The tattoo artist of Muqattam

Marking a Coptic tradition

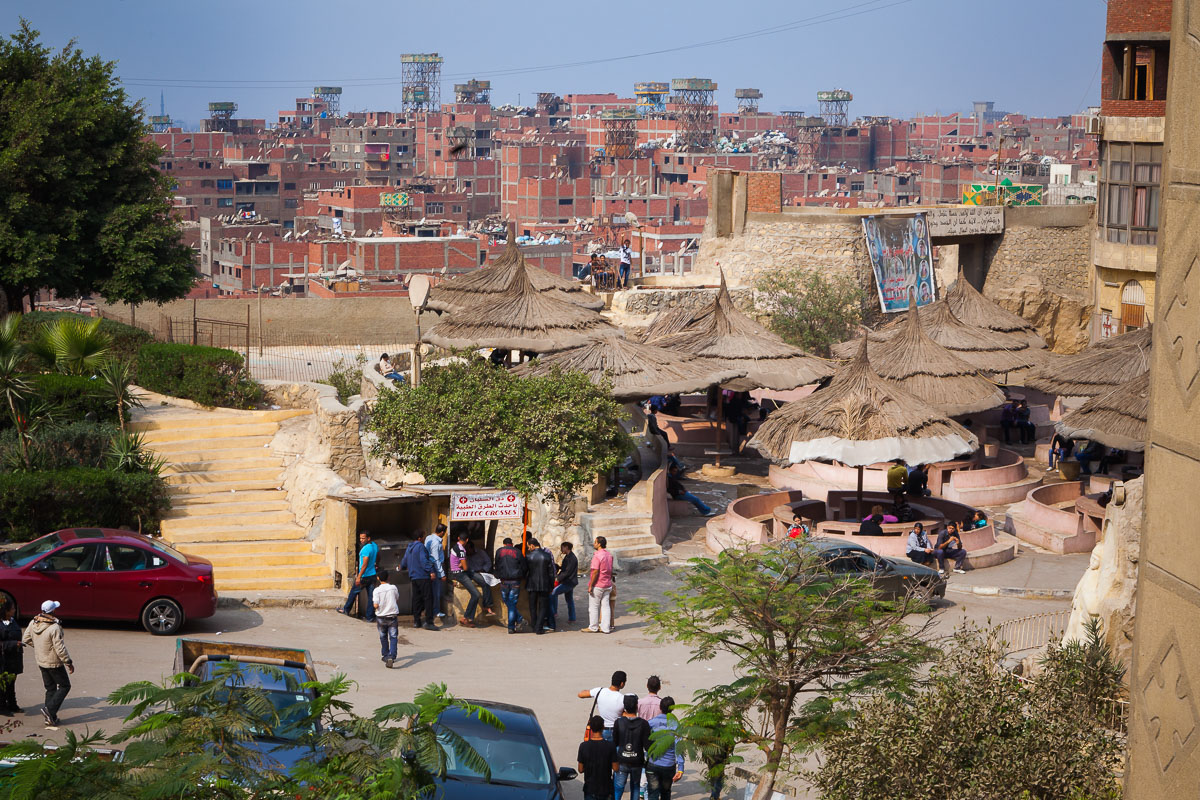

Every afternoon, after finishing his engineering job in the city, Girgis Gabriel Girgis makes his way up the slopes of Muqattam, a large, dusty hill in south-eastern Cairo. He drives through Manshiyet Naser, the area where residents recycle by hand much of Cairo’s daily household waste, to reach the monastery of Saint Samaan. This is where, in a booth right outside the largest church in the Middle East, Girgis works his second, and much beloved, job − as a tattoo artist.

Girgis’ place is small: a booth with two chairs − one for himself and one for the customer − a table with bottles of ink in many colours, and a few shelves on the sidewall where wooden stamps are lined up. Yellow and red letters read “دق”, the Arabic word for tattoo, and there are a few stickers from Tattoo Magazine.

The booth is busy, especially today on the first day of Eid el-Adha, one of Egypt’s main holidays.

“It’s more crowded than usual because of Eid. When it’s the weekend or when the schools are closed, lots of people come here. So I’m busy today,” says Girgis. “On a normal day, it’s quieter. But I still have customers daily. I usually do around five to seven tattoos a day. Almost all of them with the same motif: a Coptic cross.”

“I usually do around five to seven tattoos a day. Almost all of them with the same motif: a Coptic cross.”

The small crosses are worn by many of Egypt’s Copts. Dark blue, no more than a centimetre square, they are tattooed on the inside of the right wrist or on the back of the hand. Throughout history, the tattoo has functioned as a form of social identification for Copts, marking religious and communal belonging.

The community, making up some 10% of Egypt’s population, or 8 million people, has a long tattooing tradition, inherited from their Pharaonic ancestors. It’s these ancient Egyptians that are among the very first to provide evidence of the art of tattooing: mummies with tattoos have been found from the second millennium B.C.

The ancient Egyptians are among the very first to provide evidence of the art of tattooing: mummies with tattoos have been found from the second millennium B.C.

Egyptian Copts, just like those from Ethiopia, would traditionally get their tattoos on pilgrimage to Jerusalem. For pilgrims, the cross tattoo marked a proof of their journey and was a symbol in which they took pride. Jerusalem tattooists used wooden stamps in order to speed up the process, making it possible to tattoo large numbers of pilgrims. The same sort of wooden blocks are still used by Egypt’s Coptic artists today. Girgis points to his collection of stamps, which has motifs ranging from the Virgin Mary and Mar Girgis to crosses of various shapes.

Egyptian Copts, just like those from Ethiopia, would traditionally get their tattoos on pilgrimage to Jerusalem.

“These are among the tattoos I do. Mostly religious motifs: the portrait of Jesus, crosses, saints or churches. But I also make freehand tattoos, anything people want me to do. It happens that I do non-Christian tattoos as well, but that’s mostly on foreigners, not Egyptians. The Egyptians come for religious symbols.”

Tattoos are an important cultural expression for many Copts. While the old female custom of wearing a cross between the eyebrows has now disappeared (but is still practiced among Ethiopia’s Christians), the small cross on the wrist is common within the community.

For most Coptic children, it is natural to get a tattoo by Girgis or one of his colleagues, usually outside the church during a national moulid. There is even a popular Coptic children’s song that starts with the line “Do you want to know why I’m Christian … And why I wear the cross tattoo on my hand?”

“The machine I use now is my own invention. The old one wasn’t very good, and it made lots of noise. So I constructed this.”

Girgis’ booth is surrounded by people talking, waiting for a tattoo, or watching others getting inked. Families, couples, friends and neighbourhood children make up the crowd around the tiny outdoors studio. Many have had their wrists tattooed by Girgis; some wear his art on their arms and shoulders. A young man shows a big cross tattooed on his back; a girl in her early teens rolls up her sleeve to display three tattoos on her right arm.

“I’ve always loved to draw, that’s how it all started. Then I learned tattooing from a relative,” explains Girgis. “Doing it properly is very important. I use a new needle each time. Same with the ink.” He shows the bin in the corner, full with disposable needles and small capsules of bluish ink. He picks up his tattoo machine. “I’ve improved my tools as well. The machine I use now is my own invention. The old one wasn’t very good, and it made lots of noise. So I constructed this.”

“Now, people come here asking me to fill in their tattoos, or to make new ones. They’re not scared or trying to hide that they’re Copts. They’re proud about their identity.”

Girgis looks up while preparing to tattoo the wrist of a boy, who is accompanied by his father. “There’s been a change recently, since the ahdath, the events,” he says, referring to the killings of 27 demonstrators during the mainly-Coptic protest on 9 October, known as the Maspero Massacre, and the extremist attacks on churches that preceded it.

“Now, people come here asking me to fill in their tattoos, or to make new ones. They’re not scared or trying to hide that they’re Copts. They’re proud about their identity. So they want to show that through their tattoos.” The father next to Girgis nods his head. “Yes. It’s about dignity.”

Whatever reason for doing the cross tattoo − communal, religious, personal or other − Girgis will make it in less than 10 seconds; so short that some kids even manage to hold back their tears before jumping down from the chair with a victorious smile. The price for one? Ten gineihs, a bit more than €1. “But the price is not fixed,” says Girgis. “I don’t ask everyone for 10 gineihs. Those who can pay, yes, but others, I’ll ask them for five. Or even nothing, from those who can’t afford. Mish assasi el flous − The money is not essential.”

3 thoughts on “The tattoo artist of Muqattam”

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Nice to know the man behind one of my pictures:

http://philippbreu.com/portfolio/cairos-zabbaleen.html

Girgis

I love your work, well done & God bless you.

me too love to draw but not good as you are, I live in Australia now with my entire family.

I am scientist & mother as well’ and as you know egyption ladies not really allowed to work as tattoos artist, even when I live in a country full of freedom still our traditions still part of our blood.

I am awear of how busy you are, but I couldn’t help myself from writing to an Coptic brother like me.

Please, if you have any time you can write to in Arabic language, which I miss a lot.

By the way I am away from my beloved Egypt for 22 years now.

At last, thank you

Your sister that share the love of Jesus Christ with you.

Hayam Ghali

Stand tall and be proud of your heritage and faith in Jesus Christ. Hail to the King! We Christian American admire you and pray for you. God bless you!!