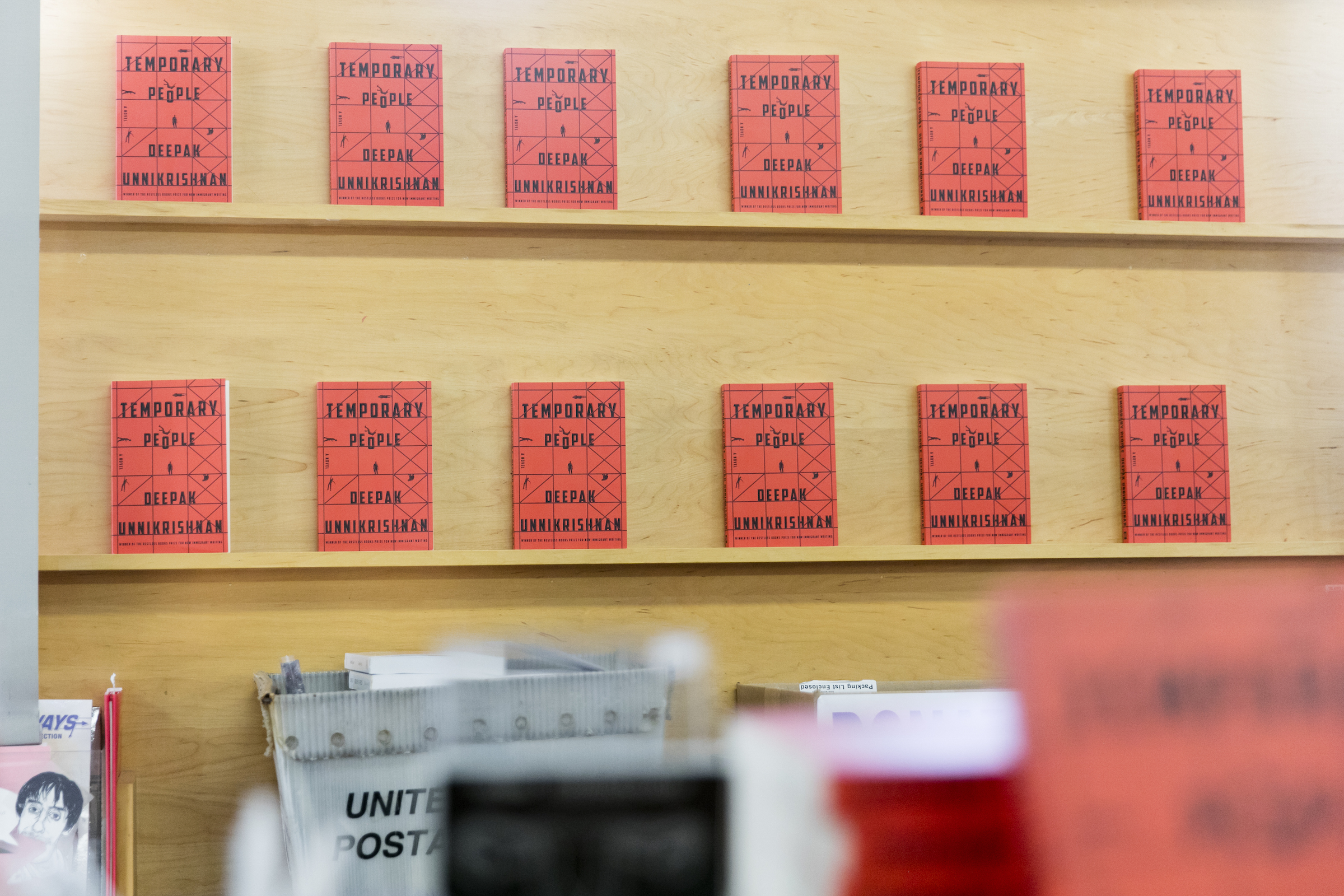

On the first few pages of the novel Temporary People, published in early 2017, is a black-and-white drawing of a construction crane, made from human bodies and resting on a pile of suitcases. The opening paragraph starts: “In a labor camp, somewhere in the Persian Gulf, a laborer swallowed his passport and turned into a passport”. In the following chapters, a display of characters are introduced: a woman gluing together pieces of labourers who have fallen to the ground on construction sites; a man, his father dying in hospital, trying to return to the UAE without a visa; teenagers and clowns and taxi drivers, and people, grown like plants in a desert greenhouse, in order to become labourers.

The underlying themes of these playful and absurd stories are familiar to anyone at home in the Gulf. Travel and migration, toil and labour, morphed identities and things built on temporary foundations are reality for many in the region, including the book’s author, Deepak Unnikrishnan. Raised since he was one month old in Abu Dhabi, to parents from Kerala, he lived for 14 years in the United States, to where he keeps returning.

In the book – his debut – Unnikrishnan plays with form and language, scattering words and phrases from Arabic and Malayalam, the language spoken in Kerala, throughout the stories written in English. He recently returned – for the time being – to the UAE, to write and to teach at New York University Abu Dhabi.

Mashallah News met Unnikrishnan at campus one afternoon to talk about his relationship with Abu Dhabi, how it features in his writing, and how he teaches storytelling to his students.

“I try to get my students as involved in the city as much as I can. I teach a course on street food for example, where I use food as a device to get them to go to places. One assignment I give them is ‘find me a Ugandan restaurant in the city’. This means that they have to start interacting with people – because there is no Ugandan restaurant in Abu Dhabi, only places where you can order food that is Ugandan-like. They will only know this if they ask taxi drivers.”

Here in the Gulf, where are the Gulf narratives?

That’s interesting. The cities of the UAE certainly have a rich culinary heritage. You can find some of the very best food from the subcontinent here, for instance. Apart from that, as a writer, what does Abu Dhabi mean to you?

“I was born and grew up about 15 minutes from here [campus] by car. This city raised me in a way. So there are things here that I understand innately and things I understand from the point of view of a child of parents that came – and stayed, and who will one day leave. I tell my students stories about the city that are based on how I remember it from the 80s and 90s, especially the old city centre. I came back to Abu Dhabi now because my family is here, and also because my work is related to Abu Dhabi. But I am not sure for how long I will stay. Because of how the country operates, I cannot be here forever.”

You are talking about the fact that you cannot get a citizenship, that your existence as a non-Emirati is always uncertain in that sense. That belonging can never be taken for granted.

“Yes. Whenever someone asks me what I identify as and wants me to pick a nationality, I refuse. I only give them the city, saying I’m from Abu Dhabi. And up until the point when I left to go to the U.S., I thought I was just at home. I was not in a position where I felt that I had left home. My parents, when they left Kerala, had left home, but not me. Today, I also consider myself to be from Chicago and New York City, where I lived for a long time.”

This notion of belonging makes me think about this comic, with a man walking down the street with bags in both his hands. When someone asks him ‘Where do you come from?’, he just answers: ‘The supermarket’.

“Yes. There is something about the truth – your truth, not something that others expect you to state. Because we have basically no control over where we are raised. Today, it is like I have a trunk full of memories and I don’t know where to put it. I can’t put it in India because some people there are so sure about what Gulf memories are supposed to be, and I can’t put it here because there is no language for it. In the States, where everyone has hyphenated identities or clarification categories, I can’t put it either. So what I do is I travel with the memories. I talk about them and I address them in the work that I do.”

It is like I have a trunk full of memories and I don’t know where to put it … So what I do is I travel with the memories. I talk about them and address them in the work that I do.

Tell us about that? About your novel, Temporary People, which received many good reviews.

“People are reading it, that’s great. It was published by a mid-level press and because it won a prize with the word immigrant in it, and revealed to the public at a time when a hotel tycoon was elected to be the president of the United States, I’m assuming there was interest in reviewing it, besides the truth that my publishing house really went to bat for me. So I can’t really complain – because the book was pitched as literature coming from a place that not everyone knows. Then you also have people who grew up here, who are in my position, and they read it with a different set of notions in mind. In some cases they are looking for something related to their memories and want a conversation about it. For some, it might be identity; for others, a sense of home or what home is supposed to be. Something basic like ‘I recognise that street that you wrote about and I’ve never read about my street in literature before’.”

That is because you are putting words to a major shared experience, one that had not really been portrayed in literature before. And that makes you think: ‘How come no one wrote about this before?’

“You are right. But I think the writing has been available, it’s just that publishers have not been willing to put it out. There has just not been a receptive audience or receptive publishers [to the idea of literature from Gulf diaspora/immigrants]. And people were also not sure about how to address the issue of identity, what it means to be us. In many countries, you have a term for the immigrant who has just landed. Here, you don’t have that. The proposal is very blunt: ‘Come here for work and you may leave after that’. But when you call people a guest worker, or migrant worker or any kind of worker, is that enough?

The proposal is very blunt: ‘Come here for work and you may leave after that’.

This is probably what the book is attempting to rectify. That there is no vocabulary to fully express or understand what some people go through. And I’m not talking only about trauma. I’m talking about joy. About simple things in life like having tea by the roadside – how do you talk about that memory?

There is also a gap of information. Because every time you make a phone call and you’re calling home – perhaps not every time, I should not generalise, but at least in my family – both parties are at some point lying. ‘How are you? I’m OK, how are you?’ and then a bit of small talk. There is very little time to have a truthful conversation about pain or sadness or just yell at your kid. Because we want that transaction to be cordial. It was similar when our parents took us to Kerala when we were younger. We were treated like royalty: everyone wanted to make us happy. There were few moments of normalcy, when people just stopped performing.”

I’m not talking only about trauma. I’m talking about joy. About simple things in life like having tea by the roadside – how do you talk about that memory?

When things are written about work migration and the Gulf, the narrative is almost always one of victimhood. People are rarely something other than passive subjects. What are your thoughts on that?

“I think the word here is agency. I’m not saying there is no struggling and suffering, because there absolutely is. My parents are examples of that. We grew up poor. Not in a labour camp but we grew up without having things and lacking hope or ambition. And us who were born here, we understood that the city could be very blunt with you – in respect to race, language and so on. We had to figure out a way to not only understand that but to live in a way that acknowledged our presence. At the same time, my parents made choices on behalf of the family. I get that now. I’m not claiming that people are not unhappy with what they are doing here, especially if they work in construction. But I think it’s important to be careful and ethical when individuals are reporting on behalf of the other, or how they write about the other, especially when the writer is in a position of privilege, owing to his/her profession, race or nationality, or a combination of all three.

Us who were born here, we understood that the city could be very blunt with you – in respect to race, language and so on. We had to figure out a way to not only understand that but to live in a way that acknowledged our presence.

So when people ask me: ‘How does it feel to write about the voiceless?’ that unnerves me. That is so disrespectful, I’m not writing about the voiceless. I’m writing about one experience that I understand innately. As a writer, this is what I can do: dip into a certain kind of memory that slowly erodes, or is getting erased, simply because people leave. For me, that visibility is more important than a trauma narrative. What people dream about, what their kids’ names are, what they like to do on Sundays. Then they become real.”

You also have a personal experience of leaving and then returning. How did that shape the book?

“I wrote the book after having left Abu Dhabi. In fact I couldn’t have written it here because I didn’t know enough. It was only when I went to the States for the first time in my life that I understood what my parents went through. I left when I was 20, and my father had been 21 or 22 when he left to go to the UAE. So the departure hit me like a ton of bricks. Everything made sense at that point. I suddenly understood why my father had become what he became and my mother what she became.

As a writer, this is what I can do: dip into a certain kind of memory that slowly erodes, or is getting erased, simply because people leave.

It also made me think about narratives. How in the U.S. you have the Cuban American story, the Indian American story, the Native American story, which needs to be talked more about, if you ask me. Everyone has something to latch onto. But here in the Gulf, where are the Gulf narratives? I only found the usual: went there, lived there, sacrificed. I didn’t find anything that I could relate to.”

So for you, writing this book, chances are that you will quickly be labelled a ‘migrant writer’. How do you feel about that?

“I think there are certain things that I’ve learned I cannot escape from. I’ve just resigned myself to the fact that I won’t be able to escape. But if you read the book, and this is what I keep telling people, it’s not about being an immigrant: it’s just a writer writing.”

Yes. North American writers for instance don’t get that label, even though the U.S. essentially is an immigrant country.

“Exactly. When you read Philip Roth you don’t think of him as an immigrant. You don’t say ‘Here’s another white writer writing the immigrant story about Jewish families going all the way to Jersey to make a life’. And if you read Isaac Singer, who is a quite astounding short story writer, you don’t read him and go, ‘He writes about immigrants’. You just don’t do that. Singer, man, he archived his people and their language Yiddish in his tales. That’s the sort of thing I’m hoping to do too.”

Perhaps there is more urgency here because of the transient nature of the place – because we are not sure how long we will be present.

Still, we do have a brain that tries very stubbornly to put things in boxes, to categorise and make sense of things that way. To help us navigate in the world, basically.

“Yes. So there was a review in the Los Angeles Review of Books where the gentleman compared [Temporary People] to a book called Cane by Jean Toomer, who is a black writer and was using language back in the day to express what could not be expressed, as far as he was concerned, with what the black experience was supposed to be. For me that was an astonishing comparison, because most reviewers veer towards what’s familiar: South Asian writers or brown books. And he compared me not to them but to a black writer – because he was looking at content. So you do have people who think differently and offer a little bit more perspective. And then, I do also understand that there is very little, in this point in time, that has been published about people like me from the Gulf.”

Finally, what literature or art do you think will come out of Abu Dhabi and Dubai in the future, in the context of this experience?

“There is something out already: The Promised Land, a book of poems by André Naffis-Sahely who grew up in Abu Dhabi as well. Then there’s a book set in Saudi Arabia, a young adult novel by Tanaz Bhathena who was born in India and grew up in Saudi. I’d also pay a lot of attention to visual artists. There’s Reem Falaknaz, a photographer who documents Emirati life that is not seen so much: she goes to the mountains, the villages. And there’s Lantian Xie, a visual artist based out of Dubai, who was part of the Venice Biennial last year. For that biennial, out of the five artists that the UAE chose to represent the country, I think three were non-Emirati. And that’s a big statement. And if I could add another name to this list it’s Raja’a Khalid. Her works make me pause.

I think a period will follow when people do what they did in many other countries: document a certain experience; excavating, almost archiving, it. Because certain things need to be said. In my case, I feel a sense of responsibility to document my parents’ generation. And perhaps there is more urgency here because of the transient nature of the place – because we are not sure how long we will be present.”