The Samaritan village

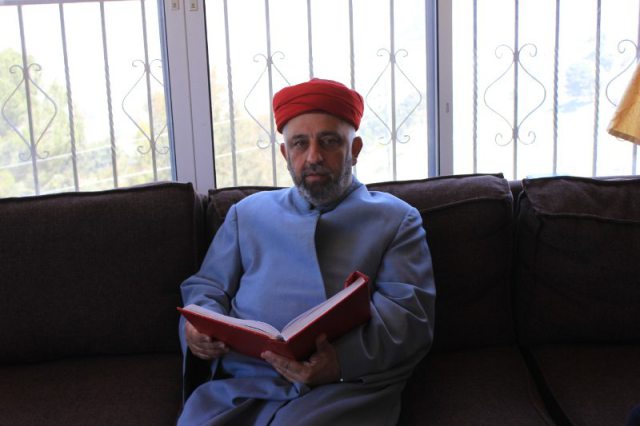

Khader Adel Cohen is a well-respected and popular leader. When I enter the Samaritan village of Kiryat Luza atop Mount Gerizim, in the outskirts of Nablus, the priest of the local synagogue awaits me, accompanied by two of his sons and a couple of villagers.

A Samaritan village in 2014? When you imagine such a community, your memory travels back through the pages of the Bible, remembering the parable of the Good Samaritan (Luke 10) or the Samaritan woman in Nablus who draws water from a well and gives it to Jesus (John 4). However, the Samaritan people played a key role not only in ancient Palestinian history, but also in today’s culture, religion and legacy.

“We used to be millions, currently we are roughly 700,” explains the priest with a vague smile. The Samaritans were a significant nation but they were decimated across the centuries by forced conversions to Christianity and then Islam. Today, Samaritans live in two surviving communities: Nablus, and Holon in Israel.

Samaritans consider themselves the authentic Israelites. They believe in one God and one prophet, Moses. Regarding the sacred texts, they only recognise the authority of the Hexateuch (the Torah and the Book of Joshua).

“Due to our history and tradition, we feel very connected to Nablus and the region. Our children go to school and university here. We work in the town, often in the city centre,” explains Cohen. Until 1948, the community lived in a neighbourhood called Yasmina in the old town. In the mid-50s, they moved to Hay as Samara, near an-Najah University.

Then, as of the first intifada in 1987, and more so in 1995, Samaritans gathered at the top of Mount Gerizim, their holy mountain. “We owned some land there, and used to meet for a month each year for our religious festivities. Before moving into our concrete houses, we slept under the tents.”

Since the beginning of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, they are in the middle of an identity dilemma: “Israelis consider us Palestinians as we speak Arabic and live in Nablus. Palestinians think we are Jewish as we follow the Torah and use Samaritan Hebrew as our religious language.” Quite surprisingly, they use both Palestinian and Israeli ID cards.

“We receive money from both governments,” explains Cohen. Leaders from all sides seek their support for an obvious reason: their longtime geographical and historical legitimacy in the region. In addition, Jordan is a precious ally of the Samaritans. In 1948, King Abdallah vowed his unconditional support to them.

“Palestinians think we are Jewish as we follow the Torah and use Samaritan Hebrew as our religious language.”

“We feel closer to Palestinians than Israelis,” claims the priest: “Our life is here, in Nablus. It is normal that we feel closer to them. They are our children’s friends, their parents, our colleagues.” Samaritans have shown their deep attachment to Nablus throughout history. Under Ottoman domination, thousands of them chose to convert to Islam rather than be exiled.

Ibrahim Sadaqa was the first non-Samaritan to convert to Samaritanism in 1921. At that time, it was a matter of survival. “Conversions used to be forbidden, even during the darkest times of our history.” Figures are striking: in 1917, at the fall of Ottoman Empire, only 121 Samaritans remained. This tiny community torn by history seemed to be condemned to disappear. However, in 1970, the number of Samaritans rose to 317 and today 785 people self-identify as Samaritan.

Given the close links uniting Samaritan families and the prevalence of endogamy, each new birth is at risk of congenital malformation. In the middle of the 20th century, nearly 7 percent of Samaritans were affected. A few years ago, lacking any alternative, the community leaders agreed to let men marry foreign women, under the condition they convert. During the past five years, eleven Ukrainian women have joined the community. A few Muslim spouses have come from Turkey. Heirs of a multi-millenial faith, Samaritan disciples are using modern strategies to make their community survive: online dating, distant choice for spouses and genetic testing are part of daily life.

Cohen opposes such practices: “I don’t want my sons to marry foreigners. At worst, it is better to take converted Jewish women,” he explains directly. He claims that this decision has weakened the community and fuelled more dissensions.

With the demographic issues partly solved, the Samaritan community was compelled to find new solutions to sustain itself economically. Thanks to their binational status, many Samaritan entrepreneurs are proposing unique delivery services to local businessmen.

Those who export goods to Israeli cities must cross Israeli checkpoints, sometimes delaying deliveries in a very harmful way. “Samaritan drivers are helpful as they are able to deliver goods to Israel in a one day time span,” explains Asem, one of Cohen’s sons.

After nearly disappearing at the beginning of the last century, the Samaritan community can envision its future with a certain optimism. Following the reformation of the tight social codes that governed the community for three millennia, their religious particularities have been preserved.

All pictures by Josselin Brémaud. Text edited by Stephanie Watt and Ellie Swingewood.