Vanishing act

Tearing down the Mayakovsky theatre

The Tajik government wants to tear down the fabled Mayakovsky theatre. But it’s not going anywhere without a fight.

To many residents of Dushanbe, Tajikistan, the Vladimir Mayakovsky Russian Drama Theatre is an icon of the city’s illustrious past. The notoriously pink theatre, standing in almost the exact centre of the city, has been home to Tajikistan’s premier Russian-language theatre company for nearly 80 years. Yet despite popular protests, the Tajik government has moved forward with a plan to demolish the theatre by the end of 2016, potentially signalling the theatre company’s demise – and the end of an era.

The company was relocated to a temporary home on May 1. But until that very day, the show went on. One afternoon only few days before the venue’s closure, its stage reverberated to the sounds of Elvis and John Travolta; Masum, the theatre’s sound technician, was checking the levels ahead of a party honouring a national poet.

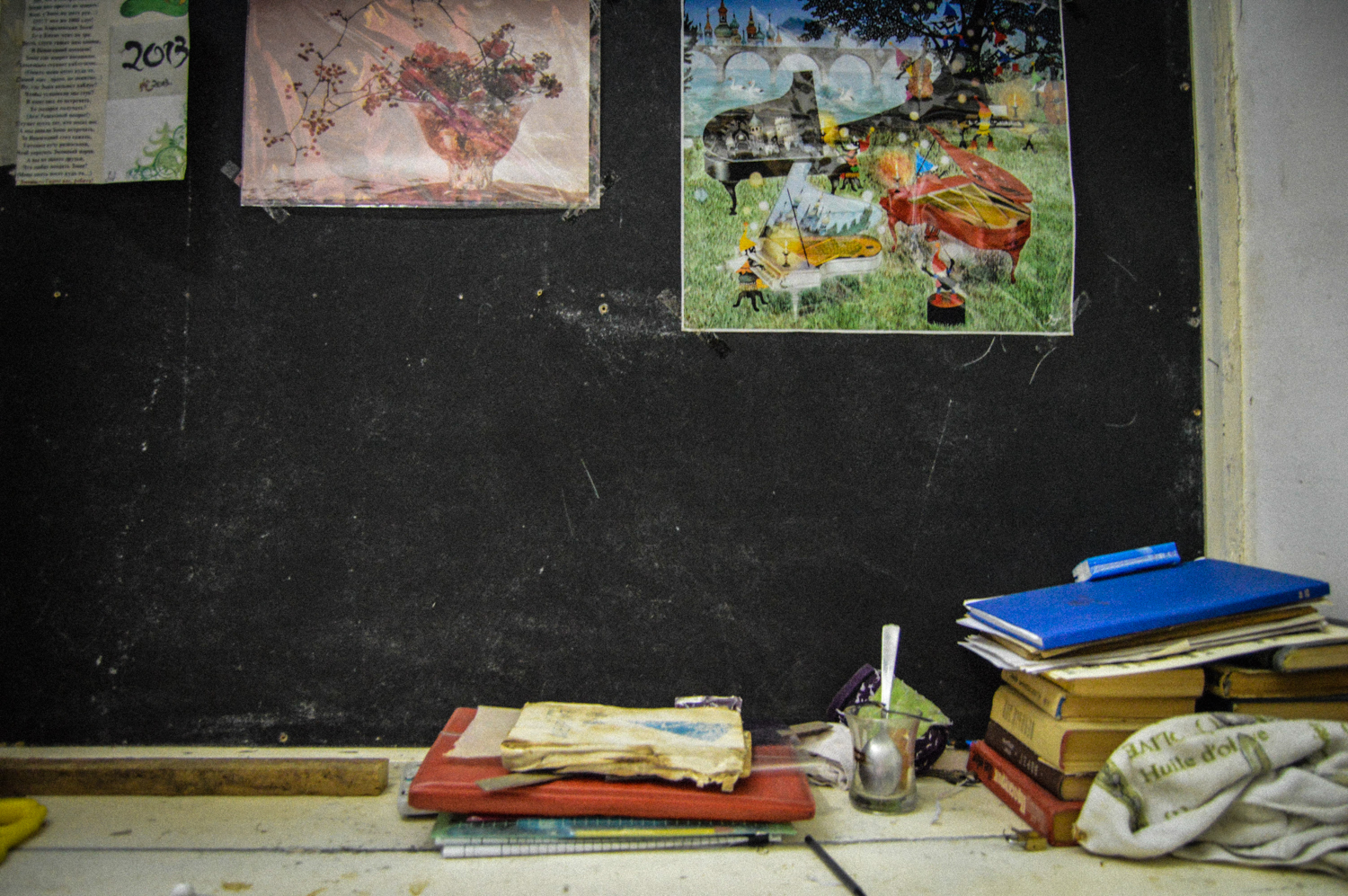

In a second-storey classroom, teenage participants in a youth acting class alternately preened and paced, muttering memorised lines. Narina, a props technician, and her mother, who works in the costume shop, pressed and hung many-layered Georgian gowns and tall papakha hats used in a production the night before. Stagehands, actors and an assistant director worked together to uncover the boards, hang curtains and find set pieces.

That day, the theatre was full of life.

That same day, Kristina, an actress, was busy storing props. She joined the company right out of high school seven years ago and is married to Anton, a stagehand. The theatre is built like this, around families: Narina in the props shop was preceded by her mother, whose own mother worked at the ticket counter.

Theatre Director Munira brought her two-year-old son with her to work; as he tottered down the corridor, Deputy Director Gulnora spied him and swept him up with a kiss.

The theatre employs over 90 people all told and it feels very much like one big extended family.

The government plans to move the company temporarily to an empty cinema, far in the southwest of the city, while construction on what promises to be the biggest drama theatre in Central Asia moves forward. When that theatre is finished, the Mayakovsky company is slated to move there. So far, every actor has sworn to remain with the company.

To many residents of Dushanbe, Tajikistan, the Vladimir Mayakovsky Russian Drama Theatre is an icon of the city’s illustrious past.

But work on the new theatre hasn’t started yet and the construction timescale is unknown. If ticket sales at the temporary venue are slow, Kristina says, actors may choose to look for work elsewhere. The move to the cinema is a slap in the face; not only are the facilities inadequate, but the location is out-of-the-way and difficult for even regular attendees to get to, let alone tourists. If enough company members leave, for work in theatres in Russia or elsewhere, the Mayakovsky company may be forced to dissolve entirely.

The old building’s interior is dim, and well worn, and fussily decorated with plastic faux-wood floors and thick red velvet curtains. The theatre itself is strangely narrow to modern sensibilities – only two sections on the main floor, a mezzanine and a total of 350 seats.

The stage boards are unplaned and creaky; the seat cushions are bald and shiny from decades of bottoms. Costumes and props are piled perilously; dust gathers in dark corners around globs of thickly applied paint. The building’s low-slung façade and closet-like foyer stand in sharp contrast to the ranks of homogeneously blue-windowed high-rises that have begun to punctuate the city in the past two or three years.

The government of Tajikistan has proclaimed the theatre will be torn down in line with a “master plan to reinvent the capital city,” introduced in the autumn of 2015, according to the Asia-Plus news agency. “The buildings that will be demolished have no historical uniqueness. These are buildings that are in very bad condition,” Nurali Saidzoda, the chairman of the Construction and Architecture Committee, told Silk Road in October. “If you saw the new buildings that we are planning to construct, you wouldn’t be asking all these questions.” The plans of the new buildings remain classified.

Critics say the government’s real intention is to wipe remnants of the city’s Soviet history from the map, replacing historic neoclassical buildings with new apartment complexes funded by entrepreneurs hoping to curry favour with the new regime. City planning officials “are victims of their own crassness, vulgarity and shortsightedness. It is impossible to contemplate the illogicality and conceptual squalidness of the buildings that have gone up in Dushanbe over the last five years,” Anisa Sobiri, a well-known Tajik writer and poet, told EurasiaNet.org.

“The buildings that will be demolished have no historical uniqueness. These are buildings that are in very bad condition.”

In a surprising display of public resistance – protests in the autocratic state are few, far between and quickly silenced – since October 2015, 1,185 Dushanbinci have signed an online petition protesting the destruction of the Mayakovsky Theatre and other well-loved Soviet-era buildings. Anti-destruction sentiment abounds on Facebook, Twitter and the Russian networking site Odnoklassniki. Actors have been begging audiences at the close of shows to help save the theatre.

The protests may be the theatre’s lasting legacy in the modern age.

On April 27, Anisa Sobiri, sparked by the government’s refusal to consider public sentiment against the destruction of the theatre, published a diatribe of an op-ed in the underground opposition newspaper Ozodagon: “My country is afraid of radical Islam while destroying the theatres, museums, erecting instead tasteless, terrible, pointless buildings, which refuse to host any events if you don’t pay a fee… I only want to live in Tajikistan, but it’s impossible to live in Tajikistan.”

In a last-ditch effort, the prominent historian Arkadiy Dubnov has appealed to the Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs to intervene on the theatre’s behalf; surprisingly, the MFA took him up on it, but to no avail.

Such recent protests hint at how dearly Dushanbinci hold the Mayakovsky Theatre as an emblem of the city’s Soviet cultural heritage. The protests may be the theatre’s lasting legacy in the modern age, rivalling the Mayakovsky’s golden years in the 1970s and 1980s, when its company toured the USSR to acclaim, and its resurgence in the early 2000s, when a performance in Paris was saluted by a 40-minute standing ovation.

But Tajiks’ rallying around the theatre has a tragicomic element to it: it’s not often that the plans of iron-fisted dictators are thwarted by petitions and public appeals. Likely, it will be too little, too late. Likely, the Mayakovsky Theatre will vanish, without a final curtain call.

Katherine Long first published this text and the photos on her site Rohro. Helen Southcott and Stephanie Watt edited.