Turkey’s bird super-highway

Saving the wildlife in the east

It may mark the borders of four different countries, but the Aras River still feels like the middle of nowhere.

Rising near the eastern Turkish city of Erzurum, it runs through Iğdır province, then along the country’s border with Armenia, which has been closed since 1993. Further on, it divides Turkey and Iran from Naxçivan – an exclave of Azerbajian.

Where the Aras passes through Iğdır, boys stand on the fringes of marshes selling leeches to the odd passing motorist. The hills nearby are barren cones of earth, like spoil heaps of a vast mining enterprise.

But, when you look up, the skies are a super-highway. Each spring and autumn millions of birds stop off or nest in the region, making it a vital hub in a migration route spanning Africa, Europe, and Asia.

The Aras is also the site of one of Turkey’s few bird ringing stations. ecologists catch, ring, and release thousands of birds a year in the hope that one day the data they gather could help save this ecologically rich region from the threat of development.

With a booming population and a GDP that expanded 8.5% last year, the country is faced with the question of how to balance economic development with wildlife conservation.

The government’s answer has been to loosen environmental safeguards on a swath of formerly protected land to ease the way for a massive infrastructure program.

This includes a plan to harness Turkey’s entire hydroelectric potential by 2023, creating a total of 4,000 dams and power plants on the country’s rivers. Two years ago, the government changed an environmental law, meaning riparian marshes like those on the Aras are no longer considered wetlands, making them harder to protect.

In 2006, the wildlife charity KuzeyDoğa opened its bird ringing station on the Aras marshes near the village of Çığrıklı. Two years later, it began lobbying the government to grant protected status to the marshes. There are consistent rumours that a dam project is on the way that will flood the marshes and village.

The charity hopes the information it gathers will help strengthen the case for the wetlands’ protection. The marshes cover a tiny area of no more than 10 km², but support a huge diversity of bird life. Since opening the station, KuzeyDoğa has recorded 237 species here and ringed 162.

The volunteers working here may be the rarest breed of all. In Turkey, people are generally indifferent to the significant threats facing the country’s environment. In a survey carried out in 2010, only 1.3% of respondents viewed environmental issues as a serious concern. Meanwhile, only around 50 fulltime professionals are employed by the country’s conservation NGOs.

But, Turkey’s environment is in trouble. In February, Turkey was ranked 121st out of 134 countries for biodiversity and habitat preservation in an annual index compiled by Yale University in the United States.

Those working at the Aras ringing station are mainly biology students from Istanbul, Izmir, and Ankara, or from nearby Kafkas University in Kars. Others have been drawn from as far afield as Kenya.

Many have a sense of what the evolutionary biologist Edward O. Wilson called ‘biophilia’: the innate human fascination with other living entities and systems.

Ringing the birds is a way of seeing them up close, and at the same time gathering data that will help safeguard their survival.

A volunteer holds aloft a red-rumped swallow, Cecropis daurica, which is scarce in this region and has arrived at Aras after a migration that may have started in the savannas of Sub-Saharan Africa.

Turkey is among the most biodiverse non-tropical countries in the world. It hosts an estimated 10,000 plant species, 3,000 of which are endemic. Eastern provinces such as Iğdır are among the richest in wildlife.

Volunteer Yakup Şaşmaz removes a barn swallow, Hirundo rustica, from a mist net.

A bluethroat, Luscinia svecica, one of the more common birds caught at Aras.

A wryneck, Jynx torquilla, which is classified as near threatened in Turkey.

The Aras River, which runs through Iğdır province, hosts ecologically important marshlands that are currently unprotected.

A bird ringer examines a sparrowhawk, Accipter nisus, one of about 30 bird of prey species that occur in the region.

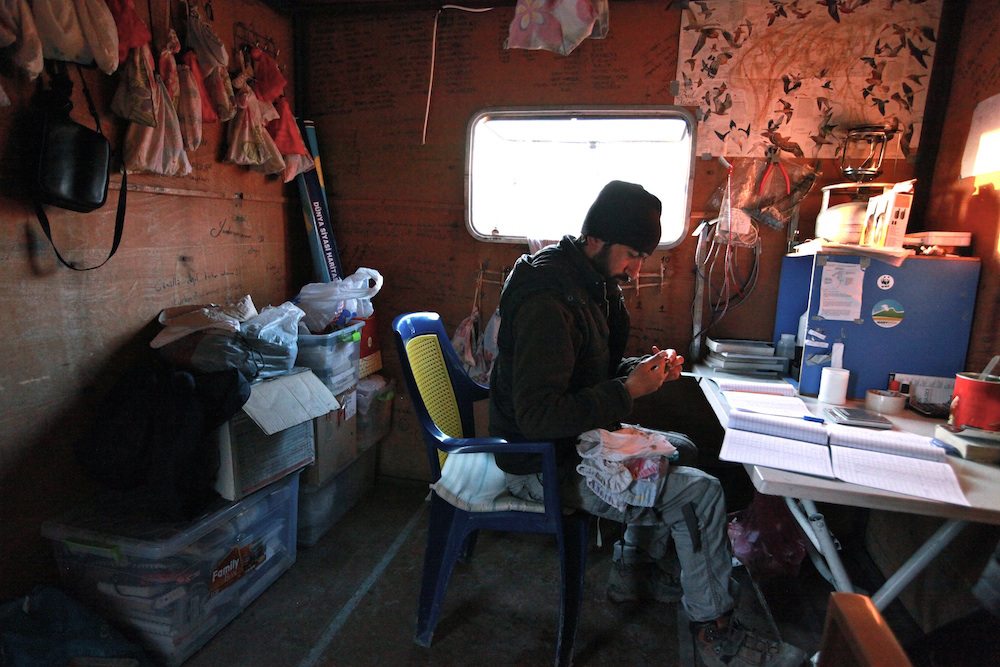

In the caravan where KuzeyDoğa carries out its work, a volunteer identifies a species of pipit. Those ringing the birds must have a licence acquired by training.

When darkness falls, volunteers work with head torches. Work starts at first light – around 5am. On days when many birds are caught, it can continue until midnight.

Sedat Inak, a PhD student at Kafkas University in Kars, is head of the ringing operation at Aras, spending six months of the year at the station. The bags on the walls behind him contain birds waiting to be ringed.

The piece was edited with the help of Ellie Swingewood and Angela Häkkilä.

5 thoughts on “Turkey’s bird super-highway”

Comments are closed.

Save our planet! Really, 121 out of 134? That is horrible. Shameful…..