The end of orientalism as cultural currency

By bursting the bubble of mainstream discourse, there is no doubt that the Gezi protests transformed the horizon of grassroots political praxis in Turkey. Should we expect as equally drastic a change in the domain of culture and the arts? After Gezi, is it still possible for the cultural industry to cling on to the easily marketable “self-Orientalising” currency that has been so fashionable over the past 10 years?

Just as in other intellectual geographies, Turkish thinkers and cultural actors have always been fond of dipping into debates around identity matters. The main split of consciousness that gnaws away at the question of Turkish identity is considered to bethe tension between an “imposed Westernisation” and a “repressed Oriental identity”. In the eyes of many, the collateral damage caused by the from-top-to-bottom modernizing ardour of Kemalism had resulted in a tremendous cultural wealth being swept under the rug of a makeshift modernism.

But this very idea of a dichotomy was mostly unaddressed until the AKP’s ascension to power in 2002, which brought to the fore a new globalist political agenda that hoped to introduce a post-modern, moderate Islam. Tearing down every policy that belonged to the ancien regime, Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s iconoclasm also bred a new intellectual atmosphere within which this “repressed” Oriental identity – which was at odds with forced Westernisation — was able to re-emerge.

[/et_pb_column][/et_pb_row]

From this collective subconscious erupted eager explorations of the possibility of modernism to rise from the East. This was reflected in continuous condemnations of the legacy of the oppressive cultural policies of Kemalism. Although the country’s belonging to the East still remained in question, from Nobel laureate Orhan Pamuk’s playful meditations on the rupture of the Turkish historical consciousness to Elif Shafak’s elegies to bygone Istanbul cosmopolitanism, a nostalgia revolving around the Ottoman past became a popular theme in in the arts and literature as well.

The inflow of international capital along with the peaking interest of the national big business in opening arts spaces and museums (from the opening of an Istanbul chapter of Sotheby’s to the popping of a variety of museums, the symptoms were plenty), highlighted Istanbul as an emerging nexus of culture and arts stemming in part of the financial developments Erdoğan was so proud of. This pride was boundless that he even declared that the global economic crisis would “pass at a tangent to Turkey”. After 2006, “Cool Istanbul” was the name of the game: Turkish artists found themselves on the A-lists of international buyers, and corporate-sponsored museums sprouted all over the city. Istanbul was, finally, taking solid steps towards becoming the new “It” city of the Middle East.

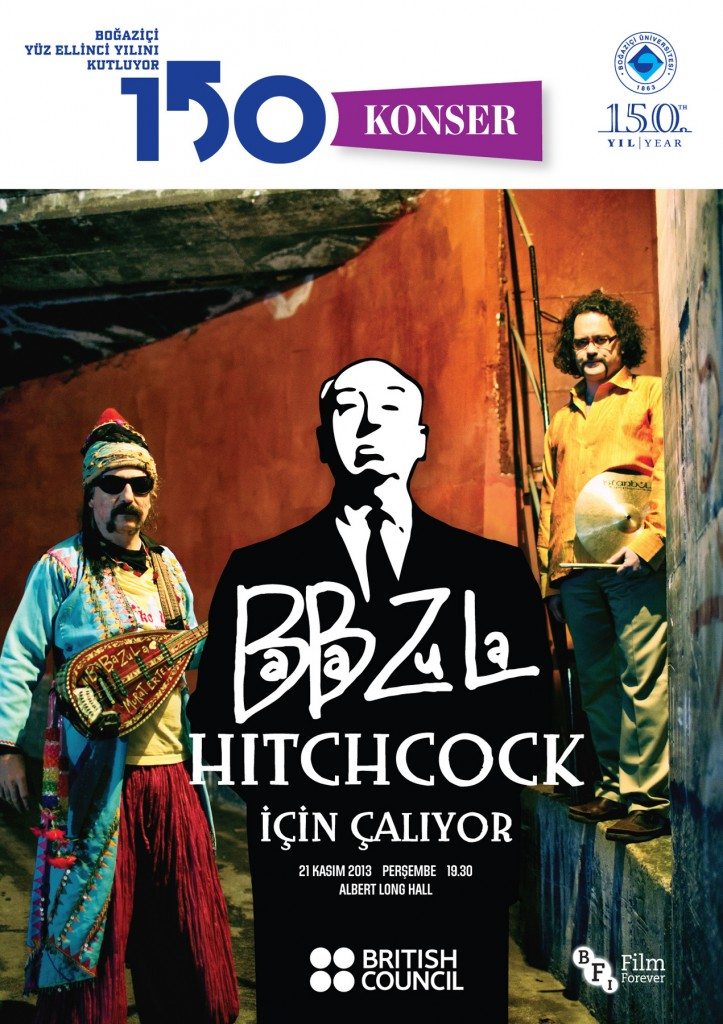

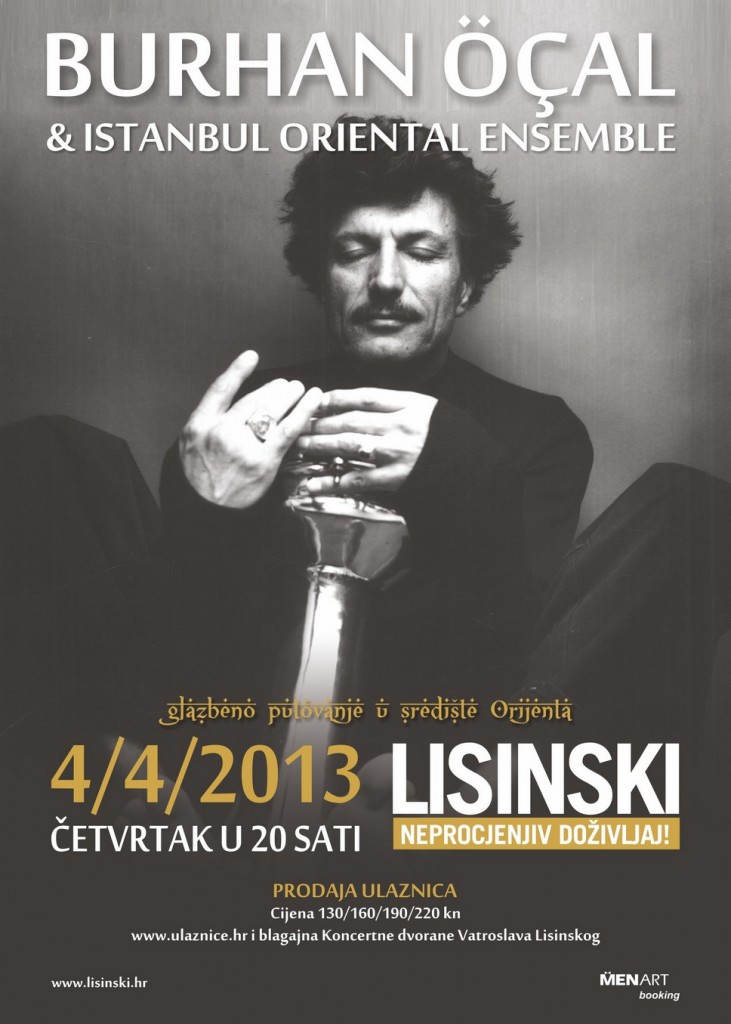

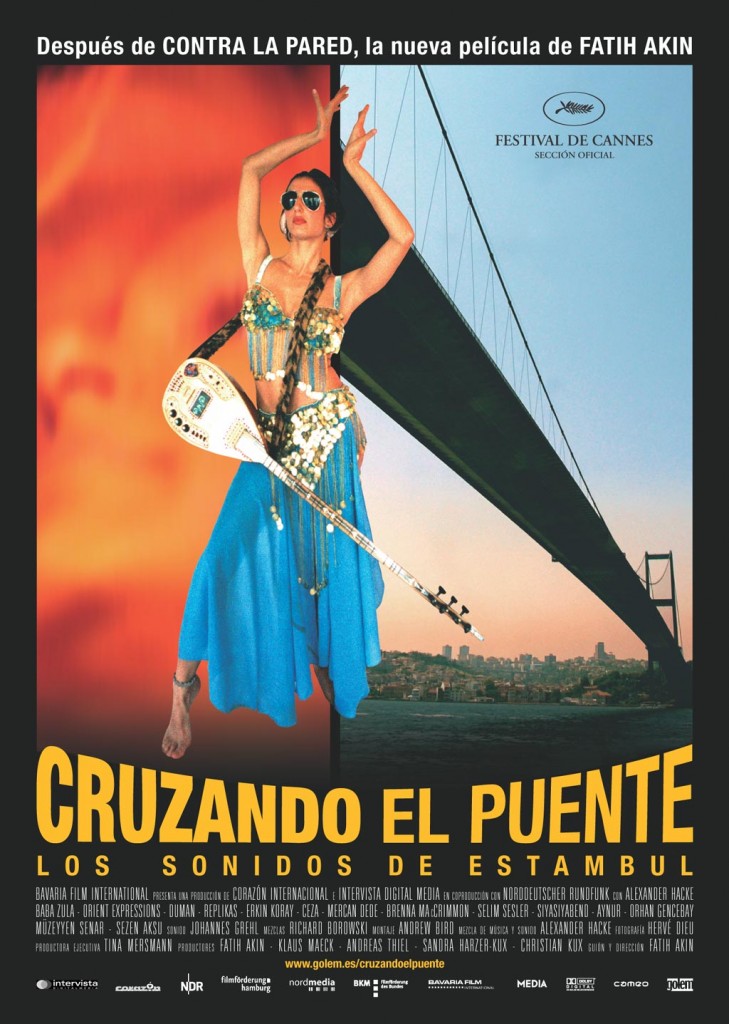

Music had its share in the fever, too. The pop music front welcomed the so-called “New Sound of Istanbul,” a label applied to a group of artists investigated by Fatih Akın in “Crossing the Bridge”. This wave was carried forward by bands such as Baba Zula and Replikas, who sought to pay homage to the creativity of 1970s Turkish psychedelica. Turkish expatriates such as Swiss resident and percussionist Burhan Öçal or New York’s İlhan Erşahin, famous for their personal “East and West” syntheses, were already at the forefront of Turkish cultural production abroad.

The government, of course, was hardly as open-minded as the cultural actors they keenly advertised abroad with numerous cultural openings from the big “Turkish Season” in Paris to strings of Turkish Film Weeks in European capitals.

AKP spokespeople did not hesitate to pop remarks about the “double standards” of the West, using arts and culture as background noise to their revanchist and nationalist rhetoric. However, they were seemingly unaware of the fact that, as far as the relatively urbanised and Westernised consumers of culture were concerned, they had almost none of the “soft power” they enjoyed in the Balkans and the Middle East. Yet, even the duplicitous Istanbul Capital of Culture could not ruin the celebratory atmosphere.

A nostalgia revolving around the Ottoman past became a popular theme in in the arts and literature as well

Hybridity, metissage, synthesis, cosmopolitanism, glocality, East versus West, Islam versus modernity. This is what the bulk of Turkey’s artists was almost obsessively fixated on up until 2013. In reality, everybody was well aware that this overdue celebration was driven in part by the power of the discourse of globalism, and that the excitement might well have an expiry date. The most mainstream spill-overs of this soaring cultural production had a story to tell.

Sertab Erener’s Eurovision performance in harem girl garments, embodying the ages-long objet du desir of Orientalism and the Anatolian Fire dance shows that marketed the image of Anatolia as the abode of fraternity were more obvious examples. On the more latent side, Mercan Dede’s Sufi-Electronica synthesis made the most out of the Western fascination with Rumi and Sufism while raising questions about authenticity. Yet, many indeed proved that the substance of the renaissance of Turkish cultural production was as touristic and as self-orientalising as the belly dancing dinner shows in Galata where tourists pay for watching what they think represents a great part of Turkish culture.

However, few seemed to bother when Turkish culture was getting its rightful share of international attention.

Then, one auspicious day in May 2013, while the AKP was getting ready to put an end to the “Kurdish question”, the bubble burst. During the course of the last couple of years, the mind-set that had dictated the AKP’s decisions had already come into question — mainly due to Erdoğan’s increasingly hostile and alienating remarks and actions directed against various groups, including a significant part of society that was worried about seeing its freedoms usurped by a government with authoritarian ambitions under a liberal disguise. While eight years ago Erdogan seemed to have convinced the crowd that he had changed and had left his radical tendencies behind for a moderate “conservative-democratic” stance, the show he put demonstrated that the masquerade was over.

Spreading like wildfire to almost every part of the country, the energy unleashed by the Gezi Park protests shattered the last remnants of the AKP’s tolerant and moderate façade. The outcome — nine dead and thousands wounded — revealed the scale of Erdoğan’s hubris as well as the pathetic state of the Turkish mainstream media with regards to upholding journalistic ethics and standards. While parts of Istanbul were literally burning, major TV stations, including CNN Turk, the Turkish partner of CNN International, opted for airing TV series or documentaries of arctic wildlife (or in the case of another major TV station, an interview with the president Erdoğan himself where the interviewer did his best to condemn the protests).

What Gezi functioned as was a sort of magical moment when the hypnosis wore off and people woke up from their decadent dream: Istanbul had, beneath its cool façade, been turned into the AKP’s experimental playground, upon which it was determined to erect a cement dystopia — a flawlessly gentrified neo-liberal haven. When the protests were spreading, the demolition/gentrification of Tarlabaşı — a marginalized European side district — was going on to top up the string of urban renewal projects AKP launched. With an urban development credo that dictates the popping up of newer, shinier and vaster shopping malls at every corner, AKP had been more than allergic to green spaces. However, like the protesters repeated a million times, Gezi was not about a bunch of trees — Erdoğan’s insisting to raze the tiny green breathing space that was Gezi was only the last straw that broke the camel’s back. More shockingly, faced with the danger of instability caused by the acts of the government, the global cash-flow that once was instrumental in creating the buzz around Cool Istanbul could stop pouring into the country in a second. How could a government that now acted with such reflexes be in any position to inspire a renewal in the domain of culture?

Fed by genuine emotions and attitudes, the Gezi Park protests seemed to represent an eruption from below, and became the stage for some stunningly diverse artistic performances. The performances themselves — flash mobs, resistance anthems or impossible-to-index manifestations of instantaneous creativity on the streets — could certainly not usher in a new era by themselves. This explosion, which was impossible to tuck into the confines of any clean-cut political path, did not come with a manifesto or aesthetic dictum of its own — Gezi was rather an alliance of the unhappy cemented by feelings of mutual respect and solidarity. However, as the protests dissolved the shroud of the AKP zeitgeist, they raised questions about the need for new directions in the domain of culture.

The Aesthetics of Resistance exhibitions hosted by a handful of galleries in Istanbul (located mostly outside the circuit of the European side) could demonstrate how tame, tedious and uninspiring institutional art has become. In the end, the dialogue that was so fervently circulated about the East and the West was only tangential to the reality. Even the Gezi playlists, which were compiled by various publications can demonstrate the lust for life the unyielding creativity of Gezi embodied. From Boğaziçi Jazz Choir’s protest hymns to Dubstep anthems, the music in those playlists was challenging, irreverent of dull categorizations, almost always full of caustic humour and most importantly, re-defining the boundaries of protest music in the Turkish climate.

In essence, what Gezi showed was that there was a specific room in the urban reality, in the contemporary era we live in, for genuine, defiant and fresh art that does not seek to be amplified by global agendas or governmental ambitions. Self-Orientalizing rumblings, from the kitschiest to the more serious, though seemingly tough on the oppressive modernism within, are bereft of a solid critical angle. They cater to an audience (and desire to create one in the absence of it) which seeks to engage in barren dialogue with a limited understanding of the vastness of culture and the state of politics: the discussions that popped up around the particular subject of East and West were obfuscating, rather than mind-opening.

Engaging the now, on the other hand, can be more rewarding than obsessing over identity matters — or whatever is served as food for thought by the global succession of trends. It may be a truth forgotten long ago but art can remain caustically critical. It can shake and inspire the masses without reverting to populism or kitsch.

6 thoughts on “The end of orientalism as cultural currency”

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

“Gegen die Bridge”, “NO Egzotik NO Touristik“, „No Dialogue“ (2/5 BZ, 18 January 2011 ) – See more at: http://norient.com/stories/25bz/

Thank you for this brilliant article.