Algerian stampede

An interview with Sofia Djama

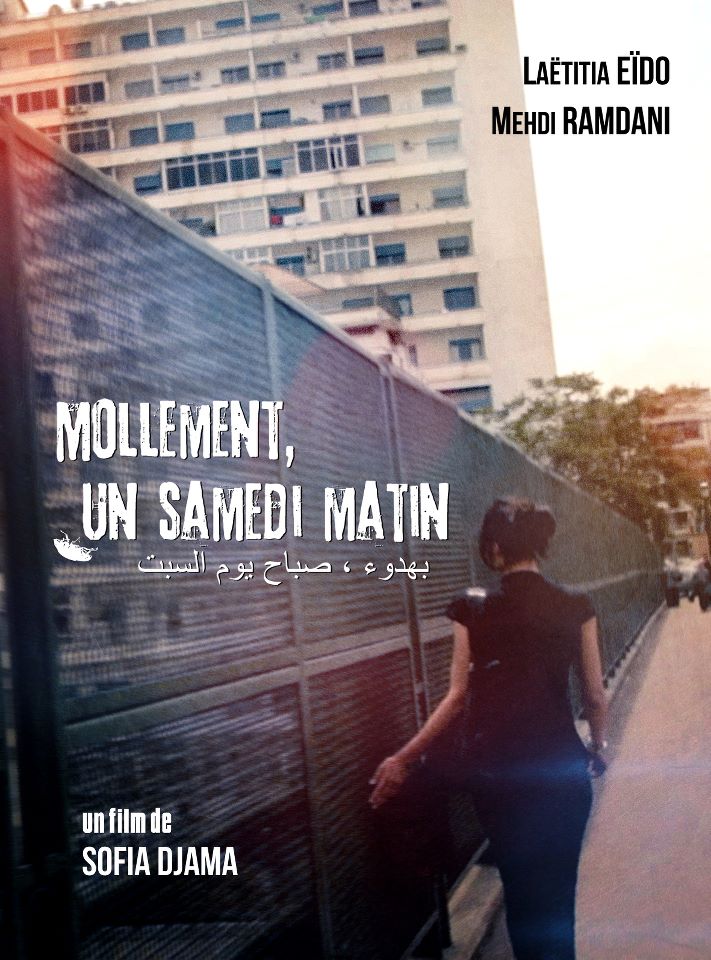

One evening in Algiers, Myassa returns home late. In the hall of her apartment building, she is overwhelmed by a stranger. But her presumed rapist — powerless — is incapable of completing his horrible plan. At home, Myassa discovers that the water has been cut off. Her next morning starts with two priorities: to find a plumber in order to finally be able to shower, and to file charges. Then, accidentally, she stumbles upon her aggressor in a bar.

“It is a film about society, a society in which everyone is unhappy — even the men.”

Algerian director Sofia Djama’s debut short film Mollement un samedi matin (Gently one Saturday morning) is a chronicle of a country in crisis. The film was shown on Arte last February and awarded a prize at the Clermont-Ferrand International Short Film Festival. Mashallah News got to speak with Sofia, who recounts her love of cinema and comments on the opposition to change within her country.

How did you start working with film?

I was born in Oran and raised in Béjaïa. I studied there for two years at university, at the Foreign Languages and Literature Department, before I finally left for Algiers. When I arrived in Algiers in 2000, the land was coming out of more than ten years of civil war. People assumed the war was over even though there were terrorist attacks all around the capital. So people were leaving in large numbers then, and expatriates had also started arriving during that time; you would meet them in the nightclubs. It was a period of decadence, of tearful reunions with life.

I always wanted to make films. But because of the civil war, there were no more film schools in Algeria. So I became a publicist. I worked for Publicis and other multinationals. In fact, there were very few films being made at that time, especially films set in places like Tunisia or Libya. It was a very exciting time in the beginning, but it wasn’t encouraging.

“It was a period of decadence, of tearful reunions with life.”

So I did what I did best: I went to see films, especially at the film club of Algiers’ cultural association called Chrysalide. In 2003, I wrote a group of short stories bringing together several titles which portray different characters during their nightly tribulations. The film is called Wednesday and a half, A Quarter To Thursday, A Perfect Friday. Then, Gently One Saturday Morning, which I adapted into a screenplay, came in 2006. At that time, a wall of silence had once again fallen on Algiers. Within two years the city had become oppressive.

Where did this change come from?

A new social morality has been established. A strong sense of guilt began to emerge in one’s relationship with pleasure. Algerians are very austere people. This can be explained by a frustration which is generated by politics. From 1962 until today, Algeria as a country has never broken with religion. Our society has taken as a reference point religious archaism, and fits that into a patriarchal regime. The civil war was a war against Islamism, sure, but not against this idea of religious archaism, which the state wants to maintain. The Algerian state has at its disposal the Ministry of Religious Affairs, a state institution that is being used for preaching. The imams are workers of the state, charged with fighting against Islamism.

For example, to not observe Ramadan is not actually punished by law here. The beaches remain open and there are lifeguards. But the Ministry of Religious Affairs nevertheless announced that it was not desirable to go to the beach during Ramadan — the same way one should not question the price of greens during this period. This is a way for the state to completely put a sense of guilt in people. It’s the use of religion as an instrument.

“At that time, a wall of silence had once again fallen on Algiers. Within two years the city had become oppressive.”

Because the Islamists in Algeria, they no longer cut people’s throats. They sell underwear [this is in reference to a scene in Gently One Saturday Morning in which a bearded man in djellaba vends underwear in the street]. By now, we have so absorbed Islamism that it has become part of us. The worst of all is the man who taps me on the shoulder and asks: “So, are we going to fuck?” because for him, I’m a “liberated” woman. These are the people who are the most dangerous, those who give grand speeches on women’s rights but don’t let their sisters leave the house.

It is incidentally this frustration that your film discusses.

Yes, there is an enormous feeling of frustration in Algeria. Algerian society is a suppressed society which is terrified of love stories. Even without religion, no one here takes pleasure anymore, except in the renunciation of pleasure. We renounce things little by little, we shut ourselves off. It’s about trying to be self-sufficient, but bitterness takes the upper hand and we become hardened. Everything becomes weak and unclear — even the opposition. You have to find a taxi driver who won’t make rude comments because you are going home so late at night. Young people in the street treat you like a whore. Every weekend is death, is gloomy.

So, by the sheer strength of things, I found myself doing what I had always denounced: living a life completely on the inside. In my film, Gently One Saturday Morning, we see no public spaces. The only glimpse of that comes at the very end, when we can see the sea and the horizon. Algiers is a city which has turned its back on the sea — you can see it from high up but you can’t touch it.

Algerian society envies but it does not desire. People cannot touch one another, so they start hating each other.

Gently One Saturday Morning is a film about society, a society in which everyone is unhappy — even the men. Myassa must fight every day just to exist. The young man who insults her in the street, how can you expect him to be an adult, a man, when he has no perspective of a future? He has no job, no place to stay, only misery on the horizon. Algerian society envies but it does not desire. People cannot touch one another, so they start hating each other. Even if you attack and entrap the other, the encounter is not possible. It’s a vicious circle that must be broken.

How can the current climate in Algeria be explained?

I was born in 1979, so I am myself a child of the civil war. In 1997, at the University of Béjaïa, 50 people had their throats slit, systematically. The civil war caused more than 280,000 deaths. How would you begin to build a society that has lived through this? The Algerian people are capable of the worst as well as the best. They are capable of generosity as well as extraordinary violence. It is a schizophrenic country.

Algeria is quite proud of its oil reserves and of its currency, but does not even bother to provide housing and jobs for its citizens. A young man who has no job, how can he take a girl out for a drink, and where? Young people can’t meet each other and can’t love each other; this creates frustration. An average rent today in Algiers is $25,000, and you have to pay one year or two years in advance to be able to move in.

The Algerian people are capable of the worst as well as the best. They are capable of generosity as well as extraordinary violence. It is a schizophrenic country.

How can the country get out of the deadlock you describe?

First and foremost, society must take charge. There is so much incompetence in this country. Quite often there are great initiatives, but society is one of such disorganisation that everything ends in collapse. The first thing that needs to be addressed is the education system, which is educating intellectual terrorists. I believe in an intellectual revolution and I think we must provoke it. We have no elites in this country anymore, except those wasting away in the bars; it’s an elite that feels abused and depressed. If we don’t undertake this intellectual revolution, a revolution of the educational system, we are doomed to remain a fragmented, divided society.

We have here the first independent press of the Arab world, with 250 dailies, but this is not enough because the press remains an instrument of the government. The history of Algeria is limited to extreme nationalism and male chauvinism. We have completely refused to build a nation. Even the history of our independence has been stolen from us: We are hostage to the story told by the FLN and by the regime in power.

We have here the first independent press of the Arab world, with 250 dailies.

Reconquering the public space remains an important issue in Algeria. For now, we do not have the right to demonstrate even though the curfew is officially over — unless you want the cops to come and get rid of everyone. In the film there is a scene in the police station where we see the portrait of Bouteflika fall from its high place on the wall. A totalitarian, completely despotic system like that cannot continue. One day someone will arrive who is enlightened enough to understand that we must take back our country.

And what is the role of cinema in all this?

The issues discussed in cinema are central. First and foremost, cinema exists to recreate images. I believe in documentaries, or documentary-style fiction. The Algerian people have to see themselves. It’s healthy, it’s necessary to see oneself. We also need to have opposition. Everyone must make a film, so that the images can be compared, so that there is a real debate, a meeting, a confrontation. If you don’t like an image it’s up to you to give us another.

The first thing that needs to be addressed is the education system, which is educating intellectual terrorists.

The problem in Algeria is that there are no basic rules for cinema. There are no institutions, no distributors, no film schools. One could not speak of an Algerian film industry. The only cinema that really exists is the cinema run by the government, which is shown on television. In Algeria there are 5 to 6 films a year. We even had the presumption to talk about a “New Wave” of Algerian cinema, but there can’t be a New Wave if there is an ideological confrontation. The film festival in Béjaïa refused to accept Gently One Saturday Morning in Film Encounters of Béjaïa, which has always claimed to be a meeting space between filmmakers and the public, and not a place for competition.

“My film has a very Algerian energy about it and I made some very specific choices in Algiers that is full of inside references for the people of Algiers.”

Have Algerian people been able to see your film?

No, and that is one of the difficulties of the film: that the Algerian public cannot see it. Even though the message of the film, the transparency, is addressed to all of us, this is also a story very specific to the Algerian people. My film has a very Algerian energy about it and I made some very specific choices in Algiers that is full of inside references for the people of Algiers. At one point in the film, for example, we see a bridge that is well known as the “suicide bridge”. So many young people were killing themselves on the bridge that the city had to install gates.

Do you have any other projects in the pipeline?

I have a documentary about a group of stonemasons who play rock chaoui [a genre of Algerian music] in a village in the region of Aurès, where the first bomb in the war for independence went off. And I also hope to start writing fiction again.

Translated from French by Adam Dexter, edited by Helen Southcott and Aidan McMahon.

4 thoughts on “Algerian stampede”

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

mourad tahouri msila alger