The word ‘revolution’

Back on everyone's tongue

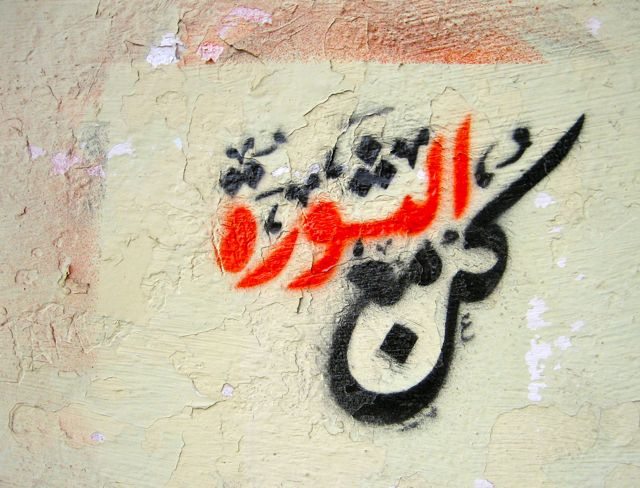

Together with the now iconic الشعب يريد اسقاط النظام, “The people want the regime to fall”, there is another chant that will write the pride and courage of Egypt into the history books: كن مع الثورة “Support/be with the revolution”. Tagged on walls and printed on posters both in and outside Egypt (even decorating jewelry from a Beiruti designer), the phrase was coined by visual artist Mohamed Gaber.

“كن معالثورة became an icon: I saw people with the image every time there was a protest.”

Well known from both the streets and online community of Cairo, Mohamed, called Guebara or Gaber by friends and those following his tweets and blog, is one of those who made the revolution a reality. Mashallah met with him to speak about his passions, his art and his commitments, and how all these came together during the revolutionary moment.

Your creative work and artistic engagement, how did it start?

A visual artist polluted with politics from Cairo, I’ve practiced art for a long time, although I never studied it academically. For me, it all started with making drawings on walls of my neighborhood. First, I didn’t even use spray cans, but the cheap paint and brushes that I could afford at that time. While the stuff I did sometimes was good, other times it was leaking and ugly. But, it always felt good because it was a way of expressing myself.

“Events like these are the result of a long process, and visual artists from Egypt and the Arab world have played a great role in this.”

A turning point was 2006 when I came across the book Graphic Agitation. The book proves that art and graphics can deliver a message very effectively, and even change people’s minds and lives. Today, I run a blog where I write about politics and publish artworks from my graphics and street art project GAS. And, I tweet the revolution.

Everything happening across the region now, especially in your home country Egypt, what role do graphics and art play in this?

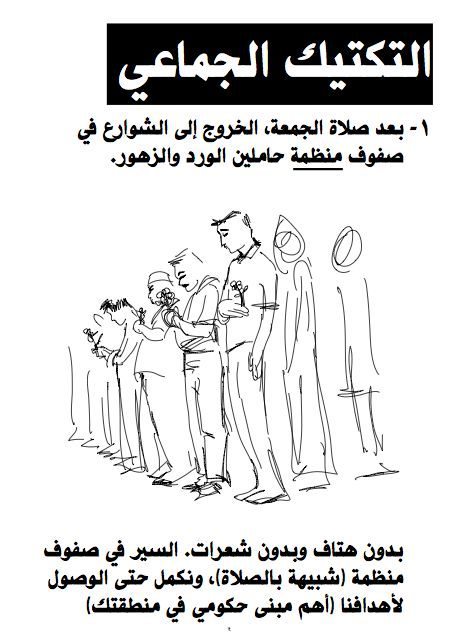

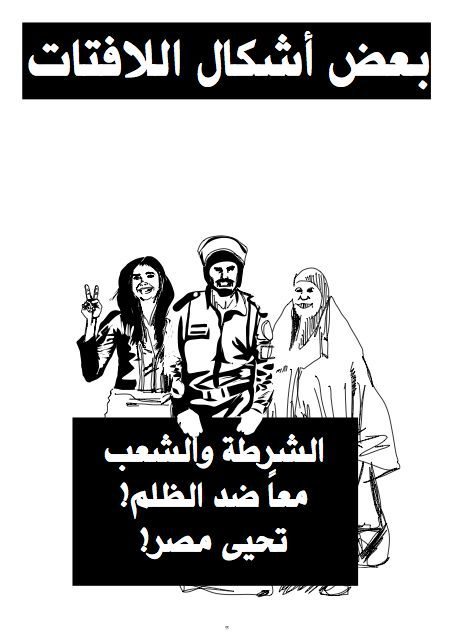

Graphics and art have played a great role in agitating; not only during these weeks, but throughout the last couple of years. Events like these are not something that happens overnight. They are the result of a long process, and visual artists from Egypt and the Arab world have played a great role in this. I’ll give you an example: a graphical handout that was circulating the streets of Cairo. It’s a revolutionary manual, describing things like how to move around and what to do when attacked by tear gas. And I know for sure that the manual had an impact: I saw people on the streets doing exactly as described in it. Exactly!

On that same topic of art that impacted the protests, the كن معالثورة piece was made together with Brazilian illustrator Carlos Latuff. How?

The cartoon is Latuff’s and the calligraphy is mine. The piece was actually made already in 2008, for that year’s general strike, and has been used during many demonstrations since. It became an icon: I saw people with the image every time there was a protest. Students and labour used it, even Islamists did. And the Muslim Brotherhood were spreading it online! So, the concept of revolution had actually been around for a long time before 2011.

“Making artwork against Mubarak was a way of telling Egyptians that he is not a god.”

As for the كن معالثورة slogan, it was inspired by a phrase used a lot in Egypt: كن معالله, which means Be with God. I choose to do it this way because كن معالله is familiar to people. In Egypt, which is a religious society, replacing the word God with revolution was something big. It meant making revolution an attainable option. Making artwork like this, against Mubarak, was a way of telling Egyptians that he is not a god and you can chant against him.

What about the message كن مع الثورة? It tells people to take action, to do something.

Let me say something about the Egyptian street back in 2005-2006, when the new movement started to get a voice and speak up against the regime. At that time, when there were only government-run newspapers, the media had been brainwashing people so much that the word revolution was not even in their vocabulary. They regarded the dictator as a father, even a god. It came to a point when I decided I had to start working to break this god-image.

“In this country, everyone has been brainwashed at some point in their lives.”

So, I started the GAS project with the goal of bringing the word revolution back to people’s tongues. What I did made people think that: either I didn’t live in Egypt and therefore wasn’t scared, or I was crazy to not be afraid of getting detained or killed, and for even thinking that people might revolt. But then, this year, I met those same people in Tahrir. Now, they were joining the revolution!

What we did was hard: working against a system which has all the tools to brainwash people. The governmental TV – the only source of information to many Egyptians – kept saying that: no, there’s no revolution. Instead, they showed an image of the calm Nile, like they were waiting for the fish to come out or something! So, some people were thinking that: ok, there’s no revolution. In this country, everyone has been brainwashed at some point in their lives. Myself included. Once, when I was ten years old, my mother came back from work and found me in front of the TV with the telephone, trying to call the governmental channel to congratulate Mubarak on his birthday!

How did it feel realizing that you had been brainwashed?

When I started to understand that, it was a real chock. I discovered that I had been fooled all my life. Things I used to believe in weren’t true – even the history that they taught us in school was wrong. They made heroes out of thieves, and no one talked about the real heroes. And the newspapers, all they spoke about is how great Egypt is, how the investments are excellent and that life is getting better all the time, although we could see that it’s actually getting worse. But then, with the internet and the new media, things changed. Internet really was the boom that blew up all those lies. Without the internet, we would never have had the chance to do what we did.

“Without the internet, we would never have had the chance to do what we did.”

So, combining art and the internet is a good strategy for social and political protest?

Totally, yes. And the social networks played an awesome role in that. Now, we know what is happening every second. Twitter played a great role in the movement we had in Egypt. Before these recent events also: last year for instance, I was training workers on how to use Twitter on their phones for reporting strikes. Same thing with the last project I worked on: an infograph comparing the situation in Egypt to Tunisia before their revolution. I wanted to tell Egyptians that: see, it’s even worse here, we have to have a revolution! But then I never had the time to complete the project. They revolted without it!

Illustrations from the manual, which can be found complete with English translations here.

5 thoughts on “The word ‘revolution’”

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Man, that manual is terrific. Such an inspiration for people all over the world, what you did in Cairo. With you all the way. And please, all eyes on Egypt now so that the tyranny won’t return!

ye that is right the all social network make a greet role in this revolution but the main thing that blew up this, is the life and the situation that we are in it

and thexx