Looking for the lost bus

In just six years of existence, the Lebanese NGO UMAM D&R/The Hangar has succeeded in making the southern Beirut suburb Haret Hreik an epicentre of cultural life in Lebanon. Not content with having established the country’s first archive with “essential materials from Lebanon’s past,” UMAM’s founders, Lokman Slim and Monika Borgmann, regularly hold exhibitions which similarly pose questions and challenges to the Lebanese collective memory.

A year ago, they organised Missing, an exhibit displaying photographs of hundreds of individuals who vanished during the Civil War, breathing new life into the national debate on disappeared persons. A few months back, they store the entire historical archive of the Carlton Hotel prior to its demolition.

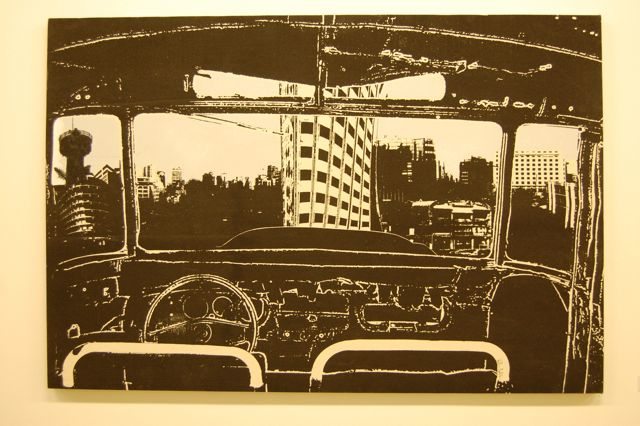

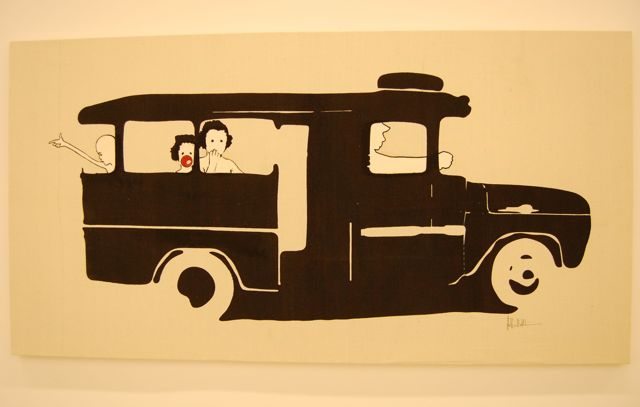

Their latest shock to the collective memory: Finding the bus from the Ain El Remmaneh attack which sparked the Civil War, and exhibiting it at the Hangar. “A Bus and its Replicas” is UMAM’s first exhibition concept with collaboration between an artist and the archival collection.

The exhibition occasioned Lebanese painter Houssam Bokeili’s first foray into the medium of silkscreen, while Monika Borgmann became an impromptu bus detective. Mashallah had the opportunity to interview the artist and the archivist in Beirut.

Did Lebanese people know that the Ain El Remmaneh bus still existed somewhere in Lebanon?

Monika Borgmann: Not really. I know that there were exhibitions held in the past which involved the bus, but they always used replicas. Houssam wanted to do a show where he would work on the theme of the school bus. In the end this became the exhibition concept: when the school bus, symbol of a happy childhood, is interrupted by the collective symbol of the ‘war bus’. The Lebanese are extremely divided on the subject of the Civil War, but the bus is the only symbol that everyone can agree on. Past that point, they stop agreeing. Were the Palestinians sitting in the bus armed or not? Things like that. The bus is the official symbol of the beginning of the Civil War. We could easily have chosen another date — there was violence before April 13, 1975 — but it is the attack on the Ain El Remmaneh bus which became the official date.

How did you manage to find the bus?

Monika Borgmann: We started out wanting to reconstruct its history. In the end, we found an interview with the bus driver in our archives, in a film about the Lebanese Civil War. We wondered what had become of him. The driver had died but his son was still alive, and we met with him. This was the first time he gave someone the police report on the attack. Around the same time, we found the name and telephone number of the current owner of the bus. By pure coincidence, he lived in Ghobeiri, just across from the UMAM offices! He had kept the bus in the countryside, in a meadow near Nabatieh in south Lebanon. It was completely rusted — it had spent 15 years outdoors without protection.

You then transported it from Nabatieh to UMAM for the exhibition?

Monika Borgmann: Yes. It was an amazing experience to bring it from the south to Beirut. It was already dark when we hit the road. We drove with the bus in tow and the whole time we were asking ourselves what the people passing us could possibly think or imagine about our cargo. It was really a very special moment. And when we got here, we had a crane take it over the wall of the Hangar. The whole neighbourhood immediately crowded around — they were in a state of shock. They were asking “is this the bus from Ain El Remmaneh?” They wanted to touch it to be sure. One woman even told us, “my son died on that bus”. I am sure it was not true but she must have said it in an effort to appropriate the bus. It was physically palpable.

When were you sure it was indeed the bus from Ain El Remmaneh?

Houssam Bokeili: It was simple: when we saw the confrontation, the conflict between the current owner of the bus and the driver’s son, there was no further doubt. The son of the driver, visibly upset not to have inherited the bus, said to the current owner: “But why are you talking about my father? You do not know my father, it is our history.” The son very much regretted that the bus did not pass to him.

Why didn’t he inherit it?

Monika Borgmann: The history of that bus did not stop on April 13, 1975. Surprisingly, the bus survived the attack, as did the driver — who owned the bus — and he continued to drive it afterwards. Except that a few years later, also in April, during a later phase of the war, the driver parked his bus outside his home and it was hit by a shell. The driver’s wife then forced him to get rid of this bus that was attracting so much evil. The driver agreed to sell it, and that is how the current owner found it in a garage in Beirut some 15 years ago. He first bought it without knowing it was the Ain El Remmaneh bus; then, he left it to rot in a field in the countryside.

What kind of reactions have you observed among visitors?

Houssam Bokeili: Some people cannot believe that it is the real bus. A young woman said to me: “I was told that the bus was here, and it did not affect me at all until I saw it.” That is the real issue. It begins to really hit you that it has been 36 years. And, its presence forces you to wonder about the present and future: is the war over or not? Are we moving towards a better future, a stronger society? We also had visits from many schools, and all the teachers we met were very engaged in these questions. Sometimes when children see the bus, they are afraid because they did not expect to see it in this state after all these years, rusted to the marrow.

There is no official date marking the end of the war. So every year, commemorations are held on April 13. How do you commemorate — without celebrating — the beginning of the war?

Monika Borgmann: We had planned to open the exhibit on March 25 and close on April 13, to sort of ‘wink’ at that date. But Houssam, who had to print the silk screens in Cairo [where he lives part time], was held up because of the revolution, and that pushed the exhibit back several weeks. In the end, we opened on April 8. We wanted to somehow link the exhibit to April 13 while at the same time remain independent of that date. I never wanted to open on April 13, I do not like the idea of celebrating the beginning of the war. Because there is no official end, we only speak of the beginning of the war. The Taif accords ended the fighting, but without really signalling the end of the war. That date is still not really clear.

What will become of the bus at the Hangar?

Monika Borgmann: For now, the owner does not want us to sell it. It will remain in the Hangar until May 1 and then we will put it in the garden. Later, we’ll see. We will also soon be launching our new website, the first virtual museum of the Lebanese Civil War. We want the participation of the Lebanese people. From June, we’ll be travelling throughout the country to promote awareness of this website. We have also started to collaborate with other artists on the theme of the Civil War. The new policy for the Hangar is to link art and archives to a greater and greater extent. Because, by ourselves only, we cannot render them accessible to the public.

2 thoughts on “Looking for the lost bus”

Comments are closed.