Umm Ali’s building

Neighbours: A series of seven stories

Wherever we are in the world – home or away, in the place we were born or somewhere else – there will always be someone next door. A neighbour, a person living by our side. We may differ in manners and ideas of how things should be done, but we will remain closely connected – because borders and walls, bushes and fences from metal or wood, connect us more than keep us apart.

Lebanon, bordered on one side by the Mediterranean and on the others by olive, orange and wheat fields, may have complicated, if not outright thorny, official relations with its neighbours today. But the relationships nurtured by people are different. By their very essence they traverse borders, and connect what is on one side with the other.

There is also a distinct neighbourly culture within Lebanon, which connects people living in the same street or building: a culture of chatting, sharing and helping one another. Some might argue that this is fading away with time; that close neighbourly relations are something of the past. Either way, there seems to be an inherent nostalgia associated with the concept of neighbours, and we are interested in finding out its current relevance.

The seven stories in this series on Neighbours, all written or produced by former participants to our workshops on journalism and writing, set out to do that.

First out is the tender memory of Sarah Khazem of early morning rituals with a temporary next-door neighbour; following that is Abby Sewell’s conversations with Syrian activists on the revolutionary events in Lebanon. Layla Yammine’s meeting with an antiques dealer in Beirut’s Basta neighbourhood comes third; fourth is Andrea Olea’s notes of kitchen conversations with two Palestinian friends.

Hamoud Mjeidel then takes us to the families residing in Umm Ali’s building in Shatila, and Ghadir Hamadi invites us to hear her family history spanning Lebanon and the Gulf. Rayan Sukkar and Samih Mahmoud, finally, brings us voices from those who may be considered neighbours of the ongoing Lebanese uprising.

As I walked into the Shatila camp, I could see fruit and vegetable peddlers lined up left and right, enthusiastically shouting out the price and quality of their products, competing for buyers.

In the midst of it all, a frail old man caught my attention. He was seated at the edge of the sidewalk, next to his vegetable cart, keeping his hands in his pockets to stay warm in the cold weather.

I went up to him, both to ask about the price of his fruit and the directions to my new place of work.

“Sir, why don’t you shout out your prices, write them on a piece of cardboard, or something?” I said.

“My son, God gives us our daily bread. And besides that, I am no longer in good enough health to yell,” he replied.

“My son, God gives us our daily bread. And besides that, I am no longer in good enough health to yell.”

Since that day, I would see the the old man known as Hajj Ibrahim each morning on my way to work.

But one day, he us no longer there. A boy around 18 years old is standing in his spot, telling me that the 70-year-old Palestinian is sick and can no longer work.

A while later, I was to learn of the death of Hajj Ibrahim, who lost his battle against cancer.

But something he told me always stayed in my memory:

“Son, why don’t you rent a house in the camp? It is much cheaper than in other parts of Beirut. I’ll take you to a building owned by a woman called Umm Ali. She rents out for a good price.”

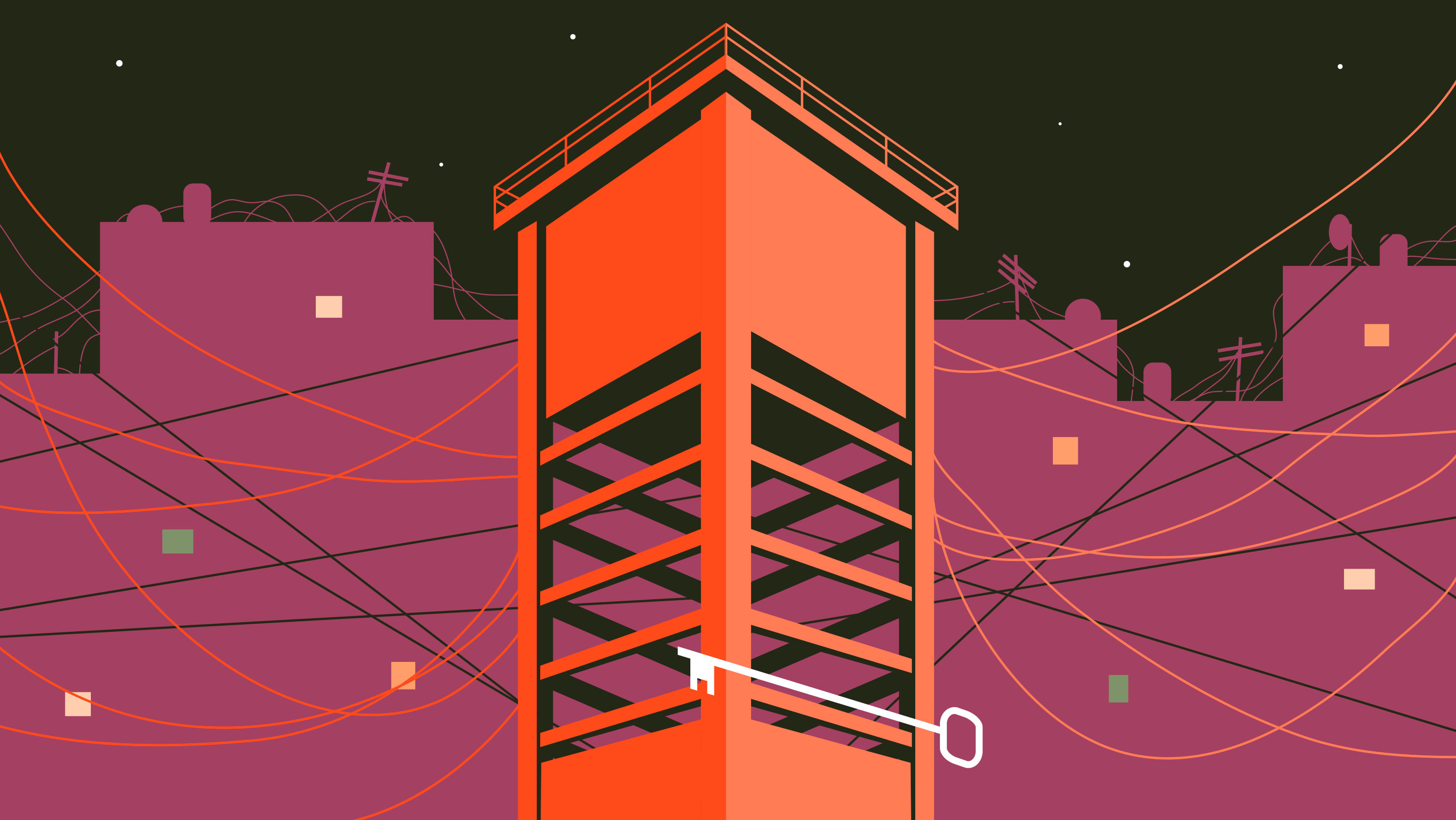

That day, I continue my way to work, passing by the power cables clinging on to the poles like spider web. I walk past pictures of the late Palestinian leader Yasser Arafat and the UNRWA tank, a large water tank with a key hung on it, symbolising the return to Palestine. When leaving their lands, Palestinian families took the keys to their houses with them, in the hopes that they would return one day.

When leaving their lands, Palestinian families took the keys to their houses with them, in the hopes that they would return one day.

Suddenly, inside one of the dark alleys, I reach an old building, over 20 meters high. It has four storeys and many small, simple apartments inside. This is the place Hajj Ibrahim had told me about: the building of Umm Ali.

The owner, a Lebanese woman in her late fifties known by the camp residents as Umm Ali, rents out her apartments at fair and reasonable prices, affordable for the many refugee and other families in Lebanon who live in poverty. Umm Ali, whose husband died a few years ago and children all live abroad, makes ends meet from the rent she gets. Herself, she lives alone in one of the apartments and maintains close ties with her tenants, all of whom come from different social, cultural and religious backgrounds. Some are Palestinians, others Lebanese, but the majority are Syrian families who fled the war.

“In the first years of the war, when large numbers of refugees arrived to the camp, many apartments were occupied by more than one family,” Umm Ali tells me.

“Some even slept in the yard of the building, as there was not enough room for everyone.”

Most of her Syrian tenants, she says, are workers who were already working in Lebanon long before the war.

“Many of them knew me from before. When they had to flee the war to Lebanon, they came to me with their families.”

Sitting in an old wooden chair in the open yard, I can hear children on their way home from a nearby school and the sound of vendors yelling in the nearby streets.

Sitting in an old wooden chair in the open yard, I can hear children on their way home from a nearby school and the sound of vendors yelling in the nearby streets. From one of the small windows of Umm Ali’s building I hear a baby crying, and the mother singing lullabies to calm the baby down. One of them is a song I know, the Arabic version of Hush Little Baby.

Sleep Ahmad, sleep,

I will slaughter a pigeon for you.

Go pigeon, fly away,

I am fibbing so that Ahmad goes to sleep.

During my years of working with a human rights organisation in Shatila, I have noticed the great deal of sympathy, compassion, welcoming and hospitality shown by Palestinians towards the refugees coming from Syria. Both people, albeit in different circumstances, share the same plight of displacement. Shatila, which was first established in 1949, is now home to many Syrians without residency papers, who are unable to work legally outside of the camp. Many live on limited incomes, including from jobs like selling vegetables from carts in the street.

Wandering around the streets of Sabra, you now see many shops selling clothes typically worn by Syrian women from the countryside around Aleppo, Deir Ez-Zor and Raqqa.

Sabra, the nearby market, has also become more filled with people, peddlers and shops than before. It is cheaper than many other markets in Beirut, so many Syrians come to Sabra for their shopping. Wandering around its streets, you now see many shops selling clothes typically worn by Syrian women from the countryside around Aleppo, Deir Ez-Zor and Raqqa, including the kalabiya, a long garment decorated with embroidery.

Places offering Syrian food have also mushroomed in and around Shatila, taking their names after the Syrian cities where their owners come from. There is Aleppo Kebab, Idlib Shuaibiyat (which offers a traditional kind of sweet from Idlib) and Sham Sweets, among an array of others.

It was from Sham – or Damascus – that Umm Ali’s very first Syrian tenants came, during the early days of the war.

“I was at [the] Ramlet al-Baida [beach] with my neighbour, Umm Muhannad, one day when I saw a family gazing at the sea. It was a woman in her forties, her husband in a wheelchair and their two children, a 10-year old boy and a girl who was barely eight. They just sat there in silence, except for their children who were playing in the sand. I was curious to find out more about this family and why they were sitting on the beach for so long. So I approached them,” Umm Ali recalls.

“I asked them: ‘Why don’t you go back to your house, the sun is scorching and might hurt your children?’ The woman told me, ‘What house? We don’t have a house to go back to. We arrived in Lebanon at dawn today, after fleeing the war in Syria. Our house was destroyed and we have nowhere else to go’.”

“We arrived in Lebanon at dawn today, after fleeing the war in Syria. Our house was destroyed and we have nowhere else to go’.”

Umm Ali continues.

“I remembered that there was a small room in my building, so I told the woman – her name was Fatima – ‘Get your husband and your kids and come with me.’ I hailed a cab, we picked up their modest bags and drove back to the camp. They were the first refugee family I took in in my building.”

A cold breeze interrupts Umm Ali’s story for a moment, and she asks that we move inside. There are photos of her sons working abroad in the house. As she talks about them, she agrees that it makes her feel sad. But not lonely.

“My neighbors are always by my side, which makes it a bit more bearable,” she says.

“My neighbors are always by my side, which makes it a bit more bearable.”

Among those neighbors is Dalal, a 37-year-old Lebanese woman and one of the first residents I got to know from Umm Ali’s building. When we start speaking, she immediately mentions her friend, Sahar.

“Sahar is no longer here, she left when she got the chance to get asylum in Canada. I spent most of my time with her. We talked about politics, and more often than not, we disagreed on what was happening in Syria. But with time, I learned to accept her opinions,” Dalal says.

“We talked about other stuff too. Sahar taught me how to make malihi, a traditional dish well known in Daraa where she is from.”

Fatima, the woman from the beach, comes and joins the conversation. She holds a bag with vegetables from the market in one hand, and the hand of her daughter in the other.

“The yard of Umm Ali’s building has become a meeting point for all tenants, where we listen to each other’s stories and talk about our daily problems,” she says.

“The yard of Umm Ali’s building has become a meeting point for all tenants, where we listen to each other’s stories and talk about our daily problems.”

“Each one of us comes from a different area, so we have come to know about different cultures and traditions. Even those of us who are from the same country realised that we knew nothing about each other’s social and cultural traditions.”

She continues.

“We also talk about politics. The discussion sometimes get heated, and our neighbour Umm Saad might get angry and leave the place when we talk about a politician she supports. But as the days pass by, we learn to accept each other whatever our opinions.”

Just like Dalal, Fatima talks about how she has adapted new ways of cooking in Shatila.

“I have learned how to cook many Palestinian dishes, including molokhia, musakhan and bissara with beans and chickpeas, and a couscous dish called maftoul made from chicken, chickpeas and veggies. And rummaneyye, prepared with pomegranate, lentils and eggplants,” she says.

During Ashura one year, she says, the tenants commemorated the Shiite holy day together.

“My neighbors and I helped Umm Rida, a Lebanese woman living in the camp, to prepare the chicken and wheat dish harees, traditionally served in Shiite homes. After we finished cooking, Umm Rida distributed the food to the children and women in the building. My children were holding up Shiite religious banners, even though we have different [religious] beliefs. But since Umm Rida was my neighbour and we were on good terms, I took part in this occasion.”

“My children were holding up Shiite religious banners, even though we have different [religious] beliefs.”

Umm Ali too says that many tenants and families living near her building honour new relationships.

“The children run and play in the small yard every morning, because there is no other safe place in the camp for kids to play. In the afternoon, women sit together – some of them have just finished work, others have come back from the market. And in the evenings, men smoke their hookahs until late at night. During the weekends, everyone sits together,” she says.

She has many examples of neighbours supporting one another. Mariam, a single Palestinian woman who worked in a sewing shop used to live in the building with her children.

“One day, one of her kids got sick. The doctor ordered an abdominal X-ray, but she could not pay for it. So all the women pitched in and secured the money. We help each other every time one of us faces a difficulty,” Umm Ali says.

Then there was Hanaa, a woman in her forties from Idlib, who used to face her husband’s resistance to her getting a job to cover for the family expenses. Finally, she managed to convince him, after hearing from a neighbour about a vocational training to learn sewing and embroidery.

Hanaa gifted Umm Ali an embroidered purse, with the motif of a car with luggage packed on top, coupled with the expression: “Away from home”.

After the training, Hanaa gifted Umm Ali an embroidered purse, with the motif of a car with luggage packed on top, coupled with the expression: “Away from home”.

Listening to all of these stories from Umm Ali and her residents – Fatima, Sahar, Dalal, Mariam, Umm Rida and Hanaa – made me realise just how much a simple, random building might bind together those who come to stay under its roof. Or, as the Palestinian poet Mahmoud Darwish said:

“Without memories you have no real relationship to a place.”

Neighbours was produced as part of the 2019-2020 Switch Perspective project, supported by GIZ. All illustrations by Ismaël Abdallah.